Rise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2016) |

| History of the Ottoman Empire |

| Social structure |

|---|

| Court and aristocracy |

| Ethnoreligious communities |

| Rise of nationalism |

| Classes |

The rise of the Western notion of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire[1] eventually caused the breakdown of the Ottoman millet system. The concept of nationhood, which was different from the preceding religious community concept of the millet system, was a key factor in the decline of the Ottoman Empire.

Background

In the Ottoman Empire, the Islamic faith was the official religion, with members holding all rights, as opposed to Non-Muslims, who were restricted.[2] Non-Muslim (dhimmi) ethno-religious[3] legal groups were identified as different millets, which means "nations".[2]

Ideas of nationalism emerged in Europe in the 19th century at a time when most of the Balkans were still under Ottoman rule. The Christian peoples of the Ottoman Empire, starting with Serbs and Greeks, but later spreading to Montenegrins and Bulgarians, began to demand autonomy in a series of armed revolts beginning with the Serbian Revolution (1804–17) and the Greek War of Independence (1821–29),[1] which established the Principality of Serbia and Hellenic Republic.[4] The first revolt in the Ottoman Empire fought under a nationalist ideology was the Serbian Revolution.[5] Later the Principality of Montenegro was established through the Montenegrin secularization and the Battle of Grahovac. The Principality of Bulgaria was established through the process of the Bulgarian National Revival, and the subsequent National awakening of Bulgaria, establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate, the April Uprising of 1876, and the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878).

The radical elements of the Young Turk movement in the early 20th century had grown disillusioned with what they perceived to be the failures of 19th-century Ottoman reformers,[1] who had not managed to stop the advance of European expansionism or the spread of nationalist movements in the Balkans. These sentiments were shared by the Kemalists. These groups decided to abandon the idea of Ittihad-i anasır ("Unity of the Ethnic Elements") that had been a fundamental principle of the reform generation, and take up instead the mantle of Turkish nationalism.[6]

Michael Hechter argues that the rise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire was the result of a backlash against Ottoman attempts to institute more direct and central forms of rule over populations which had previously had greater autonomy.[7]

Albanians

The 1877–78 Russo-Turkish War dealt a decisive blow to Ottoman power in the Balkan Peninsula, leaving the empire with only a precarious hold on Macedonia and the Albanian-populated lands. The Albanians' fear that the lands they inhabited would be partitioned among Montenegro, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece fueled the rise of Albanian nationalism. The Albanians wanted to affirm their Albanian nationality. The first postwar treaty, the abortive Treaty of San Stefano signed on March 3, 1878, assigned Albanian-populated lands to Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria. The Albanian movements had mainly been against taxes and central policies.[8] However, with the Treaty of San Stefano the movements became nationalistic. Austria-Hungary and the United Kingdom blocked the arrangement because it awarded Russia a predominant position in the Balkans and thereby upset the European balance of power. A peace conference to settle the dispute was held later in the year in Berlin, known as the Congress of Berlin.[8] A memorandum in the name of all Albanians was addressed to Lord Beaconsfield from Great Britain not even a week after the opening of the Congress of Berlin.[8] The reason why this memorandum was addressed to Great Britain was that the Albanians could not represent themselves, because they were still under Ottoman rule.[8] Another reason why Great Britain was in the best position to represent the Albanians, because Great Britain did not want to replace the Turkish Empire.[8] This memorandum had to define the land belonging to the Albanians and create an independent Albania.[8]

Arabs

Arab nationalism is a nationalist ideology that arose in the 20th century[9] It is based on the premise that nations from Morocco to the Arabian peninsula are united by their common linguistic, cultural and historical heritage.[9] Pan-Arabism is a related concept, which calls for the creation of a single Arab state, but not all Arab nationalists are also Pan-Arabists. In the 19th century in response to Western influences, a radical change took shape. Conflict erupted between Muslims and Christians in different parts of the empire in a challenge to that hierarchy. This marked the beginning of the tensions which have to a large extent inspired the nationalist and religious rhetoric in the empire's successor states throughout the 20th century.[10][11]

A sentiment of Arab tribal solidarity (asabiyya), underlined by claims of Arab tribal descent and the continuance of classical Arabic exemplified in the Qur'an, preserved, from the rise of Islam, a vague sense of Arab identity among Arabs. However, this phenomenon had no political manifestations (the 18th-century Wahhabi movement in Arabia was a religious-tribal movement, and the term "Arab" was used mainly to describe the inhabitants of Arabia and nomads) until the late 19th century, when the revival of Arabic literature was followed in the Syrian provinces of the Ottoman Empire in Syria and Lebanon by a discussion of Arab cultural identity and demands for greater autonomy for Syria. This movement, however, was confined almost exclusively to certain Christian Arabs, and had little support. After the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 in Turkey, these demands were taken up by some Syrian and Lebanese Muslim Arabs and various public or secret societies (the Beirut Reform Society led by Salim Ali Salam, 1912; the Ottoman Administrative Decentralization Party, 1912; al-Qahtaniyya, 1909; al-Fatat, 1911; and al-Ahd, 1912) were formed to advance demands ranging from autonomy to independence for the Ottoman Arab provinces.[12] Members of some of these groups came together at the request of al-Fatat to form the Arab Congress of 1913 in Paris, where desired reforms were discussed.

Armenians

Until the Tanzimat reforms were established, the Armenian millet was under the supervision of an Ethnarch ('national' leader), the Armenian Apostolic Church. The Armenian millet had a great deal of power - they set their own laws and collected and distributed their own taxes. During the Tanzimat period, a series of constitutional reforms provided a limited modernization of the Ottoman Empire also to the Armenians. In 1856, the "Reform Edict" promised equality for all Ottoman citizens irrespective of their ethnicity and confession, widening the scope of the 1839 Edict of Gülhane.

To deal with the Armenian national awakening, the Ottomans gradually gave more rights to its Armenian and other Christian citizens. In 1863 the Armenian National Constitution was the Ottoman-approved form of the "Code of Regulations" composed of 150 articles drafted by the "Armenian intelligentsia", which defined the powers of the Armenian Patriarch and the newly formed "Armenian National Assembly".[13] The reformist period peaked with the Ottoman constitution of 1876, written by members of the Young Ottomans, which was promulgated on 23 November 1876. It established freedom of belief and equality of all citizens before law. The Armenian National Assembly formed a "governance in governance" to eliminate the aristocratic dominance of the Armenian nobility by the development of the political strata among the Armenian society.[14]

Assyrians

Under the millet system of the Ottoman Empire, each sect of the Assyrian nation was represented by their respective patriarch. Under the Church of the East sect, the patriarch was the temporal leader of the millet which then had a number of "maliks" beneath the patriarch who would govern each of their own tribes.

The rise of modern Assyrian nationalism began with intellectuals such as Ashur Yousif, Naum Faiq and Farid Nazha who pushed for a united Assyrian nation comprising the Jacobite, Nestorian and Chaldean sects.[15]

Bosniaks

The Ottoman Sultans attempted to implement various economic reforms in the early 19th century in order to address the grave issues mostly caused by the border wars. The reforms, however, were usually met with resistance by the military captaincies of Bosnia. The most famous of these insurrections was the one by captain Husein Gradaščević in 1831. Gradaščević felt that giving autonomy to the eastern lands of Serbia, Greece and Albania would weaken the position of the Bosnian state, and the Bosniak peoples.[16] The situation worsened when the Ottomans took 2 Bosnian provinces and gave them to Serbia, as a friendly gift to the Serbs.[17][18][19] Outraged, Gradaščević raised a full-scale rebellion in the province, joined by thousands of native Bosnian soldiers who believed in the captain's prudence and courage, calling him Zmaj od Bosne (dragon of Bosnia). Despite winning several notable victories, notably at the famous Battle of Kosovo, the rebels were eventually defeated in a battle near Sarajevo in 1832 after Herzegovinian nobility which supported the Sultan, broke stalemate. Husein-kapetan was banned from ever entering the country again, and was eventually poisoned in Istanbul. Bosnia and Herzegovina would remain part of the Ottoman Empire until 1878. Before it was formally occupied by Austria-Hungary, the region was de facto independent for several months. The aim of the movement of Husein Gradaščević was to keep status quo in Bosnia. Bosniak nationalism in the modern sense would emerge under the rule of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[20]

Bulgarians

The rise of national conscience in Bulgaria led to the Bulgarian revival movement. Unlike Greece and Serbia, the nationalist movement in Bulgaria did not concentrate initially on armed resistance against the Ottoman Empire but on peaceful struggle for cultural and religious autonomy, the result of which was the establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate on February 28, 1870. A large-scale armed struggle movement started to develop as late as the beginning of the 1870s with the establishment of the Internal Revolutionary Organisation and the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee, as well as the active involvement of Vasil Levski in both organisations. The struggle reached its peak with the April Uprising which broke out in April 1876 in several Bulgarian districts in Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia. The harsh suppression of the uprising and the atrocities committed against the civilian population increased the Bulgarian desire for independence. They also caused a tremendous indignation in Europe, where they became known as the Bulgarian Horrors.[21] Consequently, at the 1876–1877 Constantinople Conference, also known as the Shipyard Conference, European statesmen proposed a series of reforms. Russia threatened the Sultan with Cyprus if he did not agree to the conditions. However, the sultan refused to implement them, as the terms were very harsh, and Russia declared war. During the war Bulgarian volunteer forces (in Bulgarian опълченци) fought alongside the Russian army. They earned particular distinction in the battle for the Shipka Pass. Upon the end of the war Russia and Turkey signed the Treaty of San Stefano, which granted Bulgaria autonomy from the Sultan. The Treaty of Berlin, signed in 1878, essentially nullified the Treaty of San Stefano. Instead, Bulgaria was divided into two provinces. The northern province was granted political autonomy, and was called Principality of Bulgaria, while the southern province of Eastern Rumelia was placed under direct political and military control of the Sultan.[22]

Greeks

With the decline of the Eastern Roman Empire, the pre-eminent role of Greek culture, literature and language became more apparent. From the 13th century onwards, with the territorial reduction of the Empire to strictly Greek-speaking areas, the old multiethnic tradition, already weakened, gave way to a self-consciously national Greek consciousness, and a greater interest in Hellenic culture evolved. Byzantines began to refer to themselves not just as Romans (Rhomaioi) but as Greeks (Hellenes). With the political extinction of the Empire, it was the Greek Orthodox Church, and the Greek-speaking communities in the areas of Greek colonization and emigration, that continued to cultivate this identity, through schooling as well as the ideology of a Byzantine imperial heritage rooted both in the classical Greek past and in the Roman Empire.[23]

The position of educated and privileged Greeks within the Ottoman Empire improved in the 17th and 18th centuries. As the empire became more settled, and began to feel its increasing backwardness in relation to the European powers, it increasingly recruited Greeks who had the kind of academic, administrative, technical and financial skills which the larger Ottoman population lacked. Greeks made up the majority of the Empire's translators, financiers, doctors and scholars. From the late 1600s, Greeks began to fill some of the highest offices of the Ottoman state. The Phanariotes, a class of wealthy Greeks who lived in the Phanar district of Constantinople, became increasingly powerful. Their travels to other parts of Western Europe, as merchants or diplomats, brought them into contact with advanced ideas of the Enlightenment notably liberalism, radicalism and nationalism, and it was among the Phanariotes that the modern Greek nationalist movement matured. However, the dominant form of Greek nationalism (that later developed into the Megali Idea) was a messianic ideology of imperial Byzantine restoration, that specifically looked down upon Frankish culture, and enjoyed the patronage of the Orthodox Church.[24]

Ideas of nationalism began to develop in Europe long before they reached the Ottoman Empire. Some of the first effects nationalism had on the Ottomans had much to do with the Greek War of Independence. The war began as an uprising against the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. At the time, Mehmet Ali, a former Albanian mercenary, was ruling Egypt quite successfully. One of his biggest projects was creating a modern army of conscripted peasants. The Sultan commanded him to lead his army to Greece and put a stop to these uprisings. At the time, nationalism had become an established concept in Europe and certain Greek intellectuals began to embrace the idea of a purely Greek state. Most of Europe greatly supported this notion, partly because ideas of Ancient Greece's mythology were being greatly romanticized in the Western world. Though the Greece at the time of the revolution looked very little like the European view, most supported it blindly based on this notion.

Mehmet Ali had his own motives for agreeing to invade Greece. The Sultan promised Ali that he would make him Governor of Crete, which would increase Ali's status. Ali's army had considerable success in putting down the Christian revolts at first, however before too long the European Powers intervened. They endorsed Greek nationalism and pushed both Ali's army and the rest of the Ottoman forces out of Greece.

The instance of Greek Nationalism was a major factor in introducing the concept to the Ottomans. Because of their failure in Greece, the Ottomans were forced to acknowledge the changes taking place in the West, in favor of Nationalism. The result would be the beginning of a defensive developmentalism period of Ottoman history in which they attempted to modernize to avoid the Empire falling to foreign powers. The idea of nationalism that develops out of this is called Ottomanism, and would result in many political, legal, and social changes in the Empire.

- In 1821 the Greek revolution, striving to create an independent Greece, broke out on Romanian ground, briefly supported by the princes of Moldavia and Muntenia.

- A secret Greek nationalist organization called the Friendly Society (Filiki Eteria) was formed in Odesa during 1814. On March 25 (now Greek Independence Day) 1821 of the Julian Calendar/6 April 1821 of the Gregorian Calendar the Orthodox Metropolitan Germanos of Patras proclaimed the national uprising.[25][26] Simultaneous risings were planned across Greece, including in Macedonia, Crete and Cyprus. The revolt began in March 1821 when Alexandros Ypsilantis, the leader of the Etairists, crossed the Prut River into Turkish-held Moldavia with a small force of troops. With the initial advantage of surprise, the Greeks succeeded in liberating the Peloponnese and some other areas.

Kurds

The system of administration introduced by Idris remained unchanged until the close of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29. But the Kurds, owing to the remoteness of their country from the capital and the decline of Ottoman Empire, had greatly increased in influence and power, and had spread westwards over the country as far as Ankara.[citation needed]

After the war the Kurds attempted to free themselves from Ottoman control [citation needed], and in 1834, after the Bedirkhan clan uprising, it became necessary to reduce them to subjection. This was done by Reshid Pasha. The principal towns were strongly garrisoned, and many of the Kurd beys were replaced by Turkish governors. A rising under Bedr Khan Bey in 1843 was firmly repressed, and after the Crimean War the Turks strengthened their hold on the country.

The Ottoman Empire, faced with challenges from their European counterparts, started a centralisation campaign, intending to have more direct authority over resources and population.[27] After beating Kurdish autonomy, namely the principality of Bohtan, also known as Cizira Bohtan, in present-day Cizre, the Sultan had hoped that the region would now be more manageable and under Ottoman control. However, the opposite was true. The Empire did not gain any authority because of a lack of local institutions and not actively creating them.[28] Instead, by removing the Mirs and thus the local power structure, the area became more chaotic. Local tribes sought to exploit the situation and advance their own interests.[27] Unable to directly confront Istanbul, the emergence of the Russian Empire’s advances on the Anatolian plateau posed an opportunity.

By this time, the Kurdish revolts in the Ottoman Empire were still not seen as a part of nationalism, but rather as attempts of local leaders to increase influence.[29] This mostly changed during Şêx Ubeydullah's and Abdurezzak's involvements in the late eighteenth-century Russo-Turkish conflicts.[29]

The Sultan attempted to assert his influence in the Kurdish areas by installing the Hamidiye regiments. The commanders were selected on the basis of loyalty to the Sultan, and were awarded with several privileges, mainly the right to form militias, and gifted these tribal leaders with titles, arms and money in the hopes that this would lead to a new class of ruling elites.[30] The rise of intellectualism and activism amongst the population of Kurds brought critique to this new elitist class. Some of the most well-known opponents of Sultan Abdulhamid II were descendants of the Mir of Bohtan, claiming that these policies were stagnating Kurdish progress and well-being.[31] They called for modern educational reforms. The Naqshbandi Şêx Bediüzzaman Said-i Kurdi even travelled to Istanbul to address the need for education in Kurdish areas to the Sultan.

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 was followed by the attempt of Sheikh Obaidullah in 1880–1881 to found an independent Kurd principality under the protection of the Ottoman Empire.[32] The attempt, at first encouraged by the Porte, as a reply to the projected creation of an Armenian state under the suzerainty of Russia, collapsed after Obaidullah's raid into Persia, when various circumstances led the central government to reassert its supreme authority. Until the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829 there had been little hostile feeling between the Kurds and the Armenians, and as late as 1877–1878 the mountaineers of both races had co-existed fairly well together.

In 1891 the activity of the Armenian Committees induced the Porte to strengthen the position of the Kurds by raising a body of Kurdish irregular cavalry,[33] which was well-armed and called Hamidieh after the Sultan Abd-ul-Hamid II. Minor disturbances constantly occurred, and were soon followed by the massacre of Armenians at Sasun and other places, 1894–1896, in which the Kurds took an active part. Some of the Kurds, like the nationalist Armenians, aimed to establish a Kurdish country.

A major development for Kurdish nationalism in the late Ottoman Empire was the foundation of the "Kurdistan" newspaper in 1898, based in Cairo. With the aim of spreading Kurdish cultural and nationalist ideas, seeking to unify Kurds and foster a national consciousness. Additionally, as a result of the successes of the Young Turk movement in 1908, many minorities in the Empire were, initially, allowed to create their own political organizations. Some notable Kurdish organizations were the Kurdish Society for Cooperation and Progress (KTTC), Hewa, and the Society for the Rise of Kurdistan (SAK).[34] These groups fostered the growth of an educated elite for Kurdish nationalism. However, the majority of the Kurds did not support these aspirations, as many tribal leaders saw it as a threat to their own authority.[35]

Jews

Early Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II established the Hakham Bashi, as the Rabbi of a particular region, with the Hakham Bashi of Constantinople being the most powerful.[36]

In 1492, Sultan Bayezeid II ordered governors of Ottoman provinces to accept Jewish immigration and to do so cordially. This order was in response to the Alhambra Decree, that ordered for the expulsion of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula. This resulted in many Jewish refugees, and due to the high level of freedom enjoyed by Ottoman Jews, many looked to immigrate to Ottoman territory. In 1492 alone, roughly 60,000 Jews arrived in the Ottoman Empire.[37]

The Ottomans took control of Palestine from the Mamluk Empire in 1516, though during this time, there was no entity called "Palestine." There was a continuous Jewish population in the area due to the religious significance and significant holy sites to all Abrahamic religions.[38] [39] Aliyah, or Jewish immigration to Palestine, accelerated with the First Aliyah in 1882, largely triggered by pogroms in Tsarist Russia.[40]

Zionist Movement

While the Ottoman Empire became a safe space for Jews, parts of Europe saw increased violence and anti-semitism against Jews. Violent uprisings against Jews took place all over Eastern Europe in the Late 19th century, and the civil rights of Jews were extremely limited.[41]

Zionism is an international political movement; although started outside the Ottoman Empire, Zionism regards the Jews as a national entity and seeks to preserve that entity. This has primarily focused on the creation of a homeland for the Jewish People in the Promised Land, and (having achieved this goal) continues as support for the modern state of Israel.

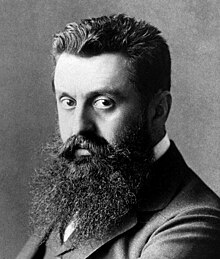

Although its origins are earlier, the movement became better organized and more closely linked with the imperial powers of the day following the involvement of the late 19th century Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist Theodor Herzl, who is often credited as the father of the Zionist movement. Herzl He formed the World Zionist Organization and called for the First Zionist Congress in 1897.[42] The movement was eventually successful in establishing Israel in 1948, as the world's first and only modern Jewish State. Described as a "diaspora nationalism,"[43] its proponents regard it as a national liberation movement whose aim is the self-determination of the Jewish people.

The objective of Zionism grew into the desire to form a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Early in the movement, there were many competing theories regarding the best avenue to achieve Jewish autonomy. The Jewish Territorial Organization represented a popular proposal. The organization supported finding a location, besides Palestine, for Jewish settlement.[44]

Non-territorial autonomy was another popular theory. This was a principle that allowed for groups to self govern themselves without their own state. The Millet system in the Ottoman Empire allowed for this and was used by Orthodox Christians, Armenians, and even Jews. This gave Jews significant legislative and governing powers in the Ottoman Empire. Jews weren't on the same social hierarchy as Muslims in the Ottoman Empire, however, they still enjoyed many protections as they were considered people of the book. This relative autonomy allowed for the formation of many Jewish ideas and practices, increasing the common identity.[45]

As the goal of the Zionist movement grew, many Jews already living in the Ottoman Empire wanted to leverage their relative autonomy into settlement of Palestine. Eventually, the form of Zionism with Palestine as the intended homeland prevailed among the competing theories. Palestine was chosen due to the religious and historical significance of the region. Also, the declining power and financial struggles of the Ottoman Empire were seen as an opportunity.[46] Wealthy and powerful Jews began to put their ideas into action.[47]

Jewish Settling of Palestine

See Also: First Aliyah, Second Aliyah

Herzl founded the Jewish-Ottoman Land Company. Its objective was to acquire land in Palestine, for the settlement of Jews, through political channels with the Ottoman Empire. Herzl repeatedly visited Istanbul and engaged in negotiations and meetings with Ottoman officials. In 1901, Herzl was able to have a meeting with Sultan Abdul Hamid and insinuated that he had access to Jewish credit and that he could help the Ottoman Empire pay off debt. The company was initially successful, however, it eventually faced opposition from Arabs and the government.[48] These negotiations are incredibly noteworthy considering Herzl was not a government official of any kind; he was just a private citizen.

The Jewish National Fund functioned similarly. It was a fund directed for land purchasing in Palestine. By 1921, around 25,000 acres had been purchased by the Fund in Palestine. Immigration of Jewish people into Palestine in 4 periods or Aliyahs.[49] The first took place between 1881 and 1903, resulting in around 25,000 immigrating. The second took place between 1904 and 1914, resulting in around 35,000 Jews immigrating.[50]

The increased Jewish population and Jewish land in Israel furthered the formation of a Jewish national identity. As the population and property owned by Jews increased in Palestine, support and backing continued to grow. However, so did tensions with other groups, especially Muslim Arabs. Arabs saw the massive Jewish immigration and financial interest in the region as threatening.[51]

Revival of Hebrew

Part of this movement included the revival of the Hebrew Language. Hebrew had been spoken traditionally by the Israelites but was estimated to die out at as a spoken language around 200 CE. However, Jewish people continued to use the language for writing and prayer purposes. Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, an early member of the Zionist movement, immigrated to Ottoman controlled Palestine in 1881. Ben-Yehuda believed that the modern development of Hebrew wasn't feasible unless it was linked to Zionism. Hebrew quickly was picked up among the Jewish community in Palestine and became a part of the Jewish identity.[52][53]

Outside of Palestine

Areas in the Ottoman Empire, besides Palestine, contained significant Jewish presence. Iraq, Tunisia, Turkey, Greece, and Egypt all had large and formidable Jewish populations. Most of these populations could trace their lineage in these areas back thousands of years to biblical times.

Turkey

Bursa was one of the first cities with a Jewish population conquered by the Ottomans when it was conquered in 1324. The Jewish inhabitants helped the Ottoman army, and they were allowed to return to the city. The Ottomans then granted the Jewish people a certain level of autonomy. This early interaction helped set the standard for Ottoman-Jewish interaction throughout the remainder of Ottoman rule.[54]

Istanbul quickly became a cultural center for Jews in the Near East. Jews were able to prosper in many high-skill fields, such as the medical field. This elevated social status resulted in even more freedom and the ability to solidify Jewish identities.

Iraq

The Siege of Baghdad in 1258 by the Mongols led to the ruin of Baghdad and end of the Abbasid Dynasty. Baghdad was left depopulated and many surviving residents left and moved elsewhere.[55] In 1534, the Ottomans captured Baghdad from the Persians. Baghdad had not seen a strong Jewish population since before the Mongol raid.[56] Many Jewish communities existed in small, isolated areas around Mesopotamia at the time. However, a resurgence in the Jewish population was seen in Baghdad after the Ottoman capture. Jews from Kurdistan, Syria, and Persia began to migrate back into Baghdad. Zvi Yehuda refers to this as the "new Babylonian Diaspora." Jewish population and strength continued to grow in Iraq in the following centuries. In 1900, around 50,000 Jews lived in Baghdad, making up nearly a quarter of its population. Jews played very important roles in Iraqi life and culture. The first Minister of Finance in Iraq, Sassoon Eskell, was even Jewish.[57] Baghdad and other Iraqi cities were able to function as a Jewish cultural and religious hub throughout Ottoman rule.[58] This freedom and autonomy helped for the development of a strong national Jewish ideology.

Syria

Jewish roots in Syria can date back to Biblical times, and strong Jewish communities have been present in the region since Roman rule. An influx of Jewish settlers came to Syria after the Alhambra Decree in 1492.[59] Aleppo and Damascus were two main centers. Qamishli, a Kurdish town, also became a popular destination. The Aleppo Codex, a manuscript of the Hebrew Bible written in Tiberias, was kept at the Central Synagogue of Aleppo for nearly 600 years of Ottoman Rule. The synagogue was believed by some to have initially been constructed around 1000 BCE by Joab ben Zeruiah, the nephew and General of King David's army.[60] Inscriptions in the Synagogue date back to 834 CE. The heavy migration of Spanish and Italian Jews into Syria resulted in tension between Jewish groups already in the country. This tension was caused by differences in practices and languages. Many of the new residents spoke different languages, especially the Spanish. However, as generations passed, the descendants of Spanish and Italian settlers began to use these languages less and less. Jews continued to rise in status and power in Syria during Ottoman rule. Many Christians held angst against the rapidly increasing Jewish class causing poor relations between the two groups.[61][better source needed]

Greece

Salonika, or Thessaloniki, was a major Jewish center known as the "Jerusalem of the Balkans," "Mother of Israel" and a "Sephardic Metropolis," a site of Jewish refuge for Sephardim and Ashkenazim alike.[62][63][64] Many Sephardic Jews came to Thessaloniki after their expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula in 1492. The vast Sephardic immigration allowed Thessaloniki to be a hub for diverse Jewish ideas. This large presence and advancement of Jews served as a strong national symbol of Jewish prosperity.[65] Jews in Thessaloniki enjoyed a strategic and important location as a port in the Trans-Mediterranean trade network. 19th and 20th century Thessaloniki is commonly referred to as the "Golden Age", especially for its Jewish inhabitants. The success and prosperity enjoyed by Thessaloniki began to be used as an example of a Jewish state and proof that the concept would succeed.[citation needed]

Synagogues

An important aspect of forming a national Jewish identity, especially based on religion, was the construction of Synagogues. The Jewish houses of worship allowed Jews to congregate in worship and share their ideas and beliefs. Many synagogues were constructed or rebuilt during Ottoman rule. The Bet Yaakov Synagogue was constructed in Istanbul in 1878. The Ahrida Synagogue is an extremely notable one built in Istanbul in the 1430s. It is located in the Balat area of Istanbul, a formerly vibrant Jewish area. These synagogues were able to function as the cultural center within their own communities.[66]

Macedonians

The national awakening of the Macedonians can be said to have begun in the late 19th century; this is the time of the first expressions of ethnic nationalism by limited groups of intellectuals in Belgrade, Sofia,[67][68] Thessaloniki and St. Petersburg.[69] The "Macedonian Question" became especially prominent after the Balkan wars in 1912–1913 and the subsequent division of the Ottoman Macedonia between three neighboring Christian states, followed by tensions between them over its possession. In order to legitimize their claims, each of these countries tried to 'persuade' the population into allegiance. The Macedonist ideas grew in significance after the First World War, both in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and among the left-leaning diaspora in the Kingdom of Bulgaria, and were endorsed by the Comintern.

Montenegrins

The Principality was formed on 13 March 1852 when Danilo I Petrović-Njegoš, formerly known as Vladika Danilo II, decided to renounce to his ecclesiastical position as prince-bishop and married. With the first Montenegrin constitution being proclaimed in 1855, known as "Danilo's Code". After centuries of theocratic rule, this turned Montenegro into a secular principality.

Grand Voivode Mirko Petrović, elder brother of Danilo I, led a strong army of 7,500 and won a crucial battle against the Turks (army of between 7,000 and 13,000) at Grahovac on 1 May 1858. The Turkish forces were routed. This victory forced the Great Powers to officially demarcate the borders between Montenegro and Ottoman Turkey, de facto recognizing Montenegro's centuries-long independence.

Romanians

The Wallachian uprising of 1821 began as an anti-Phanariote revolt, which grew into an insurrection through the involvement of the Greek Filiki Eteria. Moldavia was occupied by Ypsilantis, while Wallachia was held by Tudor Vladimirescu. As the latter was incapable of maintaining discipline in his rebel army (the "Pandurs") and also was willing to compromise with the Ottomans, the Eteria had him arrested after the Ottoman army retook Bucharest without resistance. His army was disbanded and the rebellion suppressed after the Ottomans destroyed the Eterists in the Danubian Principalities. While unsuccessful in obtaining liberty, it ended the Phanariote era; Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II consented in 1822 to the nomination of two native boyars, Ioan Sturdza and Grigore IV Ghica as hospodars of Moldavia and Wallachia.

1848 saw rebellion in both Moldavia and Wallachia.

Serbs

The Serbian national movement represents one of the first examples of successful national resistance against the Ottoman rule.[70] It culminated in two mass uprisings at the beginning of the 19th century, leading to national liberation and establishment of the Principality of Serbia.[71] One of the main centers of this movement was the Sanjak of Smederevo ("Belgrade Pashaluk"),[72] which became the core of the reestablished Serbian national state.[73]

A number of factors contributed to its rise. Above all the nucleus of national identity was preserved in the form of the Serbian Orthodox Church which remained autonomous in one form or another throughout the period of Ottoman occupation.[72] Adherence to Orthodox Christianity is still considered an important factor in ethnic self-determination. The Serbian Church preserved links with the medieval Serbian past, keeping the idea of national liberation alive.[72]

The other group of factors stem from regional political events during the period of Ottoman rule, the 17th and 18th centuries in particular. The Austrian wars against the Ottoman Empire resulted in periods of Austrian rule in central Serbia (in 1718–39 and 1788–92), thus, the turn of the 19th century saw the relatively recent experience of European rule. Although the territory of northern Serbia had first reverted to Ottoman rule according to the Treaty of Belgrade, the region saw almost continuous conflict during the 18th century. As a result, the Ottomans never established a full feudal order in the Belgrade Pashaluk, and free peasants owning small plots of land constituted the majority of the population.[citation needed] This primarily worked through a direct relationship between the higher and the lower classes where the lower classes were more inclined to offer service in exchange for protection.[74] As the Ottoman never did inaugurate the full establishment of this system in the Belgrade Pashaluk, those people who were in lower classes, primarily consisting of peasants, were able to hold access and ownership to small shares of land, and these peasants made the majority of the population. Later on, Miloš Obrenović[75] attempted to take over more control by abusing his power and authority as more peasants lived and worked under Turkish lords rather than under Serbian ones.[76][77] Furthermore, most of the leaders of future armed rebellions earned valuable military knowledge serving in Austrian irregular troops, freikorps. The proximity of the Austrian border provided the opportunity of getting the needed military material. The Serbian leaders could also count on the financial and logistical support of fellow Serbs living in relative prosperity in the Austrian Empire.

The immediate cause for the start of the First Serbian Uprising (1804–13) was the mismanagement of the province by renegade Janissary troops (known as Dahije) who had seized power. While the Serbian population first rose up against the Dahije, their quick success fueled the desire for national liberation and led to a full-fledged war. Though unsuccessful, this rebellion paved the way for the Second Serbian Uprising of 1815, which eventually succeeded. Serbia became a center of resistance to Ottomans, actively or secretly supporting liberation movements in neighboring Serb-inhabited lands, especially Bosnia, Herzegovina and Macedonia, as well other Christian-inhabited lands, such as Greece. It resulted to Herzegovina uprising in 1875, and Serbian-Turkish wars (1876–1878). In 1903, Serbian Chetnik Organization was founded in aim to liberate Old Serbia (Kosovo and Macedonia), which was on territories of Kosovo Vilayet and Macedonian vilayets under Ottoman rule. The Serbian–Ottoman conflict culminated in the First Balkan War of 1912.

Turks

Pan-Turkism emerged with the Turanian Society founded in 1839 by Tatars. However, Turkish nationalism was developed much later in 1908 with the Turkish Society, which later expanded into the Turkish Hearth[78] and eventually expanded to include ideologies such as Pan-Turanism and Pan-Turkism. With the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the Turkish populations of the empire which were mostly expelled from the newly established states in the Balkans and the Caucasus formed a new national identity under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal along the Kemalist ideology.

Turkish revolutionaries were patriots of the Turkish national movement who rebelled against the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire by the Allies and the Ottoman government in the aftermath of the Armistice of Mudros, which ended the Ottoman Empire's participation in World War I; and against the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, which was signed by the Ottoman government and partitioned Anatolia among Allies and their supporters.

Turkish revolutionaries under the leadership of Atatürk fought during the Turkish War of Independence against the Allies supported by Armenians (First Republic of Armenia), Greeks (Greece) and the French Armenian Legion, accompanied by the Armenian militia during the Franco-Turkish War. Turkish revolutionaries rejected the Treaty of Sèvres and negotiated the Treaty of Lausanne, which recognized the independence of the Republic of Turkey and its absolute sovereignty over Eastern Thrace and Anatolia.

Role of women

The Ottoman reforms were enforced to fight the rise of nationalism from within the state and European expansion. The Ottoman state increasingly restricted women including women with a higher status.[79] Women were not allowed to move around and wear what they desired.[79] Therefore, the goals of the reforms stated in the Noble Edict of the Rose Chamber of 1839 and the Imperial Script Hatt-I Hümayun of 1856 were actually only focused on the equality of male subjects of the Sultan in the Ottoman Empire.[79]

However, in the late centuries of the Ottoman Empire, women became more included in debates on the future of the Ottoman Empire.[79] Gender relations started to be re-examined when women started to have a new role in society.[79] The focus on nationalism in the Ottoman Empire changed the whole structure of the Ottoman society. One of the priorities of the Ottoman Empire was the development of the military to prevent the rise of nationalism and to prevent the conquest of land belonging to the Ottoman Empire by Russia and Europe. Mobilization by men and women would strengthen the empire politically and economically.[79] Women were responsible for raising the new Ottoman generations.[79] Mothers were creating and maintaining cultural identity and this would support the modernization efforts.[79] Therefore, there was a demand for the improvement of women's education. The new role that women opened the way for women to assert their rights.[79] However, due to the many different ethno-religious communities within the Ottoman Empire there were many differences between communities of women.[79] The women tried to come in contact with each other to spread their ideas from one ethno-religious group to another through formal and informal ways of communication.[79] Educational institutions were spaces were information about the developments in other ethno-religious communities would be shared.[79]

Nevertheless, it is also fair to mention that women in the Ottoman Empire had acquired their own rights and freedoms, such as the capability to dance and stage protests,[80] they were essential for the national economy as they were able to run businesses and own property.[81] Women in the Ottoman Empire had active roles in the economy, as well as religious spheres, and were essential for social communication.[82]

In 1917, the Ottoman Law of Family Rights was part of the Ottoman reform.[83] Some women viewed this reform as a critical moment in time to improve women's rights.[83] However, this was difficult for feminists in the Ottoman Empire, because they did not want to question the role of Islam and did not want to change their own traditions in a period of nationalism.[83] The women strived for a legal reform in their favor, but the Ottoman Law of Family Rights would not change much in expanding women's rights. According to Sijjil records, women were active in Sharia courts as an attempt to change their roles and increase women's rights.[84] The Sharia courts gave women the opportunity to increase their agency.[84]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Roshwald, Aviel (2013). "Part II. The Emergence of Nationalism: Politics and Power – Nationalism in the Middle East, 1876–1945". In Breuilly, John (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Nationalism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 220–241. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199209194.013.0011. ISBN 9780191750304. Archived from the original on 2023-01-15. Retrieved 2022-12-17.

- ^ a b Antonello Biagini; Giovanna Motta (19 June 2014). Empires and Nations from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Century: Volume 1. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-1-4438-6193-9.

- ^ Cagaptay 2014, p. 70.

- ^ Stojanović 1968, p. 2.

- ^ M. Şükrü Hanioğlu (8 March 2010). A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-1-4008-2968-2.

- ^ Zürcher, Erik J. (2010). The Young Turk Legacy and Nation Building: From the Ottoman Empire to Atatürk's Turkey. I.B. Tauris. p. 60. ISBN 9781848852723. Archived from the original on 2023-04-22. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ Hechter, Michael (2001). Containing nationalism. Oxford University Press. pp. 71–77. ISBN 0-19-924751-X. OCLC 470549985. Archived from the original on 2021-06-22. Retrieved 2020-09-07.

- ^ a b c d e f Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian National Awakening 1878-1912. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 3–88.

- ^ a b Charles Smith, The Arab-Israeli Conflict, in International Relations in the Middle East by Louise Fawcett, p. 220.

- ^ Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Arab World, Bruce Masters, Cambridge

- ^ "Arab Nationalism". Archived from the original on 2009-11-01. Retrieved 2009-08-27.

- ^ Khalidi, Rashid; Anderson, Lisa; Muslih, Muhammad; Simon, Reeva S., eds. (December 1991). The Origins of Arab Nationalism. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-07435-3.

- ^ Richard G. (EDT) Hovannisian "The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times" p. 198

- ^ Ilber Ortayli, Tanzimattan Cumhuriyete Yerel Yönetim Gelenegi, Istanbul 1985, p. 73

- ^ "A Brief Study in the Palak Nationalism", by Dr. David Barsoum Perley LL.B.

- ^ Sućeska 1985, p. 81.

- ^ English translation: Leopold Ranke, A History of Serbia and the Serbian Revolution. Translated from the German by Mrs Alexander Kerr (London: John Murray, 1847)

- ^ "The Serbian Revolution and the Serbian State". Archived from the original on 2017-10-10. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- ^ L. S. Stavrianos, The Balkans since 1453 (London: Hurst and Co., 2000), p. 248–250.

- ^ Babuna, Aydın (1999). "Nationalism and the Bosnian Muslims". East European Quarterly. XXXIII (2): 214.

- ^ "National revolution (from Bulgaria)". 2006-05-21. Archived from the original on 2006-05-21. Retrieved 2022-12-19.

- ^ Lord Kinross, The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire, Morrow Quill Paperbacks (New York) 1977, p. 525.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Greece during the Byzantine period (c. AD 300–c. 1453) > Population and languages > Emerging Greek identity, 2008 ed.

- ^ Ροτζώκος Νίκος, Επανάσταση και εμφύλιος στο εικοσιένα, pages 131-137

- ^ McManners, John (2001). The Oxford illustrated history of Christianity. Oxford University Press. pp. 521–524. ISBN 0-19-285439-9.

The Greek uprising and the church. Bishop Germanos of old Patras blesses the Greek banner at the outset of the national revolt against the Turks on 25 March 1821. The solemnity of the scene was enhanced two decades later in this painting by T. Vryzakis….The fact that one of the Greek bishops, Germanos of Old Patras, had enthusiastically blessed the Greek uprising at the onset (25 March 1821) and had thereby helped to unleash a holy war, was not to gain the church a satisfactory, let alone a dominant, role in the new order of things.

- ^ "Greek Independence Day". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2015-05-03. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

The Greek revolt was precipitated on March 25, 1821, when Bishop Germanos of Patras raised the flag of revolution over the Monastery of Agia Lavra in the Peloponnese. The cry "Freedom or Death" became the motto of the revolution. The Greeks experienced early successes on the battlefield, including the capture of Athens in June 1822, but infighting ensued.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Michael A. (2017), "The Ends of Empire. Imperial Collapse and the Trajectory of Kurdish Nationalism", Regional Routes, Regional Roots? Cross-Border. Patterns of Human Mobility in Eurasia, Hokkaido Slavic-Eurasian Reserarch Center, pp. 31–48, retrieved 2024-05-23

- ^ Bruinessen, Martin van (1992). Agha, Shaikh and state: the social and political structures of Kurdistan. London: Zed Books. pp. 176–82. ISBN 978-1-85649-019-1.

- ^ a b Disney, Donald Bruce (1980-12-01). The Kurdish nationalist movement and external influences. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School.

- ^ Klein, Janet (2011). The Margins of Empire: Kurdish Militias in the Ottoman Tribal Zone (1 ed.). Stanford University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvqsf1v3. ISBN 978-0-8047-7570-0. JSTOR j.ctvqsf1v3.

- ^ Reynolds, Michael A. (2017), "The Ends of Empire. Imperial Collapse and the Trajectory of Kurdish Nationalism", Regional Routes, Regional Roots? Cross-Border. Patterns of Human Mobility in Eurasia, Hokkaido Slavic-Eurasian Reserarch Center, pp. 31–48, retrieved 2024-05-23

- ^ Betty Anderson, A History of the Modern Middle East: Rulers, Rebels, and Rogues (Stanford University Press, 2016).

- ^ "Kurbash - Encyclopedia".

- ^ Edmonds, C. J. (1957). "The Kurds of Iraq". Middle East Journal. 11 (1): 52–62. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4322870.

- ^ Eagleton, William, Jr (1963). The Kurdish republic of 1946. Oxford University Press. p. 6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "EHRI - Archives of the Chief Rabbinate (Sephardi community) in Istanbul". portal.ehri-project.eu. Archived from the original on 2023-04-08. Retrieved 2023-04-08.

- ^ hersh (2022-12-04). "The History of the Jews of Turkey". Aish.com. Archived from the original on 2022-12-08. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ Qafisheh, M. (2009-01-01), "II Nationality In Palestine Under The Ottoman Empire", The International Law Foundations of Palestinian Nationality, Brill | Nijhoff, pp. 25–44, doi:10.1163/ej.9789004169845.i-254.14, ISBN 978-90-04-18084-0, retrieved 2024-09-11

- ^ Zeitlin, Solomon (1947). "Jewish Rights in Palestine". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 38 (2): 119–134. doi:10.2307/1453037. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1453037. Archived from the original on 2023-04-08. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Reinkowski, Maurus (1999). "Late Ottoman Rule over Palestine: Its Evaluation in Arab, Turkish and Israeli Histories, 1970-90". Middle Eastern Studies. 35 (1): 66–97. doi:10.1080/00263209908701256. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 4283983.

- ^ Brustein, William I.; King, Ryan D. (2004). "Anti-Semitism in Europe before the Holocaust". International Political Science Review. 25 (1): 35–53. doi:10.1177/0192512104038166. ISSN 0192-5121. JSTOR 1601621. S2CID 145118126. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Cohn, Henry J. (1970). "Theodor Herzl's Conversion to Zionism". Jewish Social Studies. 32 (2): 101–110. ISSN 0021-6704. JSTOR 4466575. Archived from the original on 2018-08-08. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Ernest Gellner, 1983. Nations and Nationalism (First edition), p 107-108.

- ^ Weisbord, Robert G. (1968). "Israel Zangwill's Jewish Territorial Organization and the East African Zion". Jewish Social Studies. 30 (2): 89–108. ISSN 0021-6704. JSTOR 4466406. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Légaré, André; Suksi, Markku (2008). "Introduction: Rethinking the Forms of Autonomy at the Dawn of the 21st Century". International Journal on Minority and Group Rights. 15 (2/3): 143–155. doi:10.1163/157181108X332578. ISSN 1385-4879. JSTOR 24674988. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Lewis, Bernard (1958). "Some Reflections on the Decline of the Ottoman Empire". Studia Islamica (9): 111–127. doi:10.2307/1594978. ISSN 0585-5292. JSTOR 1594978. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Oke, Mim Kemal (1982). "The Ottoman Empire, Zionism, and the Question of Palestine (1880-1908)". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 14 (3): 329–341. doi:10.1017/S0020743800051965. ISSN 0020-7438. JSTOR 163676. S2CID 162661505. Archived from the original on 2022-11-02. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Khalidi, Walid (1993). "The Jewish-Ottoman Land Company: Herzl's Blueprint for the Colonization of Palestine". Journal of Palestine Studies. 22 (2): 30–47. doi:10.2307/2537267. ISSN 0377-919X. JSTOR 2537267. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Lehn, Walter (1974). "The Jewish National Fund". Journal of Palestine Studies. 3 (4): 74–96. doi:10.2307/2535450. ISSN 0377-919X. JSTOR 2535450. Archived from the original on 2023-03-09. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Lehmann, Sophia (1998). "Exodus and Homeland: The Representation of Israel in Saul Bellow's "To Jerusalem and Back" and Philip Roth's "Operation Shylock"". Religion & Literature. 30 (3): 77–96. ISSN 0888-3769. JSTOR 40059741. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Seal, Tom (1992). "Roots of Conflict: The First World War and the Political Fragmentation of the Middle East". Naval War College Review. 45 (2): 69–79. ISSN 0028-1484. JSTOR 44638065. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Aytürk, İlker (2010). "Revisiting the language factor in Zionism: The Hebrew Language Council from 1904 to 1914". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 73 (1): 45–64. doi:10.1017/S0041977X09990346. hdl:11693/38150. ISSN 0041-977X. JSTOR 25702989. S2CID 146347123. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Rabin, Chaim (1963). "The Revival of Hebrew as a Spoken Language". The Journal of Educational Sociology. 36 (8): 388–392. doi:10.2307/2264510. ISSN 0885-3525. JSTOR 2264510. Archived from the original on 2023-03-16. Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- ^ Gubbay, Lucien (2000). "The Rise, Decline and Attempted Regeneration of the Jews of the Ottoman Empire". European Judaism: A Journal for the New Europe. 33 (1): 59–69. doi:10.3167/ej.2000.330110. ISSN 0014-3006. JSTOR 41431056. Archived from the original on 2023-05-02. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ de Somogyi, Joseph (1933). "A Qaṣīda on the Destruction of Baghdād by the Mongols". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 7 (1): 41–48. ISSN 1356-1898. JSTOR 607602. Archived from the original on 2023-05-01. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Rabie, Hassanein (1978). "Political Relations Between the Safavids of Persia and the Mamluks of Egypt and Syria in the Early Sixteenth Century". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 15: 75–81. doi:10.2307/40000132. ISSN 0065-9991. JSTOR 40000132.

- ^ "World Jewish Congress".

- ^ Yehuda, Zvi (2017-08-28). The New Babylonian Diaspora. BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789004354012. ISBN 978-90-04-35401-2.

- ^ "Judaism in Syria". rpl.hds.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 2023-05-02. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "Central Synagogue, Aleppo, Syria | Archive | Diarna.org". archive.diarna.org. Archived from the original on 2023-05-02. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "Damascus Jewish History Tour". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Archived from the original on 2023-03-28. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ Naar, Devin E. (2016). "The "Mother of Israel" or the "Sephardi Metropolis"? Sephardim, Ashkenazim, and Romaniotes in Salonica". Jewish Social Studies. 22 (1): 81–129. doi:10.2979/jewisocistud.22.1.03. ISSN 0021-6704. JSTOR 10.2979/jewisocistud.22.1.03.

- ^ Naar, Devin (2016-09-07). Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1-5036-0008-9.

- ^ Naar, Devin E. (2007). "From the "Jerusalem of the Balkans" to the Goldene Medina: Jewish Immigration from Salonika to the United States". American Jewish History. 93 (4): 435–473. ISSN 0164-0178. JSTOR 23887597. Archived from the original on 2023-04-08. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Naar, Devin E. (2014). "Fashioning the "Mother of Israel": The Ottoman Jewish Historical Narrative and the Image of Jewish Salonica". Jewish History. 28 (3/4): 337–372. doi:10.1007/s10835-014-9216-z. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 24709820. S2CID 254602444. Archived from the original on 2023-05-01. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Harrington, Spencer P. M. (1992). "Travel: Turkey's Sephardic Heritage". Archaeology. 45 (6): 72–75. ISSN 0003-8113. JSTOR 41766319. Archived from the original on 2023-05-02. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Д. Т. Левов. Лоза, Свобода, ВИ/786, Софиja, 13. 04 1892, 3.

- ^ †Лоза#, месечно списание, издава Младата македонска книжевна дружина, Свобода, VI/774, Софија, 18. 02 1892, 3.

- ^ К.П.Мисирков, „За Македонцките работи“, јубилејно издание, Табернакул, Скопје, 2003

- ^ Gunzburger Makas, Emily; Damljanovic Conley, Tanja, eds. (2009). Capital Cities in the Aftermath of Empires: Planning in Central and Southeastern Europe. Routledge. p. 7. ISBN 9781135167257.

- ^ Bugajski, Janusz (2016). "Serbia". Ethnic Politics in Eastern Europe: A Guide to Nationality Policies, Organizations and Parties: A Guide to Nationality Policies, Organizations and Parties. Routledge. ISBN 9781315287430.

- ^ a b c Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans: Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 9780521252492.

- ^ Amedoski, Dragana, ed. (2018). Belgrade 1521-1867. Istorijski institut. p. 297. ISBN 9788677431327.

- ^ "The Feudal System".

- ^ "MWNF - Sharing History".

- ^ Belgrade 1521-1867 (Full Text).

- ^ Sotirović, Vladislav B. (2011). "The Serbian Patriarchate of Peć in the Ottoman Empire: The First Phase (1557–94)". Serbian Studies: Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies. 25 (2): 143–169. doi:10.1353/ser.2011.0038. ISSN 1941-9511.

- ^ "Turkish Society (Turkish organization) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on 2008-01-23. Retrieved 2008-03-22. (1912)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kanner, Efi (2016). "Transcultural Encounters: Discourses on Women's Rights and Feminist Interventions in the Ottoman Empire, Greece, and Turkey from the Mid-Nineteenth Century to the Interwar Period". Journal of Women's History. 28 (3): 66–92. doi:10.1353/jowh.2016.0025. ISSN 1527-2036. S2CID 151764981. Archived from the original on 2018-06-02. Retrieved 2022-05-17.

- ^ "Beyond the harem: Ways to be a woman during the Ottoman Empire". 12 August 2016.

- ^ "The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire | Department of Near Eastern Studies".

- ^ "Ottoman Women".

- ^ a b c Tucker, Judith E. (1996). "Revisiting Reform: Women and the Ottoman Law of Family Rights, 1917". The Arab Studies Journal. 4 (2): 4–17. ISSN 1083-4753. JSTOR 27933698. Archived from the original on 2022-04-15. Retrieved 2022-05-17.

- ^ a b Zachs, Fruma; Ben-Bassat, Yuval (2015). "Women's Visibility in Petitions from Greater Syria During the Late Ottoman Period". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 47 (4): 765–781. doi:10.1017/S0020743815000975. ISSN 0020-7438. JSTOR 43998040. S2CID 164613190. Archived from the original on 2022-12-20. Retrieved 2022-05-17.

Sources

- Karpat, Kemal H. (2002). Studies on Ottoman Social and Political History: Selected Articles and Essays. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-12101-3.

- Karpat, K.H., 1973. An inquiry into the social foundations of nationalism in the Ottoman state: From social estates to classes, from millets to nations (No. 39). Center of International Studies, Princeton University.

- Karpat, K.H., 1972. The transformation of the Ottoman State, 1789–1908. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 3(3), pp. 243–281.

- Mazower, Mark (2000). The Balkans: A Short History. Modern Library Chronicles. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-64087-8.

- Stojanović, Mihailo D. (1968) [1939]. The Great Powers and the Balkans, 1875-1878. Cambridge University Press.

- Mete Tunçay; Erik Jan Zürcher (1994). Socialism and nationalism in the Ottoman Empire, 1876-1923. British Academic Press in association with the International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam. ISBN 978-1-85043-787-1.

- William W. Haddad; William Ochsenwald (1977). Nationalism in a non-national state: the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8142-0191-6.

- Charles Jelavich; Barbara Jelavich (20 September 2012). The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804-1920. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80360-9.

- Zeine, Z.N., 1958. Arab-Turkish Relations and the Emergence of Arab Nationalism. Khayat's.

- Kanner, Efi (2016). "Transcultural Encounters: Discourses on Women's Rights and Feminist Interventions in the Ottoman Empire, Greece, and Turkey from the Mid-Nineteenth Century to the Interwar Period". Journal of Women's History. 28 (3): pp. 66–92.

- Kayali, H., 1997. Arabs and Young Turks: Ottomanism, Arabism, and Islamism in the Ottoman Empire, 1908–1918. Univ of California Press.

- Haddad, W.W., 1977. Nationalism in the Ottoman Empire. Nationalism in a Non-national State: the Dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, pp. 3–25.

- Roudometof, V., 1998. From Rum Millet to Greek Nation: Enlightenment, Secularization, and National Identity in Ottoman Balkan Society, 1453–1821. Journal of Modern Greek Studies, 16(1), pp. 11–48.

- Ülker, E., 2005. Contextualising ‘Turkification’: nation‐building in the late Ottoman Empire, 1908–18. Nations and Nationalism, 11(4), pp. 613–636.

- Sućeska, Avdo (1985). Istorija države i prava naroda SFRJ [History of the state and the rights of the people of SFRY]. Sarajevo: Svjetlost. OCLC 442530093.

- Sugar, P.F., 1997. Nationality and society in Habsburg and Ottoman Europe (Vol. 566). Variorum Publishing.

- Cagaptay, Soner (1 February 2014). The Rise of Turkey: The Twenty-First Century's First Muslim Power. Potomac Books, Inc. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-1-61234-650-2.

- Tucker, Judith E. (1996). "Revisiting Reform: Women and the Ottoman Law of Family Rights, 1917". The Arab Studies Journal. 4 (2), pp. 4–17.

- Zachs, Fruma; Ben-Bassat, Yuval (2015). "Womens Visibility in Petitions From Greater Syria During the Late Ottoman Period". International journal of Middle East Studies, 47, pp. 765–781.

- Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian National Awakening 1878-1912. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, pp. 3–88.

- Benbrahim, Hamza. 2023. “Feudal Hierarchy.” Medium. December 16, 2023.

- Khalidi, Rashid, Lisa Anderson, Muhammad Muslih, and Reeva Simon. n.d. “The Origins of Arab Nationalism.”

- “Kurbash - Encyclopedia.” n.d.

- Amedoski, Dragana, and Selim Aslantaş. n.d. Belgrade 1521-1867

- “The Feudal System.” 2023.

- MWNF. "Milos Obrenovic." Sharing History.

- “Beyond the Harem: Ways to Be a Woman during the Ottoman Empire.” 2016. University of Cambridge. August 12, 2016.

- Oxford Bibliographies. “Ottoman Women.”

- Department of near Eastern Studies. “The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire."

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !