California Community Colleges

| |

| Motto | Empowering community colleges through leadership, advocacy, and support |

|---|---|

| Type | Public community college system |

| Established | 1967 |

| Endowment | US $25 million (planned permanent endowment) |

| Chancellor | Sonya Christian |

Academic staff | 57,711 |

| Students | 1,800,000+ |

| Location | |

| Colleges | 116 accredited colleges |

| Affiliations | State of California |

| Website | California Community Colleges Chancellor's Office |

The California Community Colleges is a postsecondary education system in the U.S. state of California.[1] The system includes the Board of Governors of the California Community Colleges and 73 community college districts. The districts currently operate 116 accredited colleges. The California Community Colleges is the largest system of higher education in the United States, and third largest system of higher education in the world, serving more than 1.8 million students.[2] Despite its plural name, the system is consistently referred to in California law as a singular entity.[1]

Under the California Master Plan for Higher Education, the California Community Colleges is a part of the state's public higher education system, which also includes the University of California system and the California State University system. Like the two other systems, the California Community Colleges system is headed by an executive officer and a governing board. The 17-member Board of Governors sets direction for the system and is in turn appointed by the governor of California. The board appoints the Chancellor, who is the chief executive officer of the system. Locally elected Boards of Trustees work on the district level with Presidents who run the individual college campuses.[3]

History

The junior college movement

During the early 20th century, the movement to establish junior colleges in California was led by Professor Alexis F. Lange, dean of the School of Education at the University of California, Berkeley, and David Starr Jordan, president of Stanford University.[4] Both men shared an ulterior motive for supporting the creation of junior colleges.[4] They entertained the hope that one day junior colleges might be able to take over responsibility for all lower-division college-level courses, allowing universities to focus exclusively on upper-division college-level courses, graduate programs, and research.[4] It was under their influence that both Berkeley and Stanford started to draw a clear dividing line between upper and lower divisions of their undergraduate college programs.[5] (Lange and Jordan's desired endpoint never occurred in California—where universities continue to provide lower-division undergraduate education alongside community colleges—but Quebec's Parent Commission was inspired by the California example to take the idea to its logical conclusion, resulting in the creation of CEGEPs.)

In 1907, Lange worked with state senator Anthony Caminetti to bring about the enactment of the Upward Extension Act, the first state law in the United States to formally authorize the creation of junior colleges.[5] Senator Caminetti represented rural Amador County.[6] As articulated by Caminetti, the original rationales for junior colleges were financial, geographical, and practical.[6] Amador County and other rural counties were hundreds of miles away from the state's only universities of any significance at the time: UC Berkeley, Stanford, and the University of Southern California.[6] Such vast distances imposed a massive financial and logistical burden upon rural students who had to move away to attend college and parents who wished to visit their children while they were away at college.[6] Allowing high schools (especially rural ones) to provide two years of lower-division college-level courses meant that "students could stay at home and save money, and parents could supervise their children until they were more mature".[6]

Under the leadership of Fresno school superintendent Charles L. McLane, Fresno High School was the first high school in the state to take advantage of the Upward Extension Act to establish a "Collegiate Department" in the fall of 1910.[6] McLane's argument to the Fresno County Board of Education resembled Caminetti's argument to the state legislature: namely, there was no institution of higher education within 200 miles (321 km) of Fresno and moving away to attend college was both difficult and expensive for local high school graduates and their parents.[6] (This was a bit of an exaggeration, as both Berkeley and Stanford lie within 200 miles of Fresno, but both universities are still more than 150 miles (241 km) away from Fresno.) Berkeley and Stanford assisted with the selection of a principal and a faculty, and 28 students enrolled in the department that fall.[6] The Collegiate Department of Fresno High School later developed into Fresno City College, which is the oldest community college in California and the second oldest community college in the United States.[6] In 1911, the principal of the Collegiate Department, A.C. Olney, transferred to Santa Barbara High School and there created California's second junior college under the Upward Extension Act.[7]

California soon became the leader of the American junior college movement: "In no other state was the vision of the junior college so vigorously pursued as in California."[8] The United States went from zero junior colleges at the start of the 20th century to nineteen junior colleges by 1915, of which eight were based in California: Azusa, Bakersfield, Fresno, Fullerton, Rocklin, San Diego, Santa Ana, and Santa Barbara.[8]

In 1917, the Upward Extension Act was superseded by the Junior College Act, popularly known as the Ballard Act, which established state and county funding support for junior colleges operated as part of K–12 local school districts.[9] The Ballard Act substituted the term "junior college courses" for what had been previously referred to as "post-high school" or "postgraduate courses", and it authorized school districts to offer such courses in "mechanical and industrial arts, household economy, agriculture, civic education, and commerce".[10]

Junior college districts

In 1921, the state legislature enacted the District Junior College Law, which created a junior college fund for California's share of revenue from the federal Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 and used the revenue to support the formation of junior college districts which would be entirely separate from school districts.[9] The District Junior College Law originated with a bill introduced by Assemblywoman Elizabeth Hughes.[11] The District Junior College Law was the first law in the United States to authorize the creation of junior college districts, and it was also the first law to pioneer the creation of "public institutions of higher education that were controlled by a local electorate rather than by an academic elite".[11] The District Junior College Law became a national model for the creation of community college districts.[12]

However, the District Junior College Law as enacted had two major flaws. First, it failed to supersede the Ballard Act.[9] For the next forty years, California's junior colleges were operated by a confusing hodgepodge of school districts (under the Ballard Act) and junior college districts (under the District Junior College Law).[9] Second, as structured, the new law was heavily inspired by a report of a special committee on education in the 1919 state legislature which had recommended that the state normal schools with their two-year teacher training programs should be reconstituted into four-year state teachers colleges, in which the first two years would be a "junior college program of a general nature open to all".[11] By treating junior college as not much more than a general-purpose lower-division component of a state teachers college, the District Junior College Law tacitly encouraged the state teachers colleges to attempt to seize control of junior colleges in their immediate vicinity.[11] This provision was abolished in 1927 and the junior colleges were eventually separated from the state teachers colleges, but not before takeovers had already occurred at Chico, Fresno, Humboldt, Santa Barbara, San Diego, and San Jose.[11]

In September 1921, Modesto Junior College (the 16th oldest community college in the United States) became the first junior college to be governed by a junior college district.[9] Just eight days later, Riverside Junior College reorganized itself to be governed by a junior college district, and two months later, a junior college district was formed at Sacramento.[12]

Growth and transformation

In 1932, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching was asked by the state legislature and governor to perform a study of California higher education.[13] The foundation's report found that junior colleges were wasting their resources on trying to prepare students for transfer to four-year universities, when only a small percentage actually transferred.[13] Although 79% of junior college students at the time expressed interest in such transfers, the report recommended that 85% of junior college students should be in terminal vocational programs.[13] The report helped legitimize the growth of California junior colleges during the Great Depression in the United States—in that many followed its recommendation to focus on vocational education which immediately boosted graduates' short-term earnings rather than lower-division college courses of less certain long-term value—but, by nudging the junior colleges in that direction, also ended pressure to transform junior colleges into four-year institutions.[13]

From 1933 to 1939, 65 public junior colleges were founded in the United States, of which five were founded in California, and the number of American higher education students attending junior colleges rose from 5% in 1930 to 10% in 1940.[13] California again led the nation in developing career and vocational education programs in its junior colleges, using funding from the federal Smith–Hughes Act.[14] Within California, Pasadena City College was the leader of this movement, with vocational enrollment growing from 4% in 1926 to 67% in 1938.[14]

This shift in junior colleges' institutional focus from preparing students for transfer to universities to providing them with vocational education probably gave rise to the broader term "community college", though the source of the term is not clear.[14] In 1932, the Carnegie Foundation report had referred to junior colleges as "community institutions".[14] William T. Boyce, the acting dean (and eventually, president) of Fullerton Junior College, later claimed to have first suggested the term in 1935 at a meeting of a group of California junior college administrators.[15] The first published mention of the term is thought to be a 1936 article by Byron S. Hollingshead, then the president of Scranton-Keystone Junior College in La Plume, Pennsylvania.[15] A.J. Cloud, president of San Francisco Junior College, responded to a 1940 survey questionnaire by arguing that "the junior college is properly a community college".[15]

The 1944 GI Bill dramatically increased college enrollments, and by 1950 there were 50 junior colleges in California.[citation needed] By 1960 there were 56 districts in California offering junior college courses, and 28 of those districts were not high school districts but were junior college districts formed expressly for the governance of those schools.[citation needed]

The Master Plan for Higher Education

The 1960 Master Plan for Higher Education was a turning point in higher education in California. Under the Master Plan, as implemented through the Donahoe Higher Education Act, the UC and CSU systems were to limit their enrollments, yet an overall goal was to "provide an appropriate place in California public higher education for every student who is willing and able to benefit from attendance", meaning the junior colleges were to fulfill this role. The Master Plan provided that junior colleges would be established within commuting distance of nearly all California residents, which required the founding of twenty-two new colleges on top of the sixty-four colleges already operating as of 1960.[16] The Master Plan also reaffirmed the principle that junior colleges were to be governed by local boards, under the general supervision of the California State Board of Education.[17]

In 1961, the Legislature finally fixed the long-running confusion about whether junior colleges should be operated by K–12 school districts or junior college districts.[18] Assembly Bill 2804 created a process by which all the junior colleges created by school districts under the Ballard Act of 1917 or the earlier Upward Extension Act of 1907 would form junior college districts under the District Junior College Law of 1921 (to become entirely independent of school districts).[18]

Formation of a statewide system

The Master Plan refers only to "junior colleges" and does not use the term "community college." During the 1960s, state senator Walter W. Stiern became increasingly vocal about the fact that the junior colleges were the only segment of California public higher education which had not yet been integrated into a statewide system, and proposed appropriate legislation to fix this.[19] Two studies in 1967 found that the California Department of Education (under the State Board of Education's supervision) was too "weak" to provide proper supervision of the junior colleges.[17]

In 1967, the state legislature with the concurrence of the governor enacted Senate Bill 669, which renamed the junior colleges to community colleges, created the Board of Governors for the California Community Colleges to oversee the community colleges, and formally established the community college district system, requiring all areas of the state to be included within a community college district.[17][20] The Board of Governors formerly took over from the State Board of Education on July 1, 1968.[17] The degree of local control in this system, a side effect of the origins of many colleges within high school districts, can be seen in that 53 of the 73 districts (72%) govern only a single college; only a few districts in major metropolitan areas control more than four colleges. The Legislature also expressly expanded the mission of the community colleges to include vocational degree programs and continuing adult education programs.[21]

In 1990, after Stiern's death two years earlier, the Legislature honored his contribution to the creation of the California Community Colleges by creating a short title based on his name for the relevant part of the California Education Code. Education Code Section 70900.5 provides that "this part shall be known, and may be cited, as the 'Walter Stiern Act.'"[22]

Continued evolution

The Master Plan for Higher Education also banned tuition, as it was based on the ideal that public higher education should be free to students (just like K-12 primary and secondary education). As officially enacted, it states that public higher education "shall be tuition free to all residents." Thus, California residents legally do not pay tuition.

The state has suffered severe budget deficits ever since the enacting of Proposition 13 in 1978, which led to the imposition of per-unit enrollment fees for California residents (equivalent in all but name to tuition) at all community colleges and all CSU and UC campuses to get around the legal ban on tuition. Non-resident and international students, however, do pay tuition, which at community colleges is usually an additional $100 per unit (or credit) on top of the standard enrollment fee. Since no other American state bans tuition in public higher education, this issue is unique to California. In summer 2010, the state's public higher education systems began investigating the possibility of dropping the semantic confusion and switching to the more accurate term, tuition.[23]

Tuition and fees have fluctuated with the state's budget. For much of the 1990s and early 2000s, enrollment fees ranged between $11 and $13 per credit. With the state's budget deficits in the early-to-mid 2000s, fees rose to $18 per unit in 2003, and, by 2004, reached $26 per unit. Fees dropped to $20 per unit, down $6 from January 2007. It was the lowest enrollment fee of any college or university in the United States. On July 28, 2009, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed AB2X (the education trailer bill to the 2009-10 state budget), setting the community college enrollment fee back at $26 per unit, effective for the fall 2009 term. In July 2011, per-unit fees at California's community colleges stood at $36 per unit. In summer 2012, fees were raised to $46 per unit.

Moreno Valley College and Norco College became the 111th and 112th colleges of the CCC system in 2010.[24] Clovis Community College opened as the 113th college in 2015,[25] and Compton College was re-established as the 114th college in 2017.[26][27] In fall 2019, Calbright College was opened as an entirely online, but initially unaccredited, community college.[28][29] The most recent in-person addition to the system is Madera Community College, which was recognized by the Board of Governors as the 116th accredited community college, on July 20, 2020.[30]

The system can add up to 30 bachelor's degree programs a year at any of the colleges under a 2021 state law.[31]

Governance

The system is governed by the Board of Governors which, within the bounds of state law, sets systemwide policy. The 17 Board members, who represent the public, faculty, students, and classified employees, are appointed by the governor of California as directed by Section 71000 of the California Education Code.[32] The Board is also directed by the Education Code to allow local authority and control of the community college districts to the "maximum degree permissible" and AB 1725 in 1974 added a formal consultation process which has resulted in the formation of a Consultation Council[33] to assure the Board of Governors and Chancellor's Office remain responsive in this respect.

The system is administered by the Chancellor's Office located in Sacramento, which is responsible for allocating state funding and provides leadership and technical assistance to the colleges. The Chancellor brings policy recommendations to the Board of Governors, and possesses the authority to implement the policies of the Board through his leadership of the Chancellor's Office. The Chancellor plays a key role in the consultation process.

The CCC is a founding and charter member of CENIC, the Corporation for Education Network Initiatives in California, the nonprofit organization which provides extremely high-performance Internet-based networking to California's K-12 research and education community.

Student government

California Education Code § 76060 allows the governing board of a community college district to authorize the students of a college to organize a student body association.[34] The student body association may conduct any activities, including fundraising activities, that is approved by the appropriate college officials.[34] The governing board of the community college district may also authorize the students of a college to organize more than one student body association when the governing board finds that day students and evening students each need an association or geographic circumstances make the organization of only one student body association impractical or inconvenient.[34]

Students have a right to participate. The BOG has established minimum standards governing procedures established by governing boards of community college districts to ensure faculty, staff, and students the right to participate effectively in district and college governance, and the opportunity to express their opinions at the campus level and to ensure that these opinions are given every reasonable consideration.[35][36] The BOG standards state that the governing board of a community college district shall adopt policies and procedures that provide students the opportunity to participate effectively in district and college governance, including:[37]

The governing body of the association may order that an election be held for the purpose of establishing a student representation fee of $1 per semester, and a student may, for religious, political, financial, or moral reasons, refuse to pay the student representation fee in writing at the time the student pays other fees.[38] Regulations in the California Code of Regulations (CCR) require district governing boards to include information pertaining to the representation fee in the materials given to each student at registration, including its purpose, amount, and their right to refuse to pay the fee for religious, political, moral or financial reasons.[39]

The students of this largest system of education in the world are represented through a statewide students' union known as the Student Senate for California Community Colleges (SSCCC). The SSCCC has a General Assembly composed of 116 Delegates selected by the associated students organization at each school. Meetings of the General Assembly are held once in the Spring in each academic year to vote on "resolutions" of what the organization shall advocate for in the upcoming school year and to elect the new president and 5 vice-presidents. The SSCCC has 10 regional subdivisions and each subdivision or "Region" annually elects two Directors to serve on the SSCCC Board of Directors composed of 10 Regional Affairs Directors, 10 Legislative Affairs Directors, and six Board Officers. Meetings of the Board of Directors are held about 12 times during each academic year. The Board of Directors may nominate students for appointment to seats on the Board of Governors and it may appoint two representatives to the Chancellor's Consultation Council.

Campuses

Students

The 1.8 million students of the California Community Colleges serve as the basis for the economic revitalization of California's workforce. Through its vocational endeavors, the CCC system has played a pivotal role in preparing nurses, firefighters, police, welders, auto mechanics, airplane mechanics, and construction workers to help mold the society of California. Career technical education (CTE), also known as vocational training, connects students to these career opportunities by providing industry-based skills.

In 2017, California sought to eliminate the lingering stigma around CTE. The state's goal was to train and place one million workers in middle-skill jobs, meaning jobs requiring some education beyond a high school diploma which may include a college credential, but not a four-year degree. A core barrier to the growth of CTE careers is the outdated view about the jobs being dirty and low paying. Annual events such as Manufacturing Day address these misperceptions of careers in the field by providing manufacturers an opportunity to bring middle and high school students into their facilities to display the skills required in certain fields. According to the World Economic Forum, more than half of the current workforce will need to be reskilled by 2022.[citation needed]

Enrollment

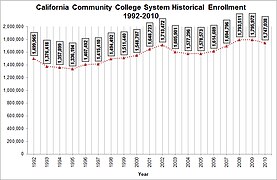

- Enrollment statistics

-

Historical enrollment

-

Gender composition

| Students[40] | California[41] | United States[41] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | 10.4% | 15.3% | 5.8% |

| Black | 5.6% | 5.1% | 11.7% |

| Filipino | 2.5% | N/A | N/ |

| Hispanic (of any race) |

49.1% | 40.4% | 19.2% |

| Non-Hispanic White | 23.0% | 33.7% | 57.7% |

| Native American | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.5% |

| Pacific Islander | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.2% |

| Multi-ethnic | 4.3% | 4.9% | 4.9% |

| Unknown | 4.5% | N/A | N/A |

Faculty and staff

The California Community Colleges had a total employee headcount of 89,497 in fall 2006. While tenured and tenure tracked faculty were relatively well-compensated, they comprise a very small fraction of overall faculty compared to California's other two tertiary education systems. While 86% of CSU faculty members were tenured or tenure-tracked, only 30% of CCCS faculty were tenured or tenure-tracked. Temporary faculty, those who are not tenure tracked, earned an average of $62.86 per hour for those teaching for-credit courses, $47.46 for non-credit instruction, $54.93 for instructional support and $63.86 for "overload" instruction.[43]

Staff and faculty compensation varied greatly by district. The overall average salary for tenured and tenure tracked faculty was $78,498 as of Fall 2006, with 48.7% earning more than $80,001. Salaries ranged from $64,883 in Siskiyous to $90,704 in Santa Barbara. The average for educational administrators was $116,855, while classified administrators earned an average of $87,886, classified professional earned $62,161 and classified support staff earned an average of $43,773.[44]

| Data[44] | Headcount | Percentage of total | Less than $25,000 | $25,000 to $40,000 | $40,000 to $50,000 | $50,000 to $60,000 | $60,000 to $70,000 | $70,000 to $80,000 | More than $80,000 | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational administrators | 1,965 | 2.2% | 1.93% | 0.51% | 0.92% | 0.97% | 1.42% | 2.85% | 90.08% | $116,855 |

| Tenured and tenure tracked faculty | 18,196 | 20.3% | 0.21% | 0.92% | 2.21% | 7.85% | 16.24% | 23.10% | 48.70% | $78,498 |

| Classified administrators | 1,470 | 2.0% | 1.6% | 1.22% | 4.29% | 8.71% | 11.29% | 15.24% | 57.69% | $87,816 |

| Classified professionals | 1,817 | 2.0% | 7.82% | 7.93% | 10.24% | 18.66% | 17.56% | 14.14% | 21.79% | $62,161 |

| Classified support staff | 24,425 | 27.3% | 10.51% | 25.85% | 30.62% | 16.68% | 7.42% | 2.80% | 1.85% | $43,773 |

| Academic temporary instructors | 41,624 | 46.5% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Accreditation

In 2006, Compton College in Compton, California lost its accreditation. Arrangements were made to have the college's governance transferred to El Camino College, a neighboring college.[45] Its new name, as a division of El Camino College, was "El Camino College Compton Center." Under El Camino College the "Center" was fully accredited. Compton College was re-established as a separate college in 2017.[26][27]

In July 2013, City College of San Francisco was notified by its accreditor, the (ACCJC), that its accreditation would be revoked in 2014 if the college failed an appeals process. Brice Harris, the systemwide chancellor of the California Community Colleges system, then appointed a "special trustee with extraordinary powers," an individual granted unilateral powers, to attempt to bring the college back into compliance with the ACCJC's accreditation standards.[46] In January 2017, CCSF was reaffirmed of its accreditation for the full seven-year term by the ACCJC.[47]

See also

References

- ^ a b California Education Code Section 70900 (added to the Education Code by Chapter 973 of the California Statutes of 1988; Assembly Bill No. 1725, section 8, page 17).

- ^ "California community colleges eye a different future amid pandemic disruption". EdSource. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ Board of Governors Archived 2007-04-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Boggs, George R. (2021). "Chapter 1: Beginnings". In Boggs, George R.; Galizio, Lawrence A. (eds.). A College for All Californians: A History of the California Community Colleges. New York: Teachers College Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 9780807779873. (At p. 2.)

- ^ a b Boggs, George R. (2021). "Chapter 1: Beginnings". In Boggs, George R.; Galizio, Lawrence A. (eds.). A College for All Californians: A History of the California Community Colleges. New York: Teachers College Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 9780807779873. (At p. 3.)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Boggs, George R. (2021). "Chapter 1: Beginnings". In Boggs, George R.; Galizio, Lawrence A. (eds.). A College for All Californians: A History of the California Community Colleges. New York: Teachers College Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 9780807779873. (At p. 4.)

- ^ Boggs, George R. (2021). "Chapter 1: Beginnings". In Boggs, George R.; Galizio, Lawrence A. (eds.). A College for All Californians: A History of the California Community Colleges. New York: Teachers College Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 9780807779873. (At p. 5.)

- ^ a b Douglass, John Aubrey (2000). The California Idea and American Higher Education: 1850 to the 1960 Master Plan. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 126. ISBN 9780804731898.

- ^ a b c d e Boggs, George R. (2021). "Chapter 1: Beginnings". In Boggs, George R.; Galizio, Lawrence A. (eds.). A College for All Californians: A History of the California Community Colleges. New York: Teachers College Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 9780807779873. (At p. 6.)

- ^ Galizio, Lawrence A. (2021). "Chapter 2: California Community College Governance". In Boggs, George R.; Galizio, Lawrence A. (eds.). A College for All Californians: A History of the California Community Colleges. New York: Teachers College Press. pp. 16–29. ISBN 9780807779873. (At p. 18.)

- ^ a b c d e Galizio, Lawrence A. (2021). "Chapter 2: California Community College Governance". In Boggs, George R.; Galizio, Lawrence A. (eds.). A College for All Californians: A History of the California Community Colleges. New York: Teachers College Press. pp. 16–29. ISBN 9780807779873. (At p. 19.)

- ^ a b Boggs, George R. (2021). "Chapter 1: Beginnings". In Boggs, George R.; Galizio, Lawrence A. (eds.). A College for All Californians: A History of the California Community Colleges. New York: Teachers College Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 9780807779873. (At p. 7.)

- ^ a b c d e Boggs, George R. (2021). "Chapter 1: Beginnings". In Boggs, George R.; Galizio, Lawrence A. (eds.). A College for All Californians: A History of the California Community Colleges. New York: Teachers College Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 9780807779873. (At p. 8.)

- ^ a b c d Boggs, George R. (2021). "Chapter 1: Beginnings". In Boggs, George R.; Galizio, Lawrence A. (eds.). A College for All Californians: A History of the California Community Colleges. New York: Teachers College Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 9780807779873. (At p. 9.)

- ^ a b c Boggs, George R. (2021). "Chapter 1: Beginnings". In Boggs, George R.; Galizio, Lawrence A. (eds.). A College for All Californians: A History of the California Community Colleges. New York: Teachers College Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 9780807779873. (At p. 10.)

- ^ Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 183. ISBN 9780520223677.

- ^ a b c d Galizio, Lawrence A. (2021). "Chapter 2: California Community College Governance". In Boggs, George R.; Galizio, Lawrence A. (eds.). A College for All Californians: A History of the California Community Colleges. New York: Teachers College Press. pp. 16–29. ISBN 9780807779873. (At p. 22.)

- ^ a b Boggs, George R. (2021). "Chapter 1: Beginnings". In Boggs, George R.; Galizio, Lawrence A. (eds.). A College for All Californians: A History of the California Community Colleges. New York: Teachers College Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 9780807779873. (At p. 14.)

- ^ Gerth, Donald R. (2010). The People's University: A History of the California State University. Berkeley: Berkeley Public Policy Press. pp. 461–462. ISBN 9780877724353.

- ^ LHC 2012, p. 6.

- ^ LHC 2012, p. 7.

- ^ California Education Code Section 70900.5.

- ^ Larry Gordon, "California universities consider adopting the T-word: tuition", Los Angeles Times, June 14, 2010.

- ^ California Community Colleges: Year Built

- ^ Anthony Galaviz, "Junior colleges: Clovis Community launches swim and dive team", Fresno Bee, February 7, 2017.

- ^ a b "Compton College Gets Its Accreditation Restored", NBC Los Angeles, June 9, 2017.

- ^ a b "Compton Community College District Substantive Change Application Approved", Los Angeles Sentinel, August 30, 2018.

- ^ Nanette Asimov, "Heather Hiles, chief of California's new online community college, resigns", San Francisco Chronicle, January 14, 2020.

- ^ Dustin Gardiner, "California's online-only community college is flunking out with legislators", San Francisco Chronicle, June 10, 2020.

- ^ "Board of Governors Recognizes Madera Community College as the 116th Community College in California | California Community Colleges Chancellor's Office". www.cccco.edu. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Murtaugh, Isaiah (October 23, 2023). "Oxnard College, Ventura College set for bachelor's degree programs". Ventura County Star. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- ^ "California Education Code Section 71000". Archived from the original on June 20, 2010. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ^ Chancellor's Consultation Council Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c California Education Code § 76060 Archived 2012-11-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chapter 973 of the California Statutes of 1988

- ^ California Education Code § 70901(b)(1)(E)

- ^ 5 CCR § 51023.7

- ^ California Education Code § 76060.5 Archived 2012-11-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 5 CCR § 54805

- ^ "Enrollment Status Summary Report". California Community Colleges Chancellor's Office. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ a b "Population Distribution by Race/Ethnicity". Kaiser Family Foundation. October 28, 2022. Archived from the original on May 22, 2024.

- ^ | Chancellor's Office | Data Mart Archived 2012-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "California Community Colleges Chancellor's Office. (April 26, 2007). Report on Staffing for Fall 2006: Statewide Summary" (PDF). Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ^ a b "California Community Colleges Chancelor's Office. (Fall, 2006). Employee Category Salary Distribution by District" (PDF). Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ^ CSU | Public Affairs | Daily Clips. Calstate.edu. Retrieved on 2013-08-09.

- ^ City College of S.F. trustees lose power. SFGate (2013-07-09). Retrieved on 2013-08-09.

- ^ Xia, Rosanna (January 20, 2017). "City College of San Francisco wins back accreditation after years of uncertainty". LA Times. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

Further reading

- Milton Marks Commission on California State Government Organization and Economy (February 2012). Serving Students, Serving California: Updating the California Community Colleges to Meet Evolving Demands (PDF). Sacramento: State of California. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

External links

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !