Avon Gorge

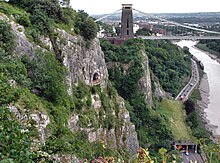

The Avon Gorge (grid reference ST560743) is a 1.5-mile (2.5-kilometre) long gorge on the River Avon in Bristol, England. The gorge runs south to north through a limestone ridge 1.5 miles (2.4 km) west of Bristol city centre, and about 3 miles (5 km) from the mouth of the river at Avonmouth. The gorge forms the boundary between the unitary authorities of North Somerset and Bristol, with the boundary running along the south bank. As Bristol was an important port, the gorge formed a defensive gateway to the city.

On the east of the gorge is the Bristol suburb of Clifton, and The Downs, a large public park. To the west of the gorge is Leigh Woods, the name of both a village and the National Trust forest it is situated in. There are three Iron Age hill forts overlooking the gorge, as well as an observatory. The Clifton Suspension Bridge, an icon of Bristol, crosses the gorge.

51°27′18″N 2°37′40″W / 51.4549°N 2.6279°W

Geology and formation

The gorge cuts through a ridge mainly of limestone, with some sandstone. This particular ridge runs from Clifton to Clevedon, 10 miles (16 km) away on the Bristol Channel coast, although limestone is found throughout the Bristol area. The fossil shells and corals indicate that the limestone formed in shallow tropical seas in the Carboniferous, 350 million years ago.[1] For a long time it was unclear what caused the Avon to cut through the limestone ridge, rather than run southwest through the Ashton Vale towards Weston-super-Mare. However, Bristol was at the southern edge of glaciation during the Anglian ice age, and it has been suggested that ice blocked the river's natural route through Ashton Vale to the west.[2][3] At the Clifton Suspension Bridge the Gorge is more than 700 feet (213 m) wide and 300 feet (91 m) deep.[4]

In the 18th century the gorge was quarried to produce building stone for the city. Stone was taken by boat into the floating harbour. In the 19th century celestine was discovered in Leigh Court estate and the Miles family authorised quarrying. Between 1880 and 1920 Bristol was producing 90% of the world's celestine, but the enterprise did not last long into the 20th century.[5] Bristol Diamonds, brilliant quartz crystals found in geodes in dolomitic conglomerate in the gorge,[6] were popular souvenirs for visitors to the Hotwells spa in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[7] Quarries on the Bristol side of the gorge are now popular with climbers and are a habitat for Peregrine falcons and other wildlife.

Ecology

The steep walls of the gorge support some rare fauna and flora, including species unique to the gorge. There are a total of 24 rare plant species and two unique trees: the Bristol and Wilmotts's whitebeams.[8] Other notable plants include Bristol rock cress,[9] Bristol onion,[9] spiked speedwell,[10] autumn squill[10] and honewort.[11] Because of its steep sides, there are many parts of the gorge on which trees cannot grow, making way for smaller plants. The gorge is also home to rare invertebrate species.[9] The gorge has a microclimate around 1 degree warmer than the surrounding land.[2] The steep south-west facing sides receive the afternoon sunlight, but are partially sheltered from the prevailing winds. When winds come from the Bristol Channel in the north west they may be funnelled into the gorge, creating harsh and wet conditions.

The steep gorge walls make an ideal habitat for peregrine falcons, with a plentiful supply of food nearby in the form of pigeons and gulls. Peregrines have a history of nesting in the gorge, but having become rare in the British Isles they did not breed and were rarely seen in the gorge after the 1930s. In 1990 Peregrines returned to the gorge, and have successfully bred in most of the following years.[2] On warm days a strong uplift forms in the gorge, on which birds of prey soar while hunting. The gorge also houses large populations of Jackdaw and horseshoe bats, both of which find homes in the caves and bridge buttresses.[8]

Due to its geology and ecology, an area of 155.4 hectares (384.0 acres) of the gorge and surrounding woodland has been protected as a biological and geological Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), the original notification taking place in 1952. The site may in future be protected as a Special Area of Conservation under the European Commission Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC).[12] The Leigh Woods side of the gorge is largely owned by the National Trust. The Downs on the city side of the gorge are owned by Bristol City Council and managed as a large public park. The gorge side is protected in partnership with Bristol Zoo, WWF and English Nature.[9] The council's management of the gorge involves balancing the need to protect its ecology with recreational uses such as rock climbing.

Green-flowered helleborine is found on the western side of the gorge, in a wooded area next to the towpath below Leigh Woods.[13] lady orchid was discovered here in 1990, in Nightingale Valley on the west side of the Gorge; there is some doubt as to whether this was a wild plant or an introduction.[14] fly orchid and bee orchid are found in the gorge, along with their hybrid.[15] A single plant of lesser meadow-rue is present in the gorge.[16] Bristol rock-cress occurs here, and at nearby Penpole Point; in the gorge, there are about 3,000 plants on the Bristol side, and about 2,000 below Leigh Woods.[17] Hutchinsia is found on both sides of the gorge.[18] Bloody crane's-bill grows on the Bristol side of the gorge, where it is believed to be native.[19] Little robin occurs on both sides of the gorge.[20] Spiked speedwell grows on both sides of the gorge: the first British record of this plant was from the gorge, in 1641.[21]

History of human use

The gorge area was inhabited at least as early as the Iron Age, probably by the Dobunni tribe. In Leigh Woods above Nightingale Valley, a steep dry valley beside the suspension bridge, is Stokeleigh Camp, one of three Iron Age hill forts in the area.[22] Stokeleigh was occupied from 3BC to 1AD, and was also used in the Middle Ages.[22] The camp was protected on two sides by the cliff faces of the gorge and Nightingale Valley, and was also protected by earthworks, and is now a scheduled ancient monument.[23] A second hill fort was situated across Nightingale Valley, but has since been built on, and bridge road cuts through it. The third hill fort was situated on the opposite side of the gorge, in what is now observatory green. Archaeology, plus the configuration of the three forts, suggest they played a role in defending the gorge.[8]

During the Middle Ages and Industrial Revolution the area which now forms The Downs was used as common grazing land. It was mined for lead, calamine, iron and limestone, and became home to a windmill which produced snuff from the tobacco which had become one of the city's principal imports.[24] In 1777 the windmill burnt out in a storm, and the building was converted into the observatory, which houses a camera obscura.[25] In the 18th and 19th centuries Bristol's economy boomed and Clifton became a desirable place to live. Mansion houses were built overlooking the gorge, but after grazing was stopped, trees grew and obscured the view from these mansions. In the Victorian era, with houses creeping further onto the Downs, an Act of Parliament was passed to protect them as a park for the people of Bristol. In 1754 a bridge to span the gorge was proposed, but it was nearly 80 years before work began on Isambard Kingdom Brunel's Clifton Suspension Bridge, and a further 30 years before it was completed.[26][27] Today the bridge is perhaps the best known landmark in Bristol.

Throughout Bristol's history the gorge has been an important transport route, carrying the River Avon, major roads and two railways. It is the gateway to Bristol Harbour, and provided protection against storms or attack. The Bristol Channel and Avon estuary have a very high tidal range of 15 metres (49 ft),[28] second only to Bay of Fundy in Eastern Canada;[29][30] and the gorge is relatively narrow and meandering, making it notoriously difficult to navigate. Several vessels have grounded in the gorge including the SS Demerara soon after her launch in 1851, the schooner Gipsy in 1878, the steam tug Black Eagle in 1861 and the Llandaff City.[31] The phrase "ship shape and Bristol fashion" arises from when the main harbour in Bristol was tidal, the bottom of which was rocky. If ships were not of stout construction then they would simply break up as the tide receded, hence the phrase.[32]

A railway, the Bristol Port Railway, was built through the gorge on the east side from Hotwells to Avonmouth between 1863 and 1865. The Portishead Railway was opened on the west side in 1867. The section of the Bristol Port Railway between Hotwells and Sneyd Park junction was closed in 1922, when construction of a major road through the gorge, the Portway, was started. The Portway was opened in 1926. The road is now part of the A4 road, linking Bristol city centre to the M5 motorway, which bypasses the city near Avonmouth. In the late 1990s the wide pavement through nearly all the Avon Gorge was designated to be legally usable by both cyclists and the fewer pedestrians.

Two railways still run through the gorge. On the east side the Severn Beach Line to Avonmouth and Severn Beach uses the remaining part of the Bristol Port Railway through part of the gorge, and through a tunnel under the Downs. On the west side the Portishead Railway was closed by the Beeching Axe in the 1960s, but has since been reopened for freight traffic as far as Royal Portbury Dock, 2.5 miles (4 km) downstream,[33] and funding is now in place to reopen the rest of the line and reintroduce passenger services to Portishead.[34][35] Between 1893 and 1934, the Clifton Rocks Railway linked the passenger steamer pier at Hotwells with Clifton on the rim of the gorge.[36]

A footpath and National Cycle Network cycleway run alongside the Portishead Railway and along the old towpath.

The gorge's proximity to the urban population of Bristol made it a popular venue for rock climbing from the 1940s[37] – a time when most UK climbing was centred in mountain areas. The first guide to climbing routes in Avon Gorge was published in 1955 by the University of Bristol Mountaineering Club. The same year, British mountaineer Chris Bonington climbed Main Wall putting up Mercavity.[38] The 2017 edition of The Climbers' Club Guide to Avon Gorge by Martin Crocker[39] lists 400 pages of routes and guidance. Avon Gorge is often criticised as being so over-climbed many of the routes are "polished".[40]

Mythology

The formation of the Avon Gorge is the subject of mediaeval mythology. The myths tell tales of two giant brothers, Goram and Vincent, who constructed the gorge. One variation holds that Vincent and Goram were constructing the gorge together and Goram fell asleep, to be accidentally killed by Vincent's pickaxe. Another variation tells of the brothers falling for Avona, a girl from Wiltshire, who instructs the giants to drain a lake which stretches from Rownham Hill to Bradford-on-Avon (i.e. the Avon valley). Goram began digging the nearby Hazel Brook Gorge in Blaise Castle estate, but consumed too much beer and fell asleep. Vincent dug the Avon Gorge and drained the lake, winning the affection of Avona. Upon waking Goram stamped his foot, creating "The Giant's Footprint" in the Blaise Castle estate, and threw himself into the Bristol Channel, turning to stone and leaving his head and shoulder above water as the islands of Flat Holm and Steep Holm.[41]

References

Notes

- ^ "Geology and biodiversitymaking the links" (PDF). English Nature. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ a b c River Avon Trail, 'Avon Gorge'. Accessed 5 May 2006.

- ^ Haslett, Simon K. (2010). Somerset Landscapes: Geology and landforms. Usk: Blackbarn Books. pp. 108–112. ISBN 978-1-4564-1631-7.

- ^ "Geology". Avon Gorge and Downs. Archived from the original on 18 September 2007. Retrieved 11 September 2008.

- ^ C.G. Down, 1968. "Paradise Bottom." The Industrial Railway Record No. 22 – p352-354

- ^ Savage, Robert J. G. (Spring 1989). "Natural History of the Goldney Garden Grotto, Clifton, Bristol". Garden History. 17 (1). Reading, England: The Garden History Society: 1–40. doi:10.2307/1586914. ISSN 0307-1243. JSTOR 1586914.

- ^ Hutton, Stanley (1907). Bristol and its famous associations. Bristol: J. W. Arrowsmith.

- ^ a b c BBC Bristol, "The Avon Gorge – Bristol's Great Glacier?" Accessed 5 May 2006.

- ^ a b c d Avon Wildlife Trust, "The wildlife and habitats of Avon Archived 12 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine." Accessed 24 March 2009.

- ^ a b Leivers, Mandy. "Discover the wildlife of the Avon Gorge & Downs". Bristol Zoo. Archived from the original on 19 March 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ Myles (2000), page 161

- ^ "Woldlife and Geology". Avon Gorge and Downs. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 11 September 2008.

- ^ Myles (2000) page 249

- ^ Myles (2000) page 251

- ^ Myles (2000) page 252

- ^ Myles (2000) page 68

- ^ Myles (2000), page 101

- ^ Myles (2000), page 102

- ^ Myles (2000), page 155

- ^ Myles (2000), page 156

- ^ Myles (2000), page 186

- ^ a b "Avon Gorge". BBC Bristol — Nature. BBC. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ "Stokeleigh Camp". Pastscape. English Nature. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ "The Downs". Environment — Parks and Open spaces. Bristol City Council. Archived from the original on 7 November 2009. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ^ "The Observatory". Bristol link. Archived from the original on 15 June 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2007.

- ^ Vaughan, Adrian: Isambard Kingdom Brunel — Engineering Knight Errant, John Murray, 1991, ISBN 0-7195-5748-8.

- ^ Beckett (1980). Chapter 6: "Bridges".

- ^ "Severn Estuary Barrage". UK Environment Agency. 31 May 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- ^ Chan, Marjorie A.; Archer, Allen William (2003). Extreme Depositional Environments: Mega End Members in Geologic Time. Boulder, Colorado: Geological Society of America. p. 151. ISBN 0-8137-2370-1.

- ^ "Coast: Bristol Channel". BBC. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- ^ "Wrecks on the River Avon". Bristol Radical History Group. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ^ Ship-shape and Bristol fashion on www.phrases.org.uk (retrieved 20 August 2007)

- ^ Portishead Railway Group, 2006. "History of the Portishead Railway Archived 7 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine." Accessed 15 April 2006

- ^ "Money for Portishead". Railfuture. 17 April 2019.

- ^ Wilson, Kate (26 June 2019). "Plans to reopen Bristol to Portishead railway ready to be submitted and line could open in 2023". Bristol Live.

- ^ "Clifton Rocks Railway — History". Subterranea Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 June 2007. Retrieved 3 June 2007.

- ^ "THE HISTORY OF CLIMBING IN THE AVON GORGE". Climb Bristol. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Bonnington, Chris (1957). "Three Climbs at Avon" (PDF). Climbers Club Journal: 36–37.

- ^ Martin, Crocker. Avon Gorge : the definitive climbers' club guide. [U.K.?]. ISBN 978-0-9572815-4-7. OCLC 1023538943.

- ^ "Gronk – My favourite route at Avon! | Dick's Climbing". www.dicksclimbing.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Eugene Byrne & Simon Gurr, 2002. "Bristol Myths and Legends." Bristol 2008: St Vincent's Rock.

Bibliography

- Beckett, Derrick (1980). Brunel's Britain. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7973-9.

- Hussey, David (2000). Coastal and River Trade in Pre-industrial England: Bristol and its Region 1680–1730. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. ISBN 0-9674826-4-X.

- Myles, Sarah (2000) The Flora of the Bristol Region ISBN 1-874357-18-8

External links

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !