Eduard Roschmann

Eduard Roschmann | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Eduard Roschmann 25 November 1908 |

| Died | 8 August 1977 (aged 68) |

| Nationality | |

| Other names | Federico/Frederico Wegener/Wagner |

| Known for |

|

| Political party | NSDAP |

| Criminal charges | |

| Military career | |

| Nickname(s) | The Butcher of Riga |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1939–45 |

| Rank | SS-Hauptsturmführer |

| Service number | SS #152,681 |

Eduard Roschmann (25 November 1908 – 8 August 1977) was an Austrian Nazi SS-Obersturmführer[1] and commandant of the Riga Ghetto during 1943. He was responsible for numerous murders and other atrocities. As a result of a fictionalized portrayal in the novel The Odessa File by Frederick Forsyth and its subsequent film adaptation, Roschmann came to be known as the "Butcher of Riga".[2]

Early life and career

Roschmann was born on 25 November 1908, in Graz-Eggenberg, in Austria.[3] He was the son of a brewery manager.[4] He was reputed to have come from the Styria region of Austria, from a good family.[5] From 1927 to 1934, Roschmann was a member of the Fatherland's Front, which in turn was part of the Austrian home guard ("Heimatschutz"). From 1927 to 1934, Roschmann was associated with an organization called the "Steyr Homeland Protection Force." Roschmann spent six semesters at a university. Contrary to a report that he was once a lawyer in Graz, Austria,[6] he had studied to be a lawyer but failed.[7] By 1931, he was a brewery employee, joining the civil service in 1935. In May 1938, he joined the Nazi Party NSDAP Number 6,276,402, and the SS the following year. In January 1941, he was assigned to the Security Police.[4]

War crimes in Latvia

Within the SS Roschmann was assigned to the Security Service (Sicherheitsdienst), often referred to by its German initials SD. Following the German occupation of Latvia in the Second World War, the SD established a presence in Latvia with the objective of killing all the Jews in the country.[citation needed] To this end, the SD established the Riga ghetto.

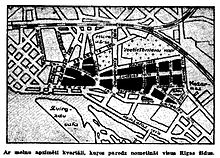

Structure of the Riga ghetto

The Riga ghetto did not exist prior to the occupation of Latvia by the German armed forces. Jews in general lived throughout Riga before then. The ghetto itself was a creation of the SD. Surrounded by barbed wire fences, with armed guards, it was in effect a large and overcrowded prison. Furthermore, while it is common to see the Riga ghetto referred to as a single location, in fact it was a unified prison for only a very short time in autumn of 1941. After that it was split into three ghettos.

The first ghetto was the Latvian ghetto, sometimes called the "Big Ghetto", which was in existence for only 35 days, from late October to 30 November 1941. Men, women and children were forced into the ghetto, where at least for a short time they lived as families. On 30 November and on 8 December 1941, 24,000 Jews were force-marched out of the ghetto and shot at the nearby forest of Rumbula. Except for Babi Yar, this was the biggest two-day massacre in the genocides until the construction of the death camps in 1942.[8] A few thousand Latvian Jews, mostly men, who were not murdered at Rumbula, were confined to a much smaller area of the former Latvia ghetto. This became known as the men's ghetto; about 500 Latvian Jewish women, who were also not selected for murder, were similarly confined to an adjacent but separated smaller ghetto, known as the women's ghetto.

A few days after the 8 December massacre, train-loads of Jews from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia began to arrive in Riga, where, with some important exceptions, they were housed in a portion of the former Latvian ghetto, which then became known as the German ghetto.[9]

Participation in Dünamünde Action

In March 1942, the German authorities in charge of the Riga ghetto and the nearby Jungfernhof concentration camp murdered about 3,740 German, Austrian and Czech Jews who had been deported to Latvia. The victims were mostly the elderly, the sick and infirm and children. These people were tricked into believing they would be transported to a new and better camp facility at an area near Riga called Dünamünde. In fact no such facility existed, and the intent was to transport the victims to mass graves in the woods north of Riga and shoot them.[10][11]

According to a survivor, Edith Wolff, Roschmann was one of a group of SS men who selected the persons for "transport" to Dünamünde.[note 1] Wolff stated that only the "prominent people" made selections, and she was not sure whether others in the selection group like Kurt Migge, Richard Nickel, or Rudolf Joachim Seck had picked anyone.[12]

Appointment as ghetto commandant

Starting in January 1943, Roschmann became commandant of the Riga ghetto.[1][6] His immediate predecessor was Kurt Krause. Survivors described Krause as "sadistic",[6]"bloody",[13] "monster",[14] and "psychopath".[13] Roschmann's methods differed from those of Krause. Unlike Krause, Roschmann did not execute offenders on the spot, but, in most cases, sent them to Riga's Central Prison. Whether this was a matter of having qualms about murder is not certain.[6] However, being sent to the prison was likely to be, at best, only a brief reprieve, as conditions there were brutal.[15]

At that time, Roschmann held the relatively low rank of Unterscharführer.[16] Differing ranks are supplied for Roschmann. According to Ezergailis and Kaufmann, Roschmann held the rank of SS-Unterscharführer.[1] According to Schneider, Roschmann was an SS-Obersturmführer, a higher rank. Schneider mentions no promotion for Roschmann.

Murders and other crimes

Historians Angrick and Klein state that in addition to the mass killings, the Holocaust in Latvia also consisted of a great number of individual murders.[17]

... the reading provided by witness accounts ... makes it clear that the genocide in occupied Riga consisted of an enormous number of individual murders in addition to the large-scale operations. The image of the Holocaust in Latvia conveyed in these reports is not that of a gigantic impersonal killing machine, even if the plans for shooting the Jews of Riga in winter 1941 conjure up a process of mass murder based on division of labour. The overall pattern in these accounts is dominated by individual murders committed out of a desire to kill, punish or deter.[17]

Angrick and Klein name Roschmann among others as responsible for these individual murders.[17] Historian Schneider, a survivor of the German ghetto, has stated that it is certain that Roschmann was a murderer, otherwise he never would have risen as high as he did in the SS.[6] One documented murder committed by Roschmann, with his subordinates assisted by Scharführer[18] Max Gymnich and Kurt Migge, was that of Arthur Kaufmann, the 17-year-old son of Max Kaufmann, who later came to write one of the first histories of the Holocaust in Latvia. Roschmann personally issued the order for this particular murder.[6][19] Kaufmann himself described the murder, which occurred when both of them were housed outside the ghetto at the Sloka work camp, where among other things they were tasked with peat cutting:

On 20 May 1943 the Commandant of our ghetto, Roschmann, came to Sloka together with his adjutant Gymnich and the SD man Migge. They inspected the entire work camp, and on this occasion they discovered that my son and the Mordchelewitz brothers were hoarding fat. Because all the members of the work crew were working, nobody was present at this inspection. A short time later the three of them were taken away, and the murderers immediately placed my son and the Mordechelewitz brothers off to the side next to their vehicle. They were ordered to take off their shoes, and from this moment on the "guilty ones" knew they were going to be shot. The Mordechelewitz brothers tried to escape. The guards ran after them and shot them. By contrast, my son behaved like a hero. He was much too proud to beg for mercy. He was killed immediately with a shot to the back of the neck. When everyone came back from work in the evening, the mood was very low. My son had been the work crew's favourite, and his death was deeply mourned.[20]

Food for ghetto occupants was strictly rationed and generally inadequate. It was common for Jews assigned to work details to obtain and attempt to smuggle extra food into the ghetto. For this and other reasons, all returning work details were subject to search, although this was actually carried out only on a sporadic basis. When searches did occur, those smuggling food were forced to abandon it before it could be found on their person, which was a serious offence.[5] Roschmann and his aide, Max Gymnich, accompanied by a trained attack dog, involved themselves in the details of the searches for contraband food, which included inspections of kitchens in the ghetto, again forcing people to discard food they had smuggled in, even when they were about to eat it.[5] Survivor Nina Ungar related a similar incident at the Olaine peat bog work camp, where Roschmann found three eggs on one of the Latvian Jews and had him shot immediately.[14] Kaufmann describes an incident, possibly the same one referred to by Ungar, where Roschmann, during a visit to the Olaine work camp with Gymnich in 1943, found a singer named Karp with five eggs and had him shot immediately.[21]

Roschmann, together with Krause, who, although no longer ghetto commandant, was close at hand as the commandant of the Salaspils concentration camp, investigated a resistance plot among the Jews to store weapons at an old powder magazine in Riga known as the Pulverturm. As a result, several hundred inmates were executed, whom Kaufmann described as "our best young people."[5]

While ghetto commandant, Roschmann became involved with the work detail known as the Army Motor Park (Heereskraftpark).[22] This was considered a favourable work assignment for Jews, as it involved skilled labour (vehicle mechanics) necessary for the German army, thus providing some protection from liquidation, and it also gave a number of opportunities to "organise" (that is, to buy, barter for or steal) contraband food and other items. The Jews on the work detail benefited from the fact that the German in charge, Private First Class (Obergefreiter) Walter Eggers, was corrupt and wanted to use the Jews under his command to become rich. Consequently, better treatment could be had, at least for a time, by paying Eggers bribes. Roschmann heard rumours about the "good life",[23] and attempted to prevent it by putting some of the workers into one of the prisons or transferring them to Kaiserwald concentration camp.[22]

Roschmann himself was not above accepting bribes, or at least pretending to accept bribes. In one instance, a shoemaker whose two children had been incarcerated in the Riga prisons as a result of Roschmann's investigation, attempted to secure their release by paying Roschmann a large number of gold coins. Roschmann took the coins, but did not release the children.[24]

Actions outside of the ghetto

Roschmann was later transferred to the Lenta work camp, a forced-labour facility in the Riga area where Jews were housed at the workplace.[1] Originally this facility had been located on Washington (Ludendorff) Square in Riga and had been known as the "Gestapo" work detail.[25] Lenta was considered a favoured work assignment. The original German commandant, Fritz Scherwitz, had determined to make a lot of money involving the work of highly skilled Jews in the tailoring trade. Scherwitz made efforts to protect Jews in the Lenta work detail. This changed when Roschmann became the Lenta commandant. According to Kaufmann:

Under the rule of this Commander Roschmann the camp's inmates experienced especially difficult times. This was why various inmates * * * escaped to Dobele in Kurzeme. * * * As a collective punishment, the lovely grey suits were striped with white oil paint, the men had a stripe shaved down the middle of their heads, and the women all had their hair cut off. Others were arrested, sent to prison and murdered there.[22]

Roschmann participated in the efforts of Sonderkommando 1005 to conceal the evidence of the Nazi crimes in Latvia by exhuming and burning the bodies of the victims of the numerous mass shootings in the Riga area.[4] In the fall of 1943, Roschmann was made the chief of Kommando Stützpunkt, a work detail of prisoners which was given the task of digging up and burning the bodies of the tens of thousands of people whom the Nazis had shot and buried in the forests of Latvia. About every two weeks the men on the work detail were shot and replaced with a new set of inmates.[26][27] Men for this commando were selected both from Kaiserwald concentration camp and from the few remaining people in the Riga ghetto.

Historian Ezergailis states that one Hasselbach, an SS officer, was the commander of the Stützpunkt commando, and does not mention Roschmann.[28] As his source, Ezergailis cites a witness, Franz Leopold Schlesinger, who testified in the trial in West Germany of Viktors Arajs in the late 1970s, almost 35 years later. Schlesinger in turn appears to have only "thought" Hasselbach was the commander.[28]

Roschmann is sometimes described as the commandant of the Kaiserwald concentration camp, which was located on the north side of Riga. Kaufmann however gives the Kaiserwald commandant as an SS man named Sauer who held the rank of Obersturmbannführer.[29]

Jack Ratz, a Latvian Jewish survivor, came face to face with Roschmann in Lenta at the age of 17. According to Jack:

Since I worked in the kitchen I became a "chemist". I took horse fat, beef fat, and bacon, melted them together with onions, and created a smear on bread. One day Roschmann came into the barracks with his dog. The dog smelled something unusual and pulled his master over to my locker where I had hidden my food. The SS officer forced me to empty all the food from my locker and called the doctor in from the next building to taste the food to find out why it had such unusual smell.

The doctor, who was my friend because I had often supplied him extra food, gave me a wink as he tasted the food and reported that the odor came from onions. But the Nazi wanted to know how it came about that I had so much food and fats in my locker, since the food allowance was only enough for one or two days, at most. I told him that the food was not only my own, but I was also holding rations for my father and his friend.

He then ordered the chief of police, a German Jew, to bring my father to the kitchen. My father was forced to run down a few flights of stairs so that the Nazi should not have a long wait. When asked what he did with his ration of food, my father unhesitatingly replied, "Me? All my food goes to my son." The Nazi walked out, and that time I emerged the winner with my life. Once again I was rescued from the firing squad, this time by my father's quick thinking.

Character

According to Gertrude Schneider, a historian and a survivor of the Riga ghetto, Roschmann was clearly a murderer, but was not uniformly cruel. She records an instance where Krause, Roschmann's predecessor as commandant, had executed Johann Weiss, a lawyer from Vienna, and a First World War veteran, for having hidden money in his glove. A year later, when Roschmann was commandant, his widow and daughter requested of him that he allow them the Jewish custom of visiting the grave. Roschmann allowed the request.[30]

Schneider, in describing this incident, characterised Roschmann as "that most peculiar SS man."[30] According to Schneider, Roschmann would order food abandoned during searches for contraband to be sent to the ghetto hospital.[31] Schneider particularly objected to Roschmann's modern image as the so-called "butcher of Riga". Up to the time of the publication of Forsyth's book in 1972, Herberts Cukurs, a famous Latvian pilot, had been the person known as "the Butcher of Riga" as a result of his actions during the occupation of Latvia from 1941 to 1944.:[32][33][34][35][36]

[I]t would be a mockery to single out Roschmann as "butcher" and ignore all the others. Roschmann ... probably preened himself in front of his SS cronies when citing The Odessa File as proof of his ruthless efficiency three decades earlier. Actually, however, he was hardly a "mass murderer." The atrocities mentioned in The Odessa File occurred long before he came on the scene. What he actually did in the ghetto was far less exciting: he would spend hours on end just standing in front of the Kommandantur, not knowing what to do with himself. From time to time he would sneak a look inside the hospital, but mostly he would walk around aimlessly, growing fatter by the day, more or less ignored by everyone.[37]

However, other accounts assign a more malignant role to Roschmann. Historian Bernard Press, a Latvian Jew who was able to hide outside of Riga and avoid confinement in the ghetto, describes Krause, Gymnich and Roschmann as having engaged in random shootings of human beings.[38] Press describes an incident where a woman was condemned to death for "illegal correspondence" with a friend in Germany. Roschmann had her confined in the Central Prison, where she was not in fact executed but released based on the recommendation of Krause, who had previously wanted the woman to become his mistress.[39]

Also, Max Michelson described Roschman, Rudolf Lange and Kurt Krause as all being "notorious sadists."[40] Michelson, a Riga ghetto survivor, described Roschmann:

When Krause was replaced by Roschmann in early 1943, we were happy finally to be rid of this madman. Roschmann, a lawyer, was indeed more deliberate, less likely to react by killing his victims on the spur of the moment. Roschmann, however, was a careful and meticulous investigator who would incarcerate and interrogate suspects and implicate and arrest many more people than Krause had. As a result, our situation did not improve, and the number of people killed under Roschmann was even larger than under Krause.[40]

Max Kaufmann, a survivor of Latvian ghetto, compared Roschmann to Krause, coming to a similar conclusion as Max Michelson:

Krause, a psychopath and a sadist, acted suddenly and spontaneously, handing down his verdicts without a detailed explanation of the situation and executing them immediately. Roschmann, the jurist, deliberated for a long time, investigated thoroughly, and thus pulled down more and more people to their destruction.[13]

Flight from Latvia

In October 1944, out of fear of the approaching Soviet armies, the SS personnel of the concentration camp system in Latvia fled the country by sea from Riga or Liepāja to Danzig, taking with them several thousand concentration camp inmates, many of whom did not survive the voyage.[41]

Escape to Argentina

In 1945, Roschmann was arrested in Graz, but later released.[3] Roschmann concealed himself as an ordinary prisoner of war, and in so doing obtained a release from custody in 1947. After visiting his wife in Graz, he was recognised with the assistance of former concentration camp inmates and arrested by the British military police. Roschmann was sent to Dachau concentration camp which had been converted to an imprisonment camp for accused war criminals. Roschmann succeeded in escaping from this custody; in the process while running in hiding from a British patrol at the Austrian Border he was shot through the lung and also lost two toes of one foot to frostbite.[42] In 1948 Roschmann was able to flee Germany. He travelled first to Genoa in Italy, and from there to Argentina by ship, on a pass supplied by the International Red Cross. Roschmann was assisted in this effort by Alois Hudal, a strongly pro-Nazi bishop of the Catholic Church.[43] Roschmann arrived in Argentina either on 10 February 1948[3] or 2 October 1948[43] (2/10/1948 or 10/2/1948, depending on date notation used). He founded a wood import-export firm in Buenos Aires.[3] In 1955 in Argentina Roschmann married, although he was not divorced from his first wife. His second wife left him in 1958; the marriage was later declared null and void.[44] In 1968, under the name "Frederico Wagner" (sometimes seen as "Federico Wegener") he became a citizen of Argentina.[3]

Criminal charges

In 1959, a warrant was issued in Germany for Roschmann on a charge of bigamy.[44] In 1960, the criminal court in Graz issued a warrant for the arrest of Roschmann on charges of murder and severe violations of human rights in connection with the killing of at least 3,000 Jews between 1938 and 1945, overseeing forced labourers at Auschwitz, and the murder of at least 800 children under the age of 10.[3] However, the post-war Austrian legal system was ineffective in securing the return for trial of Austrians who had fled Europe, and no action was ever taken against Roschmann based on this charge. In 1963, the district court in Hamburg, West Germany, issued a warrant for the arrest of Roschmann. This would eventually prove a more serious threat to Roschmann.[3]

Extradition negotiations

In October 1976, the embassy of West Germany in Argentina initiated a request for the extradition of Roschmann to Germany to face charges of multiple murders of Jews during the Second World War. This was based on the request of the West German prosecutor's office in Hamburg.[3] The request was repeated in May 1977.[45] On 5 July 1977, the office of the President of Argentina issued a communiqué, which was published in the Argentine press, that the government of Argentina would consider the request even though there was no extradition treaty with West Germany.[45] The communiqué was reported to be a surprise to both the Argentine Foreign Ministry and the West German embassy.[45] The Argentine Foreign Embassy had not received a request that Roschmann be arrested. Roschmann was in fact still not under arrest at the time the communiqué was issued.[45]

At that time, a number of Germans had been arrested by the Argentine government, then under military control, and were facing charges before military tribunals. The Argentine government had also failed to account for the death of a West German citizen in unusual circumstances, apparently related to the conduct of the so-called Dirty War then being conducted by the Argentine government against alleged terrorists within the country. This was regarded by the West German government as a breach of international treaty obligations.[45] In addition, the prominent Argentine journalist, Jacobo Timmerman, a Jew, had been arrested at that time and held incommunicado under circumstances which raised concern that he had been "subjected to ill-treatment" while in custody.[45]

Roschmann then fled to Paraguay.[3]

The U.S. Embassy in Argentina sent a cable to the State Department which reported the situation and contained the following comment:

The public and undiplomatic handling of the Argentine announcement concerning Roschmann raised speculation that it was a political move designed to placate the West Germans of human rights complaints and throw off charges of anti-Semitic attitudes within the government. ... [T]he timing of the announcement on the extradition case appears to be an effort to appease an irate West German government. It has also been noted that the publicity surrounding the announcement will give Roschmann adequate time to prepare for avoiding arrest.[45]

Death

Roschmann died in Asunción, Paraguay, on 8 August 1977.[3] The body initially went unclaimed, and questions were raised as to whether the dead man was, in fact, Roschmann.[46] The body bore papers in the name of "Federico Wegener", a known Roschmann alias, and was missing two toes on one foot and three on the other, consistent with Roschmann's known post-war injuries.[46] Emilio Wolf, a delicatessen owner in Asunción who had been a prisoner under Roschmann, positively identified the body as Roschmann's. Simon Wiesenthal, however, was sceptical of the identification, claiming that a man matching Roschmann's description had been spotted in Bolivia only one month earlier. "I wonder who died for him?" he said.[46]

On the other hand, a report made five days after his death stated that the international police agency Interpol had confirmed the fingerprints on the body as matching prints of Roschmann on file at Argentina's police agency in Buenos Aires, and Wiesenthal said at that time that although he at first had doubted Paraguayan reports, he was "75 percent sure" that the body was that of Roschmann. [47]

Fictional portrayal

A fictionalised version of Roschmann was given in Frederick Forsyth's novel The Odessa File. A film version of the novel was released in 1974, where Roschmann was played by Austrian actor Maximilian Schell.[48] In the book and the film, Roschmann is portrayed as a ruthlessly efficient killer. Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal was portrayed in the film by actor Shmuel Rodensky. Wiesenthal himself also functioned as a "documentary advisor".[48] Historian Schneider sharply disputes this fictionalised image of Roschmann. She describes this fiction novel as "lurid" and containing "many inaccuracies".[2] Among the inaccuracies of Forsyth's fictional version of Roschmann are:

- Roschmann never murdered a Wehrmacht captain at the Latvian port of Liepāja to force his way onto an evacuation ship.[49]

- No mention is made of Rudolf Lange, whom Schneider describes as the real Butcher of Riga.

- Krause is portrayed as Roschmann's deputy, rather than as his predecessor.[6]

- Alois Hudal is incorrectly identified as the "German apostolic nuncio" and a cardinal.[50]

- Roschmann is described as having been sheltered in a "big" Franciscan house in Genoa which apparently never existed.[50]

- ODESSA is portrayed as having purchased 7,000 Argentinian passports for people like Roschmann. No explanation is given for why, if this were so, Roschmann would need a travel document from the International Red Cross.[50]

- The head of ODESSA is identified as former SS General Richard Glücks, who in fact committed suicide in 1945.

- The head of ODESSA in Germany is a former SS Officer called the "Werwolf", who is implied to be SS General Hans-Adolf Prützmann who in fact committed suicide in 1945.

Researcher Matteo San Filippo, who studied the issue of the discrepancies between the fictional and the real Roschmann, gives the following analysis: "We cannot blame Forsyth for being inaccurate. He was writing a thriller, not an historical essay. The incidents were based on fact and the overall impression was not inaccurate (for example, some religious houses did shelter the wanted, just not in Genoa. Roschmann did murder many people, but not a Wehrmacht captain. ODESSA did supply faked travel documents of different kinds. And so on)."[50]

The role of Wiesenthal in the genesis of the novel is more interesting.[according to whom?] Later, the Nazi hunter confessed that he wanted to influence the writer. In fact, Wiesenthal was using the thriller to force Roschmann out into the open, which is what actually happened. Wiesenthal himself, in his 1990 book Justice Not Vengeance, admitted that he had suggested, in response to Forsyth's inquiry, that Forsyth's book, and the later film, include fictional statements about Roschmann, and that he, Wiesenthal, had done so for the purpose of casting the light on Roschmann and forcing his arrest.[51] Ironically Roschmann was eventually identified and denounced by a man who had just watched The Odessa File at the cinema.[52]

See also

- Riga Ghetto

- The Holocaust in Latvia

- The Odessa File, fictionalised 1972 novel by Frederick Forsyth that cast Roschmann back into public attention

Notes

- ^ Others in the selection group included Rudolf Lange, Kurt Krause, Max Gymnich, Kurt R. Migge, Richard Nickel and Rudolf Seck.

References

- ^ a b c d Ezergailis (1996), pp. 152, 382.

- ^ a b Schneider (1995), p. 78.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rathkolb (2004), p. 232–7, 264.

- ^ a b c Angrick & Klein (2012), p. 479.

- ^ a b c d Kaufmann (1947).

- ^ a b c d e f g Schneider (1979), p. 75.

- ^ The Odessa File

- ^ Ezergailis (1996), p. 239.

- ^ Schneider (1979), p. 162.

- ^ Kaufmann (1947), p. 47.

- ^ Schneider (1979), pp. 34–7.

- ^ Angrick & Klein (2012), p. 330.

- ^ a b c Kaufmann (1947), p. 72.

- ^ a b Schneider (1991), p. 112.

- ^ Kaufmann (1947), pp. 85–7.

- ^ Kaufmann (1947), pp. 72–98, 134–7.

- ^ a b c Angrick & Klein (2012), pp. 389–90.

- ^ Ezergailis (1996), pp. 380–83.

- ^ Press (2000), p. 151.

- ^ Kaufmann (1947), p. 97.

- ^ Kaufmann (1947), p. 158.

- ^ a b c Kaufmann (1947), pp. 135–7.

- ^ Kaufmann (1947), p. 136.

- ^ Kaufmann (1947), p. 145.

- ^ Kaufmann (1947), pp. 133–5.

- ^ Schneider (1979), p. 76.

- ^ Schneider (1991), p. 62.

- ^ a b Ezergailis (1996), pp. 289, 361.

- ^ Kaufmann (1947), p. 113.

- ^ a b Schneider (1979), p. 45.

- ^ Schneider (1979), p. 79.

- ^ Press (2000), p. 127.

- ^ Künzle & Shimron (2004), pp. 320–351.

- ^ Lumans (2006), p. 240.

- ^ Eksteins (2000), p. 150.

- ^ Michelson (2004), pp. 103.

- ^ Schneider (1979), pp. 75–6.

- ^ Press (2000), p. 119.

- ^ Press (2000), pp. 137–8.

- ^ a b Michelson (2004), p. 112.

- ^ Ezergailis (1996), pp. 361–364.

- ^ The Odessa File

- ^ a b Goñi (2002), pp. 243, 250.

- ^ a b "Axis History forum". Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Declassified State Department cable, dated 7 July 1977, ¶12, on pages 5–6 Archived 9 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine (available at U.S. State Dept. Freedom of Information Act website.)

- ^ a b c Associated Press story reprinted in The Free Lance Star, 12 August 1977, page 8 (headline: "Mystery Body may be 'Butcher of Riga'").

- ^ "Interpol Identifies Body as Nazi War Criminal", Los Angeles Times, August 14, 1977, p.I-37

- ^ a b The Odessa File at IMDb

- ^ Wiesenthal (1990), p. 991.

- ^ a b c d San Filippo, Matteo, Ratlines and Unholy Trinities, Siftung für Sozialgeschichte des 20.Jahrhundrets (footnotes omitted from direct quotes).

- ^ Sanders, Robert, "Nazi Hunting: Trails that Never Grow Cold", New York Times, May 13, 1990 review of Wiesenthal, Simon, Justice Not Vengeance, New York: Grove Weidenfeld 1990.

- ^ Brown, Helen (21 May 2011) Frederick Forsyth: 'I had expected women to hate him. But no...’ telegraph.co.uk

Sources

- Angrick, Andrej; Klein, Peter (2012). The 'Final Solution' in Riga: Exploitation and Annihilation, 1941–1944. New York: Berghahn Books. p. 530. ISBN 978-0-857-45601-4. OCLC 848244678.

- Eksteins, Modris (2000). Walking Since Daybreak: A Story of Eastern Europe, World War II, and the Heart of Our Century. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-618-08231-5. OCLC 45165170.

- Ezergailis, Andrew (1996). The Holocaust in Latvia, 1941–1944: the missing center. Washington DC: Historical Institute of Latvia. p. 465. ISBN 978-9-984-90543-3. OCLC 606956247.

- Goñi, Uki (2002). The Real Odessa: Smuggling the Nazis to Perón's Argentina. New York: Granta. p. 410. ISBN 978-1-862-07581-8. OCLC 51231875.

- Kaufmann, Max (1947). Churbn Lettland: The Destruction of the Jews of Latvia. Konstanz: Hartung-Gorre. p. 292. ISBN 978-3-866-28315-2. OCLC 762455912.

- Klee, Ernst (2005). Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich: wer war was vor und nach 1945 (in German). Berlin: Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. p. 732. ISBN 978-3-596-16048-8. OCLC 989166541.

- Künzle, Anton; Shimron, Gad (2004). The execution of the Hangman of Riga: the only execution of a Nazi war criminal by the Mossad. London: Vallentine Mitchell. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-853-03525-1. OCLC 53360827.

- Lumans, Valdis O. (2006). Latvia in World War II. New York: Fordham University Press. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-823-22627-6. OCLC 470476613.

- Michelson, Max (2004). City of Life, City of Death: Memories of Riga. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-87081-642-0. OCLC 912317834.

- Press, Bernard (2000). The Murder of the Jews in Latvia: 1941–1945. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-810-11729-7. OCLC 647592089.

- Rathkolb, Oliver (2004). Revisiting the National Socialist Legacy: Coming to Terms With Forced Labor, Expropriation, Compensation, and Restitution. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-765-80596-6. OCLC 54400242.

- Schneider, Gertrude (1991). The Unfinished Road: Jewish Survivors of Latvia Look Back. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-275-94093-5. OCLC 76038496.

- Schneider, Gertrude (1995). Exile and Destruction: The Fate of Austrian Jews, 1938–1945. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-275-95139-9. OCLC 473180561.

- Schneider, Gertrude (1979). Journey Into Terror: Story of the Riga Ghetto. London: Ardent Media. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-935-76400-0. OCLC 742564301.

- Schneppen, Heinz (2009). Ghettokommandant in Riga Eduard Roschmann: Fakten und Fiktionen (in German). Berlin: Metropol Verlag. p. 343. ISBN 978-3-938-69093-2. OCLC 254721144.

- Wiesenthal, Simon (1990). Justice, Not Vengeance. London: Mandarin Paperbacks. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-749-30265-8. OCLC 22179156.

Further reading

- Katz, Josef (2006). One who Came Back: The Diary of a Jewish Survivor. Takoma Park, MD: Dryad Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-928-75507-4. OCLC 892528656.

- Ratz, Jack (1998). Endless Miracles. Rockville, MD: Shengold. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-884-00202-4. OCLC 808492989.

External links

- Jewish Community in Latvia – Joint project of Latvia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Latvian Jewish Community, and the Democracy Commission of the US Embassy.

- 1908 births

- 1977 deaths

- Austrian exiles

- Austrian expatriates in Argentina

- 20th-century Austrian lawyers

- Austrian Nazis

- Lawyers in the Nazi Party

- Bigamists

- Escapees from British military detention

- Fugitives wanted on crimes against humanity charges

- Fugitives wanted on war crimes charges

- Holocaust perpetrators in Latvia

- Kaiserwald concentration camp personnel

- Military personnel from Graz

- Nazi concentration camp commandants

- Nazis who fled to Argentina

- People convicted of bigamy

- Heimwehr personnel

- Reich Security Main Office personnel

- People of Reichskommissariat Ostland

- Riga Ghetto

- SS-Obersturmführer

- Shooting survivors

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !