Black British people

Distribution by local authorities in the 2011 census | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

Northern Ireland: 11,032 – 0.6% (2021)[4] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English (British English, Black British English, Caribbean English, African English), Creole languages, French, Jamaican Patois, Nigerian Pidgin, and other languages | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity (66.9%); minority follows Islam (17.3%), other faiths (0.8%)[b] or are irreligious (8.6%) 2021 census, NI, England and Wales only[5][6] |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

Black British people or Black Britons[7] are a multi-ethnic group of British people of Sub-Saharan African or Afro-Caribbean descent.[8] The term Black British developed during the 1960s,[9] referring to Black British people from the former British West Indies (sometimes called the Windrush Generation), and from Africa.

The term black has historically had a number of applications as a racial and political label. It may also be used in a wider sociopolitical context to encompass a broader range of non-European ethnic minority populations in Britain, though this usage has become less common over time.[10] Black British is one of several self-designation entries used in official UK ethnicity classifications.

Around 3.7 per cent of the United Kingdom's population in 2021 were Black. The figures have increased from the 1991 census when 1.63 per cent of the population were recorded as Black or Black British to 1.15 million residents in 2001, or 2 per cent of the population, this further increased to just over 1.9 million in 2011, representing 3 per cent. Almost 96 per cent of Black Britons live in England, particularly in England's larger urban areas, with close to 1.2 million living in Greater London.

Terminology

The term Black British has most commonly been used to refer to Black people from the Commonwealth of Nations, of both West African and South Asian descent. For example, Southall Black Sisters was established in 1979 "to meet the needs of black (Asian and Afro-Caribbean) women".[11] Note that "Asian" in the British context usually refers to people of South Asian ancestry.[12][13] Black was used in this inclusive political sense to mean "non-white British".[14]

In the 1970s, a time of rising activism against racial discrimination, the main communities described as Black were from the British West Indies and the Indian subcontinent. Solidarity against racism and discrimination sometimes extended the term at that time to the Irish community in Britain as well.[15][16]

Several organisations continue to use the term inclusively, such as the Black Arts Alliance,[17][18] who extend their use of the term to Latin Americans and all refugees,[19] and the National Black Police Association.[20] The official UK Census has separate self-designation entries for respondents to identify as "Asian British", "Black British" and "Other ethnic group".[2] Due to the Indian diaspora and in particular Idi Amin's expulsion of Asians from Uganda in 1972, many British Asians are from families that had previously lived for several generations in the British West Indies or the Comoros.[21] A number of British Asians, including celebrities such as Riz Ahmed and Zayn Malik, still use the term "Black" and "Asian" interchangeably.[22]

Census classification

The 1991 UK census was the first to include a question on ethnicity. As of the 2011 UK Census, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) allow people in England and Wales and Northern Ireland who self-identify as "Black" to select "Black African", "Black Caribbean" or "Any other Black/African/Caribbean background" tick boxes.[2] For the 2011 Scottish census, the General Register Office for Scotland (GOS) also established new, separate "African, African Scottish or African British" and "Caribbean, Caribbean Scottish or Caribbean British" tick boxes for individuals in Scotland from Africa and the Caribbean, respectively, who do not identify as "Black, Black Scottish or Black British".[23] The 2021 census in England and Wales maintained the Caribbean, African, and any other Black, Black British, or Caribbean background options, adding a write-in response for the 'Black African' group. In Northern Ireland, the 2021 census had Black African and Black Other tick-boxes. In Scotland, the options were African, Scottish African or British African, and Caribbean or Black, each accompanied by a write-in response box.[24]

In all of the UK censuses, persons with multiple familial ancestries can write in their respective ethnicities under a "Mixed or multiple ethnic groups" option, which includes additional "White and Black Caribbean" or "White and Black African" tick boxes in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland.[2]

Historical usage

Black British or Black English was also a term for those Black and mixed-race people in Sierra Leone (known as the Creoles or the Krio(s)) who were descendants of migrants from England and Canada and identified as British.[25] They are generally the descendants of black people who lived in England in the 18th century and freed Black American slaves who fought for the Crown in the American Revolutionary War (see also Black Loyalists). In 1787, hundreds of London's black poor (a category that included the East Indian seamen known as lascars) agreed to go to this West African colony on the condition that they would retain the status of British subjects, live in freedom under the protection of the British Crown, and be defended by the Royal Navy. Making this fresh start with them were some white people (see also Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor), including lovers, wives, and widows of the black men.[26] In addition, nearly 1200 Black Loyalists, former American slaves who had been freed and resettled in Nova Scotia, and 550 Jamaican Maroons also chose to join the new colony.[27][28]

History

Antiquity

According to the Augustan History, North African Roman emperor Septimus Severus supposedly visited Hadrian's Wall in 210 AD. While returning from an inspection of the wall, he was said to have been mocked by an Ethiopian soldier holding a garland of cypress-boughs. Severus ordered him away, reportedly being "frightened"[29] by his dark skin colour[29][30][31] and seeing his act and appearance as an omen. The Ethiopian is written to have said: "You have been all things, you have conquered all things, now, O conqueror, be a god."[32][33]

Anglo-Saxon England

A girl buried at Updown, near Eastry in Kent in the early 7th century was found to have 33% of her DNA of West African type, most closely resembling Esan or Yoruba groups.[34]

In 2013,[35][36] a skeleton was discovered in Fairford, Gloucestershire, which forensic anthropology revealed to be that of a Sub-Saharan African woman. Her remains have been dated between the years 896 and 1025.[36] Local historians believe she was likely either a slave or a bonded servant.[37]

16th century

A black musician is among the six trumpeters depicted in the royal retinue of Henry VIII in the Westminster Tournament Roll, an illuminated manuscript dating from 1511. He wears the royal livery and is mounted on horseback. The man is generally identified as the "John Blanke, the blacke trumpeter," who is listed in the payment accounts of both Henry VIII and his father, Henry VII.[38][39] A group of Africans at the court of James IV of Scotland, included Ellen More and a drummer referred to as the "More taubronar". Both he and John Blanke were paid wages for their services.[40] A small number of black Africans worked as independent business owners in London in the late 1500s, including the silk weaver Reasonable Blackman.[41][42][43]

When trade lines began to open between London and West Africa, persons from this area began coming to Britain on board merchant and slaving ships. For example, merchant John Lok brought several captives to London in 1555 from Guinea. The voyage account in Hakluyt reports that they: "were tall and strong men, and could wel agree with our meates and drinkes. The colde and moyst aire doth somewhat offend them."[44]

During the later 16th century as well as into the first two decades of the 17th century, 25 people named in the records of the small parish of St. Botolph's in Aldgate are identified as "blackamoors."[45] In the period of the war with Spain, between 1588 and 1604, there was an increase in the number of people reaching England from Spanish colonial expeditions in parts of Africa. The English freed many of these captives from enslavement on Spanish ships. They arrived in England largely as a by-product of the slave trade; some were of mixed-race African and Spanish, and became interpreters or sailors.[46] American historian Ira Berlin classified such persons as Atlantic Creoles or the Charter Generation of slaves and multi-racial workers in North America.[47] Slaver John Hawkins arrived in London with 300 captives from West Africa.[46] However, the slave trade did not become entrenched until the 17th century and Hawkins only embarked on three expeditions.

Jacques Francis has been described as a slave by some historians,[48][49][50] but described himself in Latin as a "famulus", meaning servant, slave or attendant.[51][52] Francis was born on an island off the coast of Guinea, likely Arguin Island, off the coast of Mauritania.[53][54][55] He worked as a diver for Pietro Paulo Corsi in his salvage operations on the sunken St Mary and St Edward of Southampton and other ships, such as the Mary Rose, which had sunk in Portsmouth Harbour. When Corsi was accused of theft, Francis stood by him in an English court. With help from an interpreter, he supported his master's claims of innocence. Some of the depositions in the case displayed negative attitudes towards slaves or black people as witnesses.[56] In March 2019 two of the skeletons found on the Mary Rose were found to have Southern European or North African ancestry; one found to be wearing a leather wrist-guard bearing the arms of Catherine of Aragon and royal arms of England is thought to possibly be Spanish or North African, the other, known as "Henry" was thought to also have similar genetic makeup. Henry’s mitochondrial DNA showed that his ancestry may have came from Southern Europe, the Near East, or North Africa, although Dr Sam Robson from the University of Portsmouth "ruled out" that Henry was black or that he was sub-Saharan African in origin. Dr Onyeka Nubia cautioned that the number of those on board the Mary Rose that had heritage beyond Britain was not necessarily representative of the whole of England at the time, although it definitely was not a "one-off".[57] It is thought they are likely to have travelled through Spain or Portugal before arriving in Britain.[57]

Blackamoor servants were perceived as a fashionable novelty and worked in the households of several prominent Elizabethans, including that of Queen Elizabeth I, William Pole, Francis Drake,[58][59][46] and Anne of Denmark in Scotland.[60] Among these servants was "John Come-quick, a blackemore", servant to Capt Thomas Love.[46] Others included in parish registers include Domingo "a black neigro servaunt unto Sir William Winter", buried the xxviith daye of August [1587] and "Frauncis a Blackamoor servant to Thomas Parker", buried in January 1591.[61] Some were free workers, although most were employed as domestic servants and entertainers. Some worked in ports, but were invariably described as chattel labour.[62]

The African population may have been several hundred during the Elizabethan period, however not all were Sub-Saharan African.[57] Historian Michael Wood noted that Africans in England were "mostly free... [and] both men and women, married native English people."[63] Archival evidence shows records of more than 360 African people between 1500 and 1640 in England and Scotland.[64][65][66] Reacting to the darker complexion of people with biracial parentage, George Best argued in 1578 that black skin was not related to the heat of the sun (in Africa) but was instead caused by biblical damnation. Reginald Scot noted that superstitious people associated black skin with demons and ghosts, writing (in his sceptical book Discoverie of Witchcraft) "But in our childhood our mothers maids have so terrified us with an ouglie divell having hornes on his head, and a taile in his breech, eies like a bason, fanges like a dog, clawes like a beare, a skin like a Niger and a voice roring like a lion"; historian Ian Mortimer stated that such views "are to be noted at all levels of society".[67][68] Views on Black people were "affected by preconceived notions of the Garden of Eden and the Fall from Grace."[66] In addition, in this period, England had no concept of naturalization as a means of incorporating immigrants into the society. It conceived of English subjects as those people born on the island. Those who were not were considered by some to be incapable of becoming subjects or citizens.[69]

In 1596, Queen Elizabeth I issued letters to the lord mayors of major cities asserting that "of late divers blackmoores brought into this realm, of which kind of people there are already here to manie...". While visiting the English court, Casper Van Senden, a German merchant from Lübeck, requested the permission to transport "Blackamoores" living in England to Portugal or Spain, presumably to sell them there. Elizabeth subsequently issued a royal warrant to Van Senden, granting him the right to do so.[70] However, Van Senden and Sherley did not succeed in this effort, as they acknowledged in correspondence with Sir Robert Cecil.[71] In 1601, Elizabeth issued another proclamation expressing that she was "highly discontented to understand the great number of Negroes and blackamoors which (as she is informed) are carried into this realm",[72] and again licensing van Senden to deport them. Her proclamation of 1601 stated that the blackamoors were "fostered and powered here, to the great annoyance of [the queen's] own liege people, that covet the relief, which those people consume". It further stated that "most of them are infidels, having no understanding of Christ or his Gospel".[73][74]

Studies of African people in early modern Britain indicate a minor continuing presence. Such studies include Imtiaz Habib's Black Lives in the English Archives, 1500–1677: Imprints of the Invisible (Ashgate, 2008),[75] Onyeka's Blackamoores: Africans in Tudor England, Their Presence, Status and Origins (Narrative Eye, 2013),[76] Miranda Kaufmann's Oxford DPhil thesis Africans in Britain, 1500–1640,[77] and her Black Tudors: The Untold Story (Oneworld Publications, 2017).[78]

17th and 18th centuries

Slavery and the slave trade

Britain was involved in the tri-continental slave trade between Europe, Africa and the Americas. Many of those involved in British colonial activities, such as ship's captains, colonial officials, merchants, slave traders and plantation owners brought black slaves as servants back to Britain with them. This caused an increasing black presence in the northern, eastern, and southern areas of London. One of the most famous slaves to attend a sea captain was known as Sambo. He fell ill shortly after arriving in England and was consequently buried in Lancashire. His plaque and gravestone still stand to this day. There were also small numbers of free slaves and seamen from West Africa and South Asia. Many of these people were forced into beggary due to the lack of jobs and racial discrimination.[80][81] In 1687, a "Moor" was given the freedom of the city of York. He is listed in the freemen's rolls as "John Moore – blacke". He is the only black person to have been found to date in the York rolls.[82]

The involvement of merchants from Great Britain[83] in the transatlantic slave trade was the most important factor in the development of the Black British community. These communities flourished in port cities strongly involved in the slave trade, such as Liverpool[83] and Bristol. Some Liverpudlians are able to trace their black heritage in the city back ten generations.[83] Early black settlers in the city included seamen, the mixed-race children of traders sent to be educated in England, servants, and freed slaves. Mistaken references to slaves entering the country after 1722 being deemed to be free men are derived from a source in which 1722 is a misprint for 1772, in turn based on a misunderstanding of the results of the Somerset case referred to below.[84][85] As a result, Liverpool is home to Britain's oldest black community, dating at least to the 1730s. By 1795, Liverpool had 62.5 per cent of the European Slave Trade.[83]

During this era, Lord Mansfield declared that a slave who fled from his master could not be taken by force in England, nor sold abroad. However, Mansfield was at pains to point out that his ruling did not comment on the legality of slavery itself.[86] This verdict fueled the numbers of Blacks who escaped slavery, and helped send slavery into decline. During this same period, many former American slave soldiers, who had fought on the side of the British in the American Revolutionary War, were resettled as free men in London. They were never awarded pensions, and many of them became poverty-stricken and were reduced to begging on the streets. Reports at the time stated that they "had no prospect of subsisting in this country but by depredations on the public, or by common charity". A sympathetic observer wrote that "great numbers of Blacks and People of Colour, many of them refugees from America and others who have by land or sea been in his Majesty's service were... in great distress." Even towards white loyalists there was little good will to new arrivals from America.[87]

Officially, slavery was not legal in England.[88] The Cartwright decision of 1569 resolved that England was "too pure an air for a slave to breathe in". However, black African slaves continued to be bought and sold in England during the eighteenth century.[89] The slavery issue was not legally contested until the Somerset case of 1772, which concerned James Somersett, a fugitive black slave from Virginia. Lord Chief Justice William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield concluded that Somerset could not be forced to leave England against his will. He later reiterated: "The determinations go no further than that the master cannot by force compel him to go out of the kingdom."[90] Despite the previous rulings, such as the 1706 declaration (which was clarified a year later) by Lord Chief Justice Holt[91] on slavery not being legal in Britain, it was often ignored, with slaveowners arguing that the slaves were property and therefore could not be considered people.[92] Slave owner Thomas Papillon was one of many who took his black servant "to be in the nature and quality of my goods and chattel".[93][94]

Rise in population

Black people lived among whites in London in areas of Mile End, Stepney, Paddington, and St Giles. After Mansfield's ruling many former slaves continued to work for their old masters as paid employees. Between 14,000 and 15,000 (then contemporary estimates) slaves were immediately freed in England.[95] Many of these emancipated individuals became labelled as the "black poor", the black poor were defined as former slave soldiers since emancipated, seafarers, such as South Asian lascars,[96] former indentured servants and former indentured plantation workers.[97] Around the 1750s, London became the home to many Blacks, as well as Jews, Irish, Germans and Huguenots. According to Gretchen Gerzina in her Black London, by the mid-18th century, Blacks accounted for somewhere between 1% and 3% of the London populace.[98][99] Evidence of the number of Black residents in the city has been found through registered burials. Some black people in London resisted slavery through escape.[98] Leading Black activists of this era included Olaudah Equiano, Ignatius Sancho and Quobna Ottobah Cugoano. Mixed race Dido Elizabeth Belle who was born a slave in the Caribbean moved to Britain with her white father in the 1760s. In 1764, The Gentleman's Magazine reported that there was "supposed to be near 20,000 Negroe servants."[100]

John Ystumllyn (c. 1738 - 1786) was the first well-recorded black person of North Wales. He may have been a victim of the Atlantic slave trade, and was from either West Africa or the West Indies. He was taken by the Wynn family to their Ystumllyn estate in Criccieth, and christened with the Welsh name John Ystumllyn. He was taught English and Welsh by the locals, became a gardener at the estate and "grew into a handsome and vigorous young man". His portrait was painted in 1750s. He married local woman Margaret Gruffydd in 1768 and their descendants still live in the area.[101]

It was reported in the Morning Gazette that there was 30,000 in the country as a whole, though the numbers were thought to be "alarmist" exaggerations. In the same year, a party for black men and women in a Fleet Street pub was sufficiently unusual to be written about in the newspapers. Their presence in the country was striking enough to start heated outbreaks of distaste for colonies of Hottentots.[102] Modern historians estimate, based on parish lists, baptismal and marriage registers as well as criminal and sales contracts, that about 10,000 black people lived in Britain during the 18th century.[103][104][93][105] Other estimates put the number at 15,000.[106][107][108]

In 1772, Lord Mansfield put the number of black people in the country at as many as 15,000, though most modern historians consider 10,000 to be the most likely.[93][111] The black population was estimated at around 10,000 in London, making black people approximately 1% of the overall London population. The black population constituted around 0.1% of the total population of Britain in 1780.[112][113] The black female population is estimated to have barely reached 20% of the overall Afro-Caribbean population in the country.[113] In the 1780s with the end of the American Revolutionary War, hundreds of black loyalists from America were resettled in Britain.[114] Marcus Thomas is thought to have been brought at that time from Jamaica as a young boy by the Stanhope family, working as a servant in their home, being baptised age 19, and later joining the Westminster Militia as a drummer.[109][110] Later some emigrated to Sierra Leone, with help from Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor after suffering destitution, to form the Sierra Leone Creole ethnic identity.[115][116][117]

Discrimination

In 1731 the Lord Mayor of London ruled that "no Negroes shall be bound apprentices to any Tradesman or Artificer of this City". Due to this ruling, most were forced into working as domestic servants and other menial professions.[118][93] Those black Londoners who were unpaid servants were in effect slaves in anything but name.[119] In 1787, Thomas Clarkson, an English abolitionist, noted at a speech in Manchester: "I was surprised also to find a great crowd of black people standing round the pulpit. There might be forty or fifty of them."[120] There is evidence that black men and women were occasionally discriminated against when dealing with the law because of their skin colour. In 1737, George Scipio was accused of stealing Anne Godfrey's washing, the case rested entirely on whether or not Scipio was the only black man in Hackney at the time.[121] Ignatius Sancho, black writer, composer, shopkeeper and voter in Westminster wrote, that despite being in Britain since the age of two he felt he was "only a lodger, and hardly that."[122] Sancho complained of "the national antipathy and prejudice" of native white Britons "towards their wooly headed brethren."[123] Sancho was frustrated that many resorted to stereotyping their black neighbours.[124] A financially independent householder, he became the first black person of African origin to vote in parliamentary elections in Britain, in a time when only 3% of the British population were allowed to vote.[125]

Sailors of African descent experienced far less prejudice compared to blacks in the cities such as London. Black sailors would have shared the same quarters, duties and pay as their white shipmates. There are some disputes in the estimation of black sailors, conservative estimates put it between 6% and 8% of navy sailors of the time, this proportion is considerably larger than the population as a whole. Notable examples are Olaudah Equiano and Francis Barber.[126]

Abolitionism

With the support of other Britons, these activists demanded that Blacks be freed from slavery. Supporters involved in these movements included workers and other nationalities of the urban poor. Black people in London who were supporters of the abolitionist movement include Cugoano and Equiano. At this time, slavery in Britain itself had no support from common law, but its definitive legal status was not clearly defined until the 19th century.[citation needed]

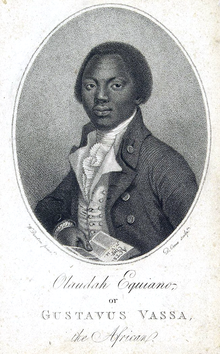

Olaudah Equiano

During the late 18th century, numerous publications and memoirs were written about the "black poor". One example is the writings of Olaudah Equiano, a former slave who wrote a memoir titled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano.

In 1786, Equiano became the first black person to be employed by the British government, when he was made Commissary of Provisions and Stores for the 350 black people suffering from poverty who had decided to accept the government's offer of an assisted passage to Sierra Leone.[127] The following year, in 1787, encouraged by the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor, about 400[128] black Londoners were aided in emigrating to Sierra Leone in West Africa, founding the first British colony on the continent.[129] They asked that their status as British subjects be recognized, along with requests that they be given military protection by the Royal Navy.[130] However, even though the committee signed up about 700 members of the Black Poor, only 441 boarded the three ships that set sail from London to Portsmouth.[131] Many black Londoners were no longer interested in the scheme, and the coercion employed by the committee and the government to recruit them only reinforced their opposition. Equiano, who was originally involved in the scheme, became one of its most vocal critics. Another prominent black Londoner, Ottobah Cugoano, also criticised the scheme.[132][133][134]

Ancestry

In 2007, scientists found the rare paternal haplogroup A1 in a few living British men with Yorkshire surnames. This clade is today almost exclusively found among males in West Africa, where it is also rare. The haplogroup is thought to have been brought to Britain either through enlisted soldiers during Roman Britain, or much later via the modern slave trade. Turi King, a co-author on the study, noted the most probable "guess" was the West African slave trade. Some of the known individuals who arrived through the slave route, such as Ignatius Sancho and Olaudah Equiano, attained a very high social rank. Some married into the general population.[135]

19th century

In the late 18th century, the British slave trade declined in response to changing popular opinion. Both Great Britain and the United States abolished the Atlantic slave trade in 1808, and cooperated in liberating slaves from illegal trading ships off the coast of West Africa. Many of these freed slaves were taken to Sierra Leone for settlement. Slavery was abolished completely in the British Empire by 1834, although it had been profitable on Caribbean plantations. Fewer blacks were brought into London from the West Indies and West Africa.[97] The resident British black population, primarily male, was no longer growing from the trickle of slaves and servants from the West Indies and America.[136]

Abolition meant a virtual halt to the arrival of black people to Britain, just as immigration from Europe was increasing.[137] The black population of Victorian Britain was so small that those living outside of larger trading ports were isolated from the black population.[138][139] The mentioning of black people and descendants in parish registers declined markedly in the early 19th century. It is possible that researchers simply did not collect the data or that the mostly black male population of the late 18th century had married white women.[140][138] Evidence of such marriages may still be found today with descendants of black servants such as Francis Barber, a Jamaican-born servant who lived in Britain during the 18th century. His descendants still live in England today and are white.[118] Abolition of slavery in 1833, effectively ended the period of small-scale black immigration to London and Britain. Though, there were some exceptions, black and Chinese seamen began putting down the roots of small communities in British ports, not least because they were abandoned there by their employers.[137]

By the late 19th century, race discrimination was furthered by theories of scientific racism, which held that whites were the superior race and that blacks were less intelligent than whites. Attempts to support these theories cited "scientific evidence", such as brain size. James Hunt, President of the London Anthropological Society, in 1863 in his paper "On the Negro's place in nature" wrote that "the Negro is inferior intellectually to the European...[and] can only be humanised and civilised by Europeans."[141] In the 1880s, there was a build-up of small groups of black dockside communities in towns such as Canning Town,[142] Liverpool and Cardiff.

Despite social prejudice and discrimination in Victorian England, some 19th-century black Britons achieved exceptional success. Pablo Fanque, born poor as William Darby in Norwich, rose to become the proprietor of one of Britain's most successful Victorian circuses. He is immortalised in the lyrics of The Beatles song "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!" Thirty years after his 1871 death, the chaplain of the Showman's Guild said:

"In the great brotherhood of the equestrian world there is no colour line [bar], for, although Pablo Fanque was of African extraction, he speedily made his way to the top of his profession. The camaraderie of the ring has but one test – ability."[143]

Another great circus performer was equestrian Joseph Hillier, who took over and ran Andrew Ducrow's circus company after Ducrow died.[144]

From the early part of the century, students of African descent were admitted to British Universities. One such student, for example, was the African American James McCune Smith, who travelled from New York City to Glasgow University to study medicine. In 1837 he was awarded a medical doctorate and published two scientific articles in the London Medical Gazette. These articles are the first known to be published by an African-American medical doctor in a scientific journal.[145]

An Indian Briton, Dadabhai Naoroji, stood for election to parliament for the Liberal Party in 1886. He was defeated, leading the leader of the Conservative Party, Lord Salisbury to remark that "however great the progress of mankind has been, and however far we have advanced in overcoming prejudices, I doubt if we have yet got to the point of view where a British constituency would elect a Blackman".[146] Naoroji was elected to parliament in 1892, becoming the second Member of Parliament (MP) of Indian descent after David Ochterlony Dyce Sombre.

20th century

Early 20th century

According to the Sierra Leone Creole barrister and writer, Augustus Merriman-Labor, in his 1909 book Britons Through Negro Spectacles, London's Black population at the time did "not much exceed one hundred" people and "To every one [Black person in London], there are over sixty thousand whites".[147]

World War I saw a small growth in the size of London's Black communities with the arrival of merchant seamen and soldiers. At that time, there were also small groups of students from Africa and the Caribbean migrating into London. These communities are now among the oldest black communities of London.[148] The largest Black communities were to be found in the United Kingdom's great port cities: London's East End, Liverpool, Bristol and Cardiff's Tiger Bay, with other communities in South Shields in Tyne & Wear and Glasgow. In 1914, the black population was estimated at 10,000 and centred largely in London.[149][150]

By 1918 there may have been as many as 20,000[151] or 30,000[149] black people living in Britain. However, the black population was much smaller relative to the total British population of 45 million and official documents were not adapted to record ethnicity.[152] Black residents had for the most part emigrated from parts of the British Empire. The number of black soldiers serving in the British army, (rather than colonial regiments,) prior to World War I is unknown but was likely to have been negligibly low.[150] One of the Black British soldiers during World War I was Walter Tull, an English professional footballer, born to a Barbadian carpenter Daniel Tull and Kent-born Alice Elizabeth Palmer. His grandfather was a slave in Barbados.[153] Tull became the first British-born mixed-heritage infantry officer in a regular British Army regiment, despite the 1914 Manual of Military Law specifically excluding soldiers that were not "of pure European descent" from becoming commissioned officers.[154][155][156]

Colonial soldiers and sailors of Afro-Caribbean descent served in the United Kingdom during the First World War and some settled in British cities. The South Shields community—which also included other "coloured" seamen known as lascars, who were from South Asia and the Arab world—were victims of the UK's first race riot in 1919.[157] Soon eight other cities with significant non-white communities were also hit by race riots.[158] Due to these disturbances, many of the residents from the Arab world as well as some other immigrants were evacuated to their homelands.[159] In that first postwar summer, other racial riots of whites against "coloured" peoples also took place in numerous United States cities, towns in the Caribbean, and South Africa.[158] They were part of the social dislocation after the war as societies struggled to integrate veterans into the work forces again, and groups competed for jobs and housing. At Australian insistence, the British refused to accept the Racial Equality Proposal put forward by the Japanese at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919.

World War II

World War II marked another period of growth for the Black communities in London, Liverpool and elsewhere in Britain. Many Blacks from the Caribbean and West Africa arrived in small groups as wartime workers, merchant seamen, and servicemen from the army, navy, and air forces.[160] For example, in February 1941, 345 West Indians came to work in factories in and around Liverpool, making munitions.[161] Among those from the Caribbean who joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) and gave distinguished service are Ulric Cross[162] from Trinidad, Cy Grant[163] from Guyana and Billy Strachan[164] from Jamaica. The African and Caribbean War Memorial was installed in Brixton, London, in 2017 by the Nubian Jak Community Trust to honour servicemen from Africa and the Caribbean who served alongside British and Commonwealth Forces in both the First World War and Second World War.[165]

By the end of 1943, there were 3,312 African-American GIs based at Maghull and Huyton, near Liverpool.[166] The Black population in the summer of 1944 was estimated at 150,000, mostly Black GIs from the United States. However, by 1948 the Black population was estimated to have been less than 20,000 and did not reach the previous peak of 1944 until 1958.[167]

June 1943

Learie Constantine, a West Indian cricketer, was a welfare officer with the Ministry of Labour when he was refused service at a London hotel. He sued for breach of contract and was awarded damages. This particular example is used by some to illustrate the slow change from racism towards acceptance and equality of all citizens in London.[168] In 1943, Amelia King was refused work by the Essex branch of the Women's Land Army because she was black. The decision was overturned after her cause was taken up by Holborn Trades Council,[169] which led to her MP, Walter Edwards, raising the matter in the House of Commons. She ultimately took a placement in Frith Farm, Wickham, Hampshire and had lodgings with a family in the village.[170]

Post-war

In 1950, there were probably fewer than 20,000 non-White residents in Britain, almost all born overseas.[171] After World War II, the largest influx of Black people occurred, mostly from the British West Indies. More than a quarter of a million West Indians, the overwhelming majority of them from Jamaica, settled in Britain in less than a decade. In 1951, the population of Caribbean and African-born people in Britain was estimated at 20,900.[172] In the mid-1960s, Britain had become the centre of the largest overseas population of West Indians.[173] This migration event is often labelled "Windrush", a reference to the HMT Empire Windrush, the ship that carried the first major group of Caribbean migrants to the United Kingdom in 1948.[174]

"Caribbean" is itself not one ethnic or political identity; for example, some of this wave of immigrants were Indo-Caribbean. The most widely used term used at that time was West Indian (or sometimes coloured). Black British did not come into widespread use until the second generation were born to these post-war migrants to the UK. Although British by nationality, due to friction between them and the White majority they were often born into communities that were relatively closed, creating the roots of what would become a distinct Black British identity. By the 1950s, there was a consciousness of Black people as a separate group that had not been there during 1932–1938.[173] The increasing consciousness of Black British peoples was deeply informed by the influx of Black American culture imported by Black servicemen during and after World War II, music being a central example of what Jacqueline Nassy-Brown calls "diasporic resources". These close interactions between Americans and Black British were not only material but also inspired the expatriation of some Black British women to America after marrying servicemen (some of whom later repatriated to the UK).[175]

Late 20th century

In 1961, the population of people born in Africa or the Caribbean was estimated at 191,600, just under 0.4% of the total UK population.[172] The 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act was passed in Britain along with a succession of other laws in 1968, 1971 and 1981, which severely restricted the entry of Black immigrants into Britain. During this period it is widely argued that emergent blacks and Asians struggled in Britain against racism and prejudice. During the 1970s—and partly in response to both the rise in racial intolerance and the rise of the Black Power movement abroad—black became detached from its negative connotations, and was reclaimed as a marker of pride: black is beautiful.[173] In 1975, David Pitt was appointed to the House of Lords. He spoke against racism and for equality in regards to all residents of Britain. In the years that followed, several Black members were elected into the British Parliament. By 1981, the black population in the United Kingdom was estimated at 1.2% of all countries of birth, being 0.8% Black-Caribbean, 0.3% Black-Other, and 0.1% Black-African residents.[176]

Since the 1980s, the majority of black immigrants into the country have come directly from Africa, in particular, Nigeria and Ghana in West Africa, Uganda and Kenya in East Africa, Zimbabwe, and South Africa in Southern Africa.[citation needed] Nigerians and Ghanaians have been especially quick to accustom themselves to British life, with young Nigerians and Ghanaians achieving some of the best results at GCSE and A-Level, often on a par or above the performance of white pupils.[177] The rate of inter-racial marriage between British citizens born in Africa and native Britons is still fairly low, compared to those from the Caribbean.

By the end of the 20th century the number of black Londoners numbered half a million, according to the 1991 census. The 1991 census was the first to include a question on ethnicity, and the black population of Great Britain (i.e. the United Kingdom excluding Northern Ireland, where the question was not asked) was recorded as 890,727, or 1.6% of the total population. This figure included 499,964 people in the Black-Caribbean category (0.9%), 212,362 in the Black-African category (0.4%) and 178,401 in the Black-Other category (0.3%).[178][179] An increasing number of black Londoners were London- or British-born. Even with this growing population and the first blacks elected to Parliament, many argue that there was still discrimination and a socio-economic imbalance in London among the blacks. In 1992, the number of blacks in Parliament increased to six, and in 1997, they increased their numbers to nine. There are still many problems that black Londoners face; the new global and high-tech information revolution is changing the urban economy and some argue that it is driving up unemployment rates among blacks relative to non-blacks,[97] something, it is argued, that threatens to erode the progress made thus far.[97] By 2001, the Black British population was recorded at 1,148,738 (2.0%) in the 2001 census.[180]

Street conflicts and policing

The late 1950s through to the late 1980s saw a number of mass street conflicts involving young Afro-Caribbean men and British police officers in English cities, mostly as a result of tensions between members of local black communities and whites.

The first major incident occurred in 1958 in Notting Hill, when roaming gangs of between 300 and 400 white youths attacked Afro-Caribbeans and their houses across the neighbourhood, leading to a number of Afro-Caribbean men being left unconscious in the streets.[181] The following year, Antigua-born Kelso Cochrane died after being set upon and stabbed by a gang of white youths while walking home to Notting Hill.

During the 1970s, police forces across England increasingly began to use the Sus law, provoking a sense that young black men were being discriminated against by the police[182] The next newsworthy outbreak of street fighting occurred in 1976 at the Notting Hill Carnival when several hundred police officers and youths became involved in televised fights and scuffles, with stones thrown at police, baton charges and a number of minor injuries and arrests.[183]

The 1980 St Pauls riot in Bristol saw fighting between local youths and police officers, resulting in numerous minor injuries, damage to property and arrests. In London, 1981 brought further conflict, with a perceived racist police force after the death of 13 black youngsters who were attending a birthday party that ended in the devastating New Cross Fire. The fire was viewed by many as a racist massacre[181] and a major political demonstration, known as the Black People's Day of Action was held to protest against the attacks themselves, a perceived rise in racism, and perceived hostility and indifference from the police, politicians and media.[181] Tensions were further inflamed when, in nearby Brixton, police launched operation Swamp 81, a series of mass stop-and-searches of young black men.[181] Anger erupted when up to 500 people were involved in street fighting between the Metropolitan Police and local Afro-Caribbean community, leading to a number of cars and shops being set on fire, stones thrown at police and hundreds of arrests and minor injuries. A similar pattern occurred further north in England that year, in Toxteth, Liverpool, and Chapeltown, Leeds.[184]

Despite the recommendations of the Scarman Report (published in November 1981),[181] relations between black youths and police did not significantly improve and a further wave of nationwide conflicts occurred in Handsworth, Birmingham, in 1985, when the local South Asian community also became involved. Photographer and artist Pogus Caesar extensively documented the riots.[182] Following the police shooting of a black grandmother Cherry Groce in Brixton, and the death of Cynthia Jarrett during a raid on her home in Tottenham, in north London, protests held at the local police stations did not end peacefully and further street battles with the police erupted,[181] the disturbances later spreading to Manchester's Moss Side.[181] The street battles themselves (involving more stone-throwing, the discharge of one firearm, and several fires) led to two fatalities (in the Broadwater Farm riot) and Brixton.

In 1999, following the Macpherson Inquiry into the 1993 killing of Stephen Lawrence, Sir Paul Condon, commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, accepted that his organisation was institutionally racist. Some members of the Black British community were involved in the 2001 Harehills race riot and 2005 Birmingham race riots.

Surveillance of black populations

In the 1950s the British government became concerned about radicalisation within black immigrant communities, and began measures to surveil them at large. For example, in Sheffield, police constables were authorised to "Observe, visit, and report" on the city's black community, with authorisation for the creation of a card index of details such as address and place of employment of the city's then 534 residents.

Documents from the National Archives show that practices continued into the 1960s, with Manchester police creating reports on immigrant communities' "intermixing, miscegenation and illegitimacy", listing numbers of children by race.[185]

Early 21st century

In 2011, following the shooting of a mixed-race man, Mark Duggan, by police in Tottenham, a protest was held at the local police station. The protest ended with an outbreak of fighting between local youths and police officers leading to widespread disturbances across English cities.

Some analysts claimed that black people were disproportionally represented in the 2011 England riots.[186] Research suggests that race relations in Britain deteriorated in the period following the riots and that prejudice towards ethnic minorities increased.[187] Groups such as the EDL and the BNP were said to be exploiting the situation.[188] Racial tensions between blacks and Asians in Birmingham increased after the deaths of three Asian men at the hands of a black youth.[189]

In a Newsnight discussion on 12 August 2011, historian David Starkey blamed black gangster and rap culture, saying that it had influenced youths of all races.[190] Figures showed that 46 percent of people brought before a courtroom for arrests related to the 2011 riots were black.[191]

During the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom the first ten healthcare workers to die from the virus came from Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) backgrounds, prompting the head of the British Medical Association to call on the government to begin investigating if and why minorities are being disproportionally affected.[192] Early statistics found that black and Asian people were being affected worse than white people, with figures showing 35% of COVID-19 patients were non-white,[193] and similar studies in the US had shown a clear racial disparity.[194] The government announced that they will be launching an official inquiry into the disproportionate impact of coronavirus on Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities with Communities Minister Robert Jenrick acknowledging that "There does appear to be a disproportionate impact of the virus on BAME communities in the UK."[195]

A social media campaign in response to the Clap for our Carers campaign, highlighted the role Black and minority health and key workers and asking the public to continue their support after the pandemic gained more than 12 million views online.[196][197][198] 72 per cent of NHS Staff that died from COVID-19 were reported as being from Black & Minority Ethnic groups, far higher than the number of staff from BAME backgrounds working in the NHS, which stood at 44%.[199] Statistics did show that black people were significantly over-represented, but that as the pandemic progressed the disparity in these figures was reducing.[200] Reports discussed a number of complex contributing factors including health and income inequality, social and environmental factors were exacerbating and contributing to the spread of the disease unequally.[201] In April 2020, after his sister's partner died from the virus, Patrick Vernon set up a fundraising initiative called "The Majonzi Fund" which will provide families with access to small financial grants that can be used to access bereavement counselling and organise memorial events and tributes after the social lockdown has been lifted.[202]

After Brexit, EU nationals working in the health and social care sector were replaced by migrants from non-EU countries such as Nigeria.[203][204] About 141,000 people came from Nigeria in 2023.[205]

In 2024, Kemi Badenoch became the first black leader of any major UK political party to lead the Conservative Party.[206]

Demographics

Population

| Region / Country | 2021[208] | 2011[212] | 2001[216] | 1991[219] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| 2,381,724 | 4.22% | 1,846,614 | 3.48% | 1,132,508 | 2.30% | 874,882 | 1.86% | |

| —Greater London | 1,188,370 | 13.50% | 1,088,640 | 13.32% | 782,849 | 10.92% | 535,216 | 8.01% |

| —West Midlands | 269,019 | 4.52% | 182,125 | 3.25% | 104,032 | 1.98% | 102,206 | 1.98% |

| —South East | 221,584 | 2.39% | 136,013 | 1.58% | 56,914 | 0.71% | 46,636 | 0.62% |

| —East of England | 184,949 | 2.92% | 117,442 | 2.01% | 48,464 | 0.90% | 42,310 | 0.84% |

| —North West | 173,918 | 2.34% | 97,869 | 1.39% | 41,637 | 0.62% | 47,478 | 0.71% |

| —East Midlands | 129,986 | 2.66% | 81,484 | 1.80% | 39,477 | 0.95% | 38,566 | 0.98% |

| —Yorkshire and the Humber | 117,643 | 2.15% | 80,345 | 1.52% | 34,262 | 0.69% | 36,634 | 0.76% |

| —South West | 69,614 | 1.22% | 49,476 | 0.94% | 20,920 | 0.42% | 21,779 | 0.47% |

| —North East | 26,635 | 1.01% | 13,220 | 0.51% | 3,953 | 0.16% | 4,057 | 0.16% |

| 65,414[α] | 1.20% | 36,178 | 0.68% | 6,247 | 0.12% | 6,353 | 0.13% | |

| 27,554 | 0.89% | 18,276 | 0.60% | 7,069 | 0.24% | 9,492 | 0.33% | |

| Northern Ireland | 11,032 | 0.58% | 3,616 | 0.20% | 1,136 | 0.07% | — | — |

| 2,485,724 | 3.71% | 1,905,506 | 3.02% | 1,148,738 | 1.95% | 890,727[β] | 1.62% | |

2021 census

In the 2021 Census, 2,409,278 people in England and Wales were recorded as having Black, Black British, Black Welsh, Caribbean or African ethnicity, accounting for 4.0% of the population.[222] In Northern Ireland, 11,032, or 0.6% of the population, identified as Black African or Black Other.[4] The census in Scotland was delayed for a year and took place in 2022, the equivalent figure was 65,414, representing 1.2% of the population.[3] The ten local authorities with the largest proportion of people who identified as Black were all located in London: Lewisham (26.77%), Southwark (25.13%), Lambeth (23.97%), Croydon (22.64%), Barking and Dagenham (21.39%), Hackney (21.09%), Greenwich (20.96%), Enfield (18.34%), Haringey (17.58%) and Brent (17.51%). Outside of London, Manchester had the largest proportion at 11.94%. In Scotland, the highest proportion was in Aberdeen at 4.20%; in Wales, the highest concentration was in Cardiff at 3.84%; and in Northern Ireland, the highest concentration was in Belfast at 1.34%.[223]

2011 census

The 2011 UK Census recorded 1,904,684 residents who identified as "Black/African/Caribbean/Black British", accounting for 3 per cent of the total UK population.[224] This was the first UK census where the number of self-reported Black African residents exceeded that of Black Caribbeans.[225]

Within England and Wales, 989,628 individuals specified their ethnicity as "Black African", 594,825 as "Black Caribbean", and 280,437 as "Other Black".[226] In Northern Ireland, 2,345 individuals self-reported as "Black African", 372 as "Black Caribbean", and 899 as "Other Black", totaling 3,616 "Black" residents.[227] In Scotland, 29,638 persons identified themselves as "African", choosing either the "African, African Scottish or African British" tick box or the "Other African" tick box and write-in area. 6,540 individuals also self-reported as "Caribbean or Black", selecting either the "Caribbean, Caribbean Scottish or Caribbean British" tick box, the "Black, Black Scottish or Black British" tick box, or the "Other Caribbean or Black" tick box and write-in area.[228] In order to compare UK-wide results, the Office for National Statistics combined the "African" and "Caribbean or Black" entries at the top-level,[2] and reported a total of 36,178 "Black" residents in Scotland.[224] According to the ONS, individuals in Scotland with "Other African", "White" and "Asian" ethnicities as well as "Black" identities could thus all potentially be captured within this combined output.[2] The General Register Office for Scotland, which devised the categories and administers the Scotland census, does not combine the "African" and "Caribbean or Black" entries, maintaining them as separate for individuals who do not self-identify as "Black" (see census classification).[23]

2001 census

In the 2001 Census, 575,876 people in the United Kingdom had reported their ethnicity as "Black Caribbean", 485,277 as "Black African", and 97,585 as "Black Other", making a total of 1,148,738 "Black or Black British" residents. This was equivalent to 2 per cent of the UK population at the time.[180]

Population distribution

Most Black Britons can be found in the large cities and metropolitan areas of the country. The 2011 census found that 1.85 million of a total Black population of 1.9 million lived in England, with 1.09 million of those in London, where they made up 13.3 per cent of the population, compared to 3.5 per cent of England's population and 3 per cent of the UK's population. The ten local authorities with the highest proportion of their populations describing themselves as Black in the census were all in London: Lewisham (27.2 per cent), Southwark (26.9 per cent), Lambeth (25.9 per cent), Hackney (23.1 per cent), Croydon (20.2 per cent), Barking and Dagenham (20.0 per cent), Newham (19.6 per cent), Greenwich (19.1 per cent), Haringey (18.8 per cent) and Brent (18.8 per cent).[224] More specifically, for Black Africans the highest local authority was Southwark (16.4 per cent) followed by Barking and Dagenham (15.4 per cent) and Greenwich (13.8 per cent), whereas for Black Caribbeans the highest was Lewisham (11.2 per cent) followed by Lambeth (9.5 per cent) and Croydon (8.6 per cent).[224]

Outside of London, the next largest populations are in Birmingham (125,760, 11%) / Coventry (30,723, 9%) / Sandwell (29,779, 8.7%) / Wolverhampton (24,636, 9.3%), Manchester (65,893, 12%), Nottingham (32,215, 10%), Leicester (28,766, 8%), Bristol (27,890, 6%), Leeds (25,893, 5.6%), Sheffield (25,512, 4.6%) and Luton (22,735, 10%).[1]

Religion

| Religion | England and Wales | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011[229] | 2021[230] | |||

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| 1,288,371 | 69.1% | 1,613,753 | 67.0% | |

| 272,015 | 14.6% | 416,327 | 17.3% | |

| No religion | 137,467 | 7.4% | 205,375 | 8.5% |

| 2,809 | 0.2% | 2,336 | 0.1% | |

| 5,474 | 0.3% | 1,919 | 0.08% | |

| 1,611 | 0.09% | 1,632 | 0.07% | |

| 1,431 | 0.08% | 306 | 0.01% | |

| Other religions | 7,099 | 0.4% | 13,413 | 0.6% |

| Not Stated | 148,613 | 8.0% | 154,219 | 6.4% |

| Total | 1,864,890 | 100% | 2,409,280 | 100% |

Mixed marriages

An academic journal article published in 2005, citing sources from 1997 and 2001, estimated that nearly half of British-born African-Caribbean men, a third of British-born African-Caribbean women, and a fifth of African men, have white partners.[231] In 2014, The Economist reported that, according to the Labour Force Survey, 48 per cent of black Caribbean men and 34 per cent of black Caribbean women in couples have partners from a different ethnic group. Moreover, mixed-race children under the age of ten with black Caribbean and white parents outnumber black Caribbean children by two-to-one.[232]

Culture and community

Dialect

Multicultural London English is a variety of the English language spoken by a large number of the Black British population of Afro-Caribbean ancestry.[233] British Black dialect has been influenced by Jamaican Patois owing to the large number of immigrants from Jamaica, but it is also spoken or imitated by those of different ancestry.

British Black speech is also heavily influenced by social class and regional dialect (Cockney, Mancunian, Brummie, Scouse, etc.).

African-born immigrants speak African languages and French as well as English.

Music

Black British music is a long-established and influential part of British music. Its presence in the United Kingdom stretches back to the 18th century, encompassing concert performers such as George Bridgetower and street musicians the likes of Billy Waters. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912) achieved great success as a composer at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Jazz Age also had taken an effect on the generation.[234]

In the late 1970s and 1980s, 2 Tone became popular with the British youth; especially in the West Midlands. A blend of punk, ska and pop made it a favourite among both white and black audiences. Famous bands in the genre include the Selecter, the Specials, the Beat and the Bodysnatchers.

Jungle, dubstep, drum and bass, UK garage and grime music originated in London.

The MOBO Awards recognise performers of "Music of Black Origin".

Black Lives in Music (BLiM) was formed after its founders noticed institutionalised racism in the British entertainment industry. BLiM works for equal opportunities for Black, Asian and ethnically diverse people in the jazz and classical music industry, opportunities that include the chance to learn a musical instrument, attend a music school, pursue a career in music and reach senior levels within the sector without facing discrimination.[235][236][237][238]

Media

The Black community in Britain has a number of significant publications. The leading key publication is The Voice newspaper, founded by Val McCalla in 1982, and Britain's only national Black weekly newspaper. The Voice primarily targets the Caribbean diaspora and has been printed for more than 35 years.[239] Secondly, the Black History Month magazine is a central point of focus which leads the nationwide celebration of Black History, Arts and Culture throughout the UK.[240] Pride Magazine, published since 1991, is the largest monthly magazine that targets black British, mixed-race, African and African-Caribbean women in the United Kingdom. In 2007, The Guardian reported that the magazine had dominated the black women's magazine market for more than 15 years.[241] Keep The Faith magazine is a multi-award-winning Black and minority ethnic community magazine produced quarterly since 2005.[242] Keep The Faith's editorial contributors are some of the most powerful and influential movers and shakers, and successful entrepreneurs within BME communities.

Many major Black British publications are handled through Diverse Media Group,[243] which specialises in helping organisations reach Britain's Black and minority ethnic community through the main media they consume. The senior leadership team is a composite of many CEO and owners from the publications listed above.

Publishing

Among Black-led publishing companies established in the UK are New Beacon Books (co-founded 1966 by John La Rose), Allison and Busby (co-founded 1967 by Margaret Busby), Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications (co-founded 1969 by Jessica Huntley and Eric Huntley), Hansib (founded 1970), Karnak House (founded 1975 by Amon Saba Saakana), Black Ink Collective (founded in 1978), Black Womantalk (founded in 1983), Karnak House (founded by Buzz Johnson), Tamarind Books (founded 1987 by Verna Wilkins), and others.[244][245][246][247] The International Book Fair of Radical Black and Third World Books (1982–1995) was an initiative launched by New Beacon Books, Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications and the Race Today Collective.[248]

Social issues

This section may have misleading content. (November 2023) |

Racism

The wave of black immigrants who arrived in Britain from the Caribbean in the 1950s faced significant amounts of racism. For many Caribbean immigrants, their first experience of discrimination came when trying to find private accommodation. They were generally ineligible for council housing because only people who had been resident in the UK for a minimum of five years qualified for it. At the time, there was no anti-discrimination legislation to prevent landlords from refusing to accept black tenants. A survey undertaken in Birmingham in 1956 found that only 15 of a total of 1,000 white people surveyed would let a room to a black tenant. As a result, many black immigrants were forced to live in slum areas of cities, where the housing was of poor quality and there were problems of crime, violence and prostitution.[249][250] One of the most notorious slum landlords was Peter Rachman, who owned around 100 properties in the Notting Hill area of London. Black tenants typically paid twice the rent of white tenants, and lived in conditions of extreme overcrowding.[249]

Historian Winston James argues that the experience of racism in Britain was a major factor in the development of a shared Caribbean identity amongst black immigrants from a range of different island and class backgrounds.[251]

In the 1970s and 1980s, black people in Britain were the victims of racist violence perpetrated by far-right groups such as the National Front.[252] During this period, it was also common for Black footballers to be subjected to racist chanting from crowd members.[253][254]

Racism in Britain in general, including against black people, is considered to have declined over time. Academic Robert Ford demonstrates that social distance, measured using questions from the British Social Attitudes survey about whether people would mind having an ethnic minority boss or have a close relative marry an ethnic minority spouse, declined over the period 1983–1996. These declines were observed for attitudes towards Black and Asian ethnic minorities. Much of this change in attitudes happened in the 1990s. In the 1980s, opposition to interracial marriage were significant.[255][256] Nonetheless, Ford argues that "Racism and racial discrimination remain a part of everyday life for Britain's ethnic minorities. Black and Asian Britons...are less likely to be employed and are more likely to work in worse jobs, live in worse houses and suffer worse health than White Britons".[255] The University of Maryland's Minorities at Risk (MAR) project noted in 2006 that while African-Caribbeans in the United Kingdom no longer face formal discrimination, they continue to be under-represented in politics, and to face discriminatory barriers in access to housing and in employment practices. The project also notes that the British school system "has been indicted on numerous occasions for racism, and for undermining the self-confidence of black children and maligning the culture of their parents". The MAR profile on African-Caribbeans in the United Kingdom notes "growing 'black on black' violence between people from the Caribbean and immigrants from Africa".[257]

There is concern that murders using knives are given insufficient attention because most victims are black. Martin Hewitt of the Metropolitan Police said, "I do fear sometimes that because the majority of those that are injured or killed are coming from certain communities and very often the black communities in London, it doesn't get the sense of collective outrage that it ought to do and really get everyone to a place where we are all doing everything we can to prevent this from happening. It's an enormous effort on our part. We are putting enormous resources in to try and stem the flow of the violence and having some success at doing that. But collectively we all ought to be looking at this and seeing how we can prevent it."[258][259]

A 2023 University of Cambridge survey which featured the largest sample of Black people in Britain found that 88% had reported racial discrimination at work, 79% believed the police unfairly targeted black people with stop and search powers and 80% definitely or somewhat agreed that racial discrimination was the biggest barrier to academic attainment for young Black students.[260]

Education

Young Nigerians and Ghanaians achieved some of the best results at GCSE and A-Level according to a government report published in 2006, often on a par or above the performance of white pupils.[177] According to Department for Education statistics for the 2021–22 academic year, Black British pupils attained below the national average for academic performance at both A-Level and GCSE level. 12.3% of Black British pupils achieved at least 3 As at A Level[261] and an average score of 48.6 was achieved in Attainment 8 scoring at GCSE level.[262] A disparity exists in academic performance between Black African pupils and Black Caribbean pupils at GCSE level. Black African pupils achieved better results than both white pupils and the national average, with an average score of 50.9 and 54.5% of pupils achieving grade 5 or above in both English and Maths GCSE. Meanwhile, Black Caribbean pupils attained an average score of 41.7 with only 34.6% of pupils attaining grade 5 or above in both English and Maths GCSE.[263]

A 2019 report by Universities UK found that student’s race and ethnicity significantly affect their degree outcomes. According to this report from 2017–18, there was a 13% gap between the likelihood of white students and Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) students graduating with a first or 2:1 degree classification at British universities.[264][265]

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Employment

According to the 2005 TUC report Black workers, jobs and poverty, Black and minority ethnic people (BMEs) were more likely to be unemployed than the White population. The rate of unemployment among the White population was 5%, but among ethnic minority groups it was Bangladeshi 17%, Pakistani 15%, Mixed 15%, Black Britons 13%, Other ethnic 12% and Indian 7%. Of the different ethnic groups studied, Asians had the highest poverty rate of 45% (after housing costs), Black Britons 38% and Chinese/other 32% (compared to a poverty rate of 20% for the White population). However, the report did concede that things were slowly improving.[266]

According to 2012 data compiled by the Office for National Statistics, 50% of young black men from 16-24 demographics were unemployed between Q4 2011 and Q1 2012.[267]

A 2014 study by the Black Training and Enterprise Group (BTEG), funded by Trust for London, explored the views of young Black males in London on why their demographic have a higher unemployment rate than any other group of young people, finding that many young Black men in London believe that racism and negative stereotyping are the main reasons for their high unemployment rate.[268]

In 2021, 67% of Black 16 to 64-year-olds were employed, compared to 76% of White British and 69% of British Asians. The employment rate for Black 16 to 24-year-olds was 31%, compared to 56% of White British and 37% of British Asians.[269] The median hourly pay for Black Britons in 2021 was amongst the lowest out of all ethnicity groups at £12.55, ahead of only British Pakistanis and Bangladeshis.[270] In 2023, the Office for National Statistics published more granular analysis and found that UK-born black employees (£15.18) earned more than UK-born white employees (£14.26) in 2022, while non-UK born black employees earned less (£12.95). Overall, black employees had a median hourly pay of £13.53 in 2022.[271] According to Department for Work and Pensions data for between 2018–2021, 24% of black families were in receipt of income-related benefits, compared to 16% of White British families and 8% of British Chinese and Indian families. Black families were also the most likely ethnicity to be in receipt of housing benefit, council tax reduction, and reside in social housing.[272][273] However, White British families (54%) were the most likely out of all ethnic groups to receive state support with 27% of White British families in receipt of the state pension.[272]

Crime

Both racist crime and gang-related crime continues to affect black communities, so much so that the Metropolitan Police launched Operation Trident to tackle black-on-black crimes. Numerous deaths in police custody of black men has generated a general distrust of police among urban blacks in the UK.[274][275] According to the Metropolitan Police Authority in 2002–03 of the 17 deaths in police custody, 10 were black or Asian – black convicts have a disproportionately higher rate of incarceration than other ethnicities. The government reports[276] The overall number of racist incidents recorded by the police rose by 7 per cent from 49,078 in 2002/03 to 52,694 in 2003/04.

Media representation of young black British people has focused particularly on "gangs" with black members and violent crimes involving black victims and perpetrators.[277] According to a Home Office report,[276] 10 per cent of all murder victims between 2000 and 2004 were black. Of these, 56 per cent were murdered by other black people (with 44 per cent of black people murdered by whites and Asians – making black people disproportionately higher victims of killing by people from other ethnicities). In addition, a Freedom of Information request made by The Daily Telegraph shows internal police data that provides a breakdown of the ethnicity of the 18,091 men and boys who police took action against for a range of offences in London in October 2009. Among those proceeded against for street crimes, 54 per cent were black; for robbery, 59 per cent; and for gun crimes, 67 per cent.[278] According to the Office for National Statistics, 18.4% of homicide suspects in England and Wales from March 2019 to March 2021 were Black.[279]

Black people, who according to government statistics[280] make up 2 per cent of the population, are the principal suspects in 11.7 per cent of murders, i.e. in 252 out of 2163 murders committed 2001/2, 2002/3, and 2003/4.[281] Judging on the basis of prison population, a substantial minority (about 35%) of black criminals in the United Kingdom are not British citizens but foreign nationals.[282] In November 2009, the Home Office published a study that showed that, once other variables had been accounted for, ethnicity was not a significant predictor of offending, anti-social behaviour or drug abuse among young people.[283]

After several high-profile investigations such as that of the murder of Stephen Lawrence, the police have been accused of racism, from both within and outside the service. Cressida Dick, head of the Metropolitan Police's anti-racism unit in 2003, remarked that it was "difficult to imagine a situation where we will say we are no longer institutionally racist".[284] Black people were seven times more likely to be stopped and searched by police compared to white people, according to the Home Office. A separate study said black people were more than nine times more likely to be searched.[285]

In 2010, black Britons accounted for around 2.2% of the general UK population, but made up 15% of the British prison population, which experts say is "a result of decades of racial prejudice in the criminal justice system and an overly punitive approach to penal affairs."[286] This proportion decreased to 12.4% by the end of 2022 even though black Britons now made up around 3–4% of the British population.[287] In the prison environment, Black prisoners are the most likely to be involved in violent incidents. In 2020, Black prisoners were most likely out of all ethnic groups to be assailants (319 incidents for every 1,000 prisoners) or involved in violent incidents with no clear victim or assailant (185 incidents for every 1,000 prisoners).[288] In the same year, 32% of children in prison were Black in contrast to 47% of prisoners aged under 18 being White.[289] The Lammy Review, led by David Lammy MP, provided potential reasons on the disproportionate number of black children in prisons including austerity in public services, lack of diversity in the judiciary, and the school system inadequately serving the black community by failing to identify learning difficulties.[290][291]

Health

For some key health measures, including life expectancy, general mortality and many of the leading causes of death in the UK, black Britons have better outcomes than their white British counterparts. As an example, compared to the white population in England, cancer rates are 4% lower in black people, who are also less likely to die of the disease than whites.[292][293][294] Generally, black people in England and Wales have a significantly lower mortality rate from all-causes than whites.[295][296][297] Black people in England and Wales also have a higher life expectancy at birth than their white counterparts.[298][294] One contributing factor put forward is that white Britons are more likely to smoke and to drink harmful levels of alcohol.[299] In England, 3.6% of white Britons have harmful or dependant drinking behaviours compared to 2.3% of black people.[300] In 2019, 14.4% of whites in England smoked cigarettes, compared to 9.7% of black people.[301]

Black Britons face worse outcomes in some health measurements compared to the rest of the population. Out of all ethnicity groups, black people were the most likely to be overweight or obese, the most likely to be dependant on drugs, as well as the most likely to have common mental disorders. 72% of black people in Britain are overweight or obese compared to 64.5% of White British people[302] and 7.5% of black people are dependant on drugs compared to 3.0% of White British people.[303] 22.5% of black people experienced a common mental disorder (including depression, OCD and life anxiety) in the past week compared to 17.3% of White British people, with this figure rising to 29.3% for black women.[304] Black women are also 3.7 times more likely to die from childbirth than white women in the UK, equating to 34 women per 100,000 giving birth.[305] Racist attitudes towards the pain tolerances of black women have been cited as one reason why this disparity exists.[306] In 2021, black Britons had the highest rate of STIs with a new STI rate of 1702.6 per 100,000 population compared to 373.9 per 100,000 population in the White British population.[307] This is consistent with data since at least 1994, and potential reasons to explain the difference include poor healthy literacy, underlying socioeconomic factors, and racism in healthcare settings.[308] In 2022, the British Medical Journal reported findings from a survey revealing 65% of black people have said that they had experienced prejudice from doctors and other staff in healthcare settings, rising to 75% among black 18-34 year olds.[309] Another survey found that 64% of black people in the UK believe that the NHS provides better care to white people.[310]

During the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom, the black population faced severe disparity in outcomes compared to the white population, with early data between March to April 2020 revealing that black people were four times more likely to die with Covid-19 than white people.[311][312] An inquiry commissioned for the government found that racism contributed to the disproportionate death of black people.[313] As the Covid-19 vaccine began to be distributed, the UK Household Longitudinal Study found that 72% of black people were unlikely or very unlikely to get vaccinated compared to 82% of all people saying they were likely or very likely to get the jab.[314] In March 2021, uptake was 30% lower for the black population aged 50–60 compared to the same age group in the white population. Vaccine hesitancy was driven by unethical health treatments towards black people in the past, with many surveyed citing the Tuskegee Syphilis Study in the United States as an example. Another reason given was the lack of trust in the authorities and the perception that black people were being targeted as guinea pigs for the vaccine which was spurred by misinformation online and some religious organisations.[315] Analysis from the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities found that the increased risk of dying from COVID-19 was mainly due to the increased risk of exposure. Black people were more likely to live in urban areas with higher population densities and levels of deprivation; work in higher risk occupations such as healthcare or transport; and to live with older relatives who themselves are at higher risk due to their age or having other comorbidities such as diabetes and obesity.[316]

Notable black British

This section may contain unverified or indiscriminate information in embedded lists. (December 2022) |

Pre-20th century

Well-known black Britons living before the 20th century include the Chartist William Cuffay; William Davidson, who was executed as a Cato Street conspirator; Olaudah Equiano (also called Gustavus Vassa), a former slave who bought his freedom, moved to England, and settled in Soham, Cambridgeshire, where he married and wrote an autobiography, dying in 1797; Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, pioneer of the slave narrative; and Ignatius Sancho, a grocer who also acquired a reputation as a man of letters.

In 2004, a poll found that people considered the Crimean War heroine Mary Seacole to be the greatest Black Briton.[317] Seacole was born in Jamaica in 1805 to a white father and black mother.[318] A statue of her, designed by Martin Jennings, was unveiled in the grounds of St. Thomas' Hospital opposite the Houses of Parliament in London in June 2016, following a 12-year campaign that raised £500,000 to honour her.[319]

Recognition