Health in Singapore

Singapore is one of the wealthiest countries in the world, with a gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of more than $57,000. Life expectancy at birth is 82.3 and infant mortality is 2.7 per 1000 live births. The population is ageing and by 2030, 20% will be over 65. However it is estimated that about 85% of those over 65 are healthy and reasonably active. Singapore has a universal health care system.

There are a variety of health screening and healthy lifestyle[1] programmes for both adults and children. Only 14% of the population smokes.[2] The Temasek Cares programme supports a wide range of interventions for disadvantaged people.

Singapore in recent years has the lowest infant mortality rate in the world and among the highest life expectancies from birth, according to the World Health Organization.[3]

A new measure of expected human capital calculated for 195 countries from 1990 to 2016 and defined for each birth cohort as the expected years lived from age 20 to 64 years and adjusted for educational attainment, learning or education quality, and functional health status was published by the Lancet in September 2018. Singapore had the thirteenth-highest level of expected human capital with 24 health, education, and learning-adjusted expected years lived between age 20 and 64 years.[4]

Health Indicators

Some common indicators used to indicate health include total fertility rate, infant mortality rate, life expectancy, crude birth and death rate. As of 2017, Singapore has a Total Fertility Rate of 1.16[5] children born per woman, an Infant Mortality rate of 2.2 deaths per 1000 live births,[6] Crude Birth Rate of 8.9 births per 1000 people[7] and a Death Rate of 3 deaths per 1000 inhabitants.[8] The average lifetime expectancy at birth slightly increased from 83 to 83.1 between the period 2016 and 2017.[9] In comparison, the average lifetime expectancy for China grew from 76.3 in 2016 to 76.4 in 2017.[10] Other parameters are outlined below:

| 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy at Birth | 61.3 | 66.0 | 72.2 | 75.3 | 82.0 | 82.3 | 82.55 | 82.8 | 83.0 | 83.1 |

| Total fertility rate (per female) | 5.76 | 3.07 | 1.82 | 1.83 | 1.29 | 1.19 | 1.25 | 1.24 | 1.2 | 1.16 |

| Infant mortality Rate (per 1,000 live births) | 35.6 | 22.0 | 12.0 | 6.2 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Under 5 Mortality Rate/Child mortality (per 1,000 live births) | 47.8 | 27.4 | 14.8 | 7.7 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

In general, all indices showed improvement except for the Total fertility rate, which dropped to 1.16 in 2017, making it the lowest figure since 1.15 in 2010 and the second lowest ever recorded in the city-state. This general slow-down can be explained by the ‘demographic-gift’, term defined by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) according to which increases in income, education and health and the changing role of women in the workforce were strongly connected to levels of low fertility rate.

Age Structure

The median age of the resident population rose from 40.0 years to 40.5 years between June 2016 and June 2017. Residents aged 65 years and over made up 13% of the resident population in Singapore in 2017, compared to 12.4% in 2016.

Dependency Ratio

The Age dependency ratio in Singapore was reported at 37.98% in 2016, according to the World Bank collection of development indicators, and is expected to reach 36.3% by 2030 and 60.6% by 2050.[12] The retired population will therefore make up a growing share of the population in the upcoming years. Factors contributing to this growth include rising life expectancy and falling birth rates.[13]

Medical Issues in Singapore

Malnourishment

Malnourishment is "a condition caused by inadequate, excessive or imbalance intake of nutrients".[14] Common indicators used to measure malnourishment are body mass index and vitamin deficiencies.[14]

Children

From 1977 to 2000, children malnutrition for those aged five and younger had moments of improvement and backtrack.[15] The prevalence of children being underweight, having stunted growth or being weak has improved. More specifically, in 2000 it was 8.9% less common for a child to be underweight compared to rates in the 1970s.[15] Conversely, between the years of 1970 and 1977, the prevalence of a children being overweight increased.[15] Similarly, in 2016 22.4% of school-aged children and adolescents aged 5 to 19 years were overweight.[15]

Women

From 1980 to 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) measured females malnutrition based on body mass index (BMI).[15] BMI is used to identify if an individual is normal weight, overweight or underweight.[15] From 1980 to 2016, the percentage of females who were underweight stayed at 8%, indicative of the static relationship and trend.[15] From 1980 to 2010, the percentage of females who were overweight increased from 25% to 33.6%.[14] WHO indicates that being overweight is a "major determinant of many non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, coronary heart diseases and stroke," along with many other health consequences.[16] The percentage of females who are overweight has, however, decreased from 33.6% to 27.4% from 2010 to 2016.[15] Conversely, the percentage of females who are obese has increased steadily from 2.5% to 6.1% from 1990 to 2016.[15] Obesity, as indicated by the WHO, can be mitigated through lifestyle changes.[16]

Common health issues

Dengue Fever

Climatic characteristics such as high temperatures and high humidity facilitate the transmission of dengue virus by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.[17] Owing to its tropical climate, Singapore is a highly-endemic area for dengue, and experiences 20–330 cases per 100,000 people each year, depending on the severity of outbreaks, with higher rates of transmission in the September to February rainy season.[18] The economic burden of this disease is significant, costing Singapore between 850 million and 1.15 billion USD between 2000 and 2010.[19]

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne disease, transmitted primarily by the species Aedes aegypti.[18] Transmission of the dengue virus occurs through the bite of the infected insect.[18] Dengue fever varies in clinical presentation. Many cases of dengue virus infection are asymptomatic, but headaches, high fevers, pain behind the eyes, muscle, joint and bone pain, and a skin rash with red spots within 4 to 7 days of being infected may occur. In these cases, the World Health Organization (WHO) differentiates between undifferentiated febrile illness caused by dengue, dengue fever (DF), or dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF) including dengue shock syndrome (DSS). DHF, characterised by increased vascular permeability and blood plasma leakage, may result in death, especially in the case of DSS, where shock results from decreased intravascular pressure caused by this leakage of plasma.[20]

While intensive mosquito vector control historically limited dengue incidence in Singapore, since the 1980s, the nation has experienced dengue outbreaks occurring cyclically, with increasing severity, every 5–6 years. The most recent sustained major outbreak of dengue occurred in 2013 and 2014, reaching peaks of 842 cases in June 2013 and 891 cases in July 2014, the greatest weekly dengue incidence recorded in Singaporean history.[21]

Singapore's National Environment Agency (NEA) has incorporated the use of sophisticated machine learning techniques in dengue forecasting. The Environmental Health Institute (EHI) of the NEA uses a model incorporating Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) methods in predictive outbreak forecasting, integrating population, meteorological, and vector surveillance data-based variables with epidemiological case report data collected through the Singaporean Ministry of Health and updated weekly to produce nationwide forecasts up to 3 months in advance.[22] The team's model successfully predicted outbreak patterns during the major dengue outbreak of 2013, forecasting a peak count of 863 dengue cases in the 26th week of 2013 (compared to the actual peak of 842 dengue cases, during the 25th week of 2013.) This prediction enabled better planning of resource and medical care allocation, including an early launch of a government-led public health education campaign two months earlier than scheduled to more effectively preempt the outbreak.[19]

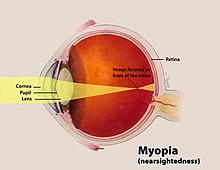

Myopia

Singapore is believed to have the highest prevalence of myopia in children worldwide.[23] More specifically, about "65% of children aged 12 in Singapore are myopic".[23] Myopia is a vision problem, affecting an individual's ability to see distant objects.[24] The major causes are still unclear. However, near work activities such as staring at a screen or reading a book are said to worsen the condition.[24]

Environmental impacts on health issues

Haze

Annually from May to October, Singapore experiences a smoke haze which can cause or worsen pre-existing health issues.[25] The haze is largely caused by, "winds bringing in tiny particles of ash," from the burning of forestry in Indonesia, the neighbouring country.[25] A person's likelihood of developing viral and bacterial infections is increased by breathing in an excess of these particles.[25] Additionally, individuals may experience irritation of the eyes, nose and throat if exposed to an excess amount of the haze.[25] However, in most cases these aforementioned health issues will resolve on their own.[25] The haze can also perpetuates existing heart and lung conditions, such as asthma.[26]

Air Pollution

Compared to most cities in Asia, Singapore's levels of air pollution are rather lower.[27] Singapore has experienced rapid urbanisation and industrialisation over the years.[27] Thus, "the main sources of air pollution in Singapore are emissions from the industries and motor vehicles".[27] The National Environment Agency has indicated that the most concerning air pollutants are particulate matter, carbon monoxide, ozone nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide.[27] Continuous exposure to these air pollutants can "cause respiratory symptoms and aggravate existing heart or lung disease".[28]

See also

References

- ^ Autism Therapy Treatment Centre Singapore | Autismstep , "Autismstep: Mortality", based on 2018 data.

- ^ Britnell, Mark (2015). In Search of the Perfect Health System. London: Palgrave. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-137-49661-4.

- ^ World Health Organization, "World Health Statistics 2007: Mortality", based on 2005 data.

- ^ Lim, Stephen; et, al. "Measuring human capital: a systematic analysis of 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016". Lancet. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ "Total Fertility Rate". Department of Statistics, Singapore. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Mortality rate, infant (per 1,000 live births) | Data". World Bank. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Births and Fertility – Latest Data". Department of Statistics, Singapore. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Death and Life Expectancy – Latest Data". Department of Statistics, Singapore. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Death and Life Expectancy". Department of Statistics, Singapore.

- ^ "China Life expectancy, 1950-2017 - knoema.com". Knoema. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade & Industry, Republic of Singapore (2017). "Population Trends,2017" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Chart of the Day: Old age dependency ratio on the rise in Singapore". Singapore Business Review. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Old-Age Support Ratio". Department of Statistics, Singapore. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ a b c "Malnutrition". healthhub.sg. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Nutrition Landscape Information System: Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLIS) Country Profile". World Health Organization. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Nutrition Landscape Information System: Help Content". World Health Organization. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Thu, H. M.; Aye, K. M.; Thein, S. (1998). "The effect of temperature and humidity on dengue virus propagation in Aedes aegypti mosquitos". The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 29 (2): 280–284. ISSN 0125-1562. PMID 9886113.

- ^ a b c "Singapore: Dengue | IAMAT". www.iamat.org. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ a b Shi, Yuan; Liu, Xu; Kok, Suet-Yheng; Rajarethinam, Jayanthi; Liang, Shaohong; Yap, Grace; Chong, Chee-Seng; Lee, Kim-Sung; Tan, Sharon S. Y. (2016). "Three-Month Real-Time Dengue Forecast Models: An Early Warning System for Outbreak Alerts and Policy Decision Support in Singapore". Environmental Health Perspectives. 124 (9): 1369–1375. doi:10.1289/ehp.1509981. ISSN 1552-9924. PMC 5010413. PMID 26662617.

- ^ Comprehensive guidelines for prevention and control of dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia (Rev. and expanded. ed.). New Delhi, India: World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. 2011. ISBN 978-92-9022-394-8. OCLC 711042340.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Hapuarachchi, Hapuarachchige Chanditha; Koo, Carmen; Rajarethinam, Jayanthi; Chong, Chee-Seng; Lin, Cui; Yap, Grace; Liu, Lilac; Lai, Yee-Ling; Ooi, Peng Lim (2016). "Epidemic resurgence of dengue fever in Singapore in 2013–2014: A virological and entomological perspective". BMC Infectious Diseases. 16: 300. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1606-z. ISSN 1471-2334. PMC 4912763. PMID 27316694.

- ^ Seltenrich, Nate (2016). "Singapore Success: New Model Helps Forecast Dengue Outbreaks". Environmental Health Perspectives. 124 (9): A167. doi:10.1289/ehp.124-A167. ISSN 1552-9924. PMC 5010405. PMID 27581656.

- ^ a b "Singapore achieves Breakthrough in Reducing prevalence of Myopia by almost 5%". Health Promotion Board. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Myopia—A World We Don't Want for Our Kids". healthhub.sg. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "ow to Protect Yourself From the Haze in Singapore – HealthXchange". healthxchange.sg. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Asthma". healthhub.sg. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Air Quality". nea.gov.sg. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Impact of Haze on health". healthhub.sg. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

External links

- [1]

- Dengue and severe dengue

- [2] Archived 27 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Air Quality

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !