Piper J-3 Cub

| J-3 Cub | |

|---|---|

A former-military L-4H Grasshopper in 1990 | |

| General information | |

| Type | Trainer/light aircraft |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Piper Aircraft |

| Designer | |

| Number built | 19,888 (US built)[1] 150 (Canadian-built)[1] 253 TG-8 gliders[1] |

| History | |

| Manufactured | 1938–1947 |

| First flight | 1938 |

| Developed from | Taylor Cub Taylor J-2 |

| Variants | PA-11 Cub Special PA-15 Vagabond PA-16 Clipper PA-18 Super Cub |

The Piper J-3 Cub is an American light aircraft that was built between 1938 and 1947 by Piper Aircraft. The aircraft has a simple, lightweight design which gives it good low-speed handling properties and short-field performance. The Cub is Piper Aircraft's second most-produced model after the PA-28 Cherokee series (>32,000 produced) with over 20,000 built in the United States. Its simplicity, affordability and popularity invokes comparisons to the Ford Model T automobile.

The aircraft is a high-wing, strut-braced monoplane with a large-area rectangular wing. It is most often powered by an air-cooled, flat-4 piston engine driving a fixed-pitch propeller. Its fuselage is a welded steel frame covered in fabric, seating two people in tandem.

The Cub was designed as a trainer. It had great popularity in this role and as a general aviation aircraft. Due to its performance, it was well suited for a variety of military uses such as reconnaissance, liaison and ground control. It was produced in large numbers during World War II as the L-4 Grasshopper. Many Cubs are still flying today. Cubs are highly prized as bush aircraft.

The aircraft's standard chrome yellow paint came to be known as "Cub Yellow" or "Lock Haven Yellow".[2]

Design and development

The Taylor E-2 Cub first appeared in 1930, built by Taylor Aircraft in Bradford, Pennsylvania. Sponsored by William T. Piper, a Bradford industrialist and investor, the affordable E-2 was meant to encourage greater interest in aviation. Later in 1930, the company went bankrupt, with Piper buying the assets, but keeping founder C. Gilbert Taylor on as president. In 1936, an earlier Cub was altered by employee Walter Jamouneau to become the J-2 while Taylor was on sick leave. Some believed the "J" stood for Jamouneau, while aviation historian Peter Bowers concluded the letter simply followed the E, F, G and H models, with the letter "I" skipped because it could be mistaken for the numeral "1".[3][4] When he saw the redesign, Taylor was so incensed that he fired Jamouneau. Piper, however, had encouraged Jamouneau's changes and hired him back. Piper then bought Taylor's share in the company, paying him $250 per month for three years. [5]

Although sales were initially slow, about 1,200 J-2s were produced before a fire in the Piper factory, a former silk mill in Bradford, Pennsylvania, ended its production in 1938. After Piper moved his company from Bradford to Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, the J-3, which featured further changes by Jamouneau, replaced the J-2. The changes integrated the vertical fin of the tail into the rear fuselage structure and covered it simultaneously with each of the fuselage's sides, changed the rearmost side window's shape to a smoothly curved half-oval outline and placed a steerable tailwheel at the rear end of the J-2's leaf spring-style tailskid, linked for its steering function to the lower end of the rudder with springs and lightweight chains to either end of a double-ended rudder control horn. Powered by a 40 hp (30 kW) engine, in 1938, it sold for just over $1,000.[6]

Several alternative air-cooled engines, typically flat-fours, powered the J-3 Cubs, designated J3C when using the Continental A series,[7] J3F using the Franklin 4AC,[8] and J3L with the Lycoming O-145.[9] Very few examples, designated J3P, were equipped with Lenape Papoose 3-cylinder radial engines.[10]

The outbreak of hostilities in Europe in 1939, along with the growing realization that the United States might soon be drawn into World War II, resulted in the formation of the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP). The Piper J-3 Cub became the primary trainer aircraft of the CPTP and played an integral role in its success, achieving legendary status. About 75% of all new pilots in the CPTP (from a total of 435,165 graduates) were trained in Cubs. By war's end, 80% of all United States military pilots had received their initial flight training in Piper Cubs.[11]

The need for new pilots created an insatiable appetite for the Cub. In 1940, the year before the United States entered the war, 3,016 Cubs had been built. Wartime demands soon increased that production rate to one Cub being built every 20 minutes.[11]

Flitfire

Prior to the United States entering World War II, J-3s were part of a fund-raising program to support the United Kingdom. Billed as a Flitfire, a Piper Cub J3 bearing Royal Air Force insignia was donated by W. T. Piper and Franklin Motors to the RAF Benevolent Fund to be raffled off. Piper distributors nationwide were encouraged to do the same. On April 29, 1941, all 48 Flitfire aircraft, one for each of the 48 states that made up the country at that time, flew into La Guardia Field for a dedication and fundraising event which included Royal Navy officers from the battleship HMS Malaya, in New York for repairs, as honored guests.[12][13] At least three of the original Flitfires have been restored to their original silver-doped finish.[14]

Operational history

World War II service

Minutes before the 1941 Attack on Pearl Harbor, Machinist Mate 2nd Class Marcus F. Poston, a student pilot, was on a solo flight through K-T Flying Service, piloting a Piper Cub J-3 over the valley of Oahu. Poston was flying just as the Japanese planes began appearing over the island and was subsequently shot down. Poston managed to bail out and parachute to safety. The Piper J-3 Cub was the first American plane to be shot down in World War II.

The Piper Cub quickly became a familiar sight. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt took a flight in a J-3 Cub, posing for a series of publicity photos to help promote the CPTP. Newsreels and newspapers of the era often featured images of wartime leaders, such as Generals Dwight Eisenhower, George Patton and George Marshall, flying around European battlefields in Piper Cubs.

Civilian-owned Cubs joined the war effort as part of the newly formed Civil Air Patrol, patrolling the Eastern Seaboard and Gulf Coast in a constant search for German U-boats and survivors of U-boat attacks.[15][self-published source?][16][17]

Piper developed a military variant ("All we had to do," Bill Jr. is quoted as saying, "was paint the Cub olive drab to produce a military airplane"),[5] variously designated as the O-59 (1941), L-4 (after April 1942) and NE (U.S. Navy). The L-4 Grasshopper was mechanically identical to the J-3 civilian Cub, but was distinguishable by the use of a Plexiglas greenhouse skylight and rear windows for improved visibility, much like the Taylorcraft L-2 and Aeronca L-3 also in use with the US armed forces. It had accommodations for a single passenger in addition to the pilot. When carrying only the pilot, the L-4 had a top speed of 85 mph (137 km/h), a cruise speed of 75 mph (121 km/h), a service ceiling of 12,000 ft (3,658 m), a stall speed of 38 mph (61 km/h), an endurance of three hours,[18] and a range of 225 mi (362 km).[19] Some 5,413 L-4s were produced for U.S. forces, including 250 built for the U.S. Navy under contract as the NE-1 and NE-2.[20][21]

All L-4 models, as well as other tandem-seat light aircraft from Aeronca and Taylorcraft, were collectively nicknamed "Grasshoppers", although any liaison plane, regardless of manufacturer, was often referred to as a 'Cub'. The L-4 was primarily employed in World War II for artillery spotting and training liaison pilots, but short-range reconnaissance, medical evacuation, and courier or supply missions were not uncommon.[11] During the Allied invasion of France in June 1944, the L-4's slow cruising speed and low-level maneuverability made it an ideal observation platform for spotting hidden German guns and armored vehicles waiting in ambush in the hedgerow bocage country south of the invasion beaches. For these and other operations, the pilot generally carried both an observer and 25-pound (11 kg) communications radio, a load that sometimes exceeded the plane's specified gross weight.[18] After the Allied breakout in France, L-4s were occasionally equipped with improvised racks (usually in pairs or quartets) of infantry bazookas for attacking enemy vehicles. The most famous of these unlikely ground attack planes was an L-4 named Rosie the Rocketer, piloted by Maj. Charles "Bazooka Charlie" Carpenter, whose six bazooka rocket launchers were credited with eliminating several tanks and armored cars during its wartime service,[22][23] especially during the Battle of Arracourt. L-4s could also be operated from ships, using the Brodie landing system.

After the war, many L-4s were sold as surplus, but a considerable number were retained in service.[24] L-4s sold as surplus in the U.S. were redesignated as J-3s, but often retained their wartime glazing and paint.[25]

Postwar

An icon of the era and of American general aviation, the J-3 Cub has long been loved by pilots and nonpilots alike, with thousands still in use. Piper sold 19,073 J-3s between 1938 and 1947, the majority of them L-4s and other military variants. After the war, thousands of Grasshoppers were civilian-registered under the designation J-3. Sixty-five pre-war Taylor and Piper Cubs were assembled from parts in Canada (by Cub Aircraft Corporation Ltd.). After the war, 130 J-3C-65 models were manufactured in Hamilton, Ontario. Sixteen L-4B models, (known as the Prospector), were later manufactured. The last J-3 model was assembled from parts at Leavens Bros. Toronto in 1952.[26] J-3 Cubs were also assembled in Denmark[27] and Argentina and by a licensee in Oklahoma.[28]

In the late 1940s, the J-3 was replaced by the Piper PA-11 Cub Special (1,500 produced), the first Piper Cub version to have a fully enclosed cowling for its powerplant and then the Piper PA-18 Super Cub, which Piper produced until 1981 when it sold the rights to WTA Inc. In all, Piper produced 2,650 Super Cubs. The Super Cub had a 150 hp (110 kW) engine which increased its top speed to 130 mph (210 km/h). Its range was 460 miles (740 km).

Korean War service

On 26 June 1950, one day after the Korean War broke out, the Republic of Korea Air Force flew L-4s to Dongducheon to support the ROK 7th Infantry Division against North Korean military by dropping two bombs from an observer in the rear seat. A total of 70 bombs were dropped until the following day, then aircraft were switched back to reconnaissance mission as bombs were depleted. South Korea lost 25 L-4s throughout the Korean War.[29]

The United States Army also operated small numbers of L-4s, but were replaced by L-16 during the war.[29] The L-4 was in service in many of the same roles it had performed during World War II, such as artillery spotting, forward air control and reconnaissance.[24] Some L-4s were fitted with a high-back canopy to carry a single stretcher for medical evacuation of wounded soldiers.[24]

Modern production

Modernized and up-engined versions are produced by Cub Crafters of Washington and by American Legend Aircraft in Texas, as the Cub continues to be sought after by bush pilots for its short takeoff and landing (STOL) capabilities, as well as by recreational pilots for its nostalgia appeal. The new aircraft are actually modeled on the PA-11, though the Legend company does sell an open-cowl version with the cylinder heads exposed, like the J-3 Cub. An electrical system is standard from both manufacturers.[citation needed]

The J-3 is distinguished from its successors by having a cowl that exposes its engine's cylinder heads — the exposed cylinders of any J-3's engine were usually fitted with sheet metal "eyebrow" air scoops to direct air over the cylinder's fins for more effective engine cooling in flight. Very few other examples exist of "flat" aircraft engine installations (as opposed to radial engines) in which the cylinder heads are exposed. From the PA-11 on through the present Super Cub models, the cowling surrounds the cylinder heads.[30]

A curiosity of the J-3 is that when it is flown solo, the lone pilot normally occupies the rear seat for proper balance, to balance the fuel tank located at the firewall. Starting with the PA-11, as well as some L-4s, fuel was carried in wing tanks, allowing the pilot to fly solo from the front seat.[30]

Variants

Civil

- J-3

- Equipped with a Continental A-40, A-40-2, or A-40-3 engine of 37 hp (28 kW), or A-40-4 engine of 40 hp (30 kW)[31]

- J3C-40

- Certified 14 July 1938 and equipped with a Continental A-40-4 or A-40-5 of 40 hp (30 kW)[7]

- J3C-50

- Certified 14 July 1938 and equipped with a Continental A-50-1 or A-50-2 to -9 (inclusive) of 50 hp (37 kW)[7]

- J3C-50S

- Certified 14 July 1938 and equipped with a Continental A-50-1 or A-50-2 to -9 (inclusive) of 50 hp (37 kW), equipped with optional float kit[7]

- J3C-65

- Certified 6 July 1939 and equipped with a Continental A-65-1 or A-65-3, 6, 7, 8, 8F, 9 or 14 of 65 hp (48 kW) or an A-65-14, Continental A-75-8, A-75-8-9 or A-75-12 of 75 hp (56 kW) or Continental C-85-8 or C-85-12 of 85 hp (63 kW) or Continental C-90-8F of 90 hp (67 kW)[7]

- J3C-65S

- Certified 27 May 1940 and equipped with a Continental A-65-1 or A-65-3, 6, 7, 8, 8F, 9 or 14 of 65 hp (48 kW) or an A-65-14, Continental A-75-8, A-75-8-9 or A-75-12 of 75 hp (56 kW) or Continental C-85-8 or C-85-12 of 85 hp (63 kW) or Continental C-90-8F of 90 hp (67 kW), equipped with optional float kit[7]

- J3F-50

- Certified 14 July 1938 and equipped with a Franklin 4AC-150 Series 50 of 50 hp (37 kW)[8]

- J3F-50S

- Certified 14 July 1938 and equipped with a Franklin 4AC-150 Series 50 of 50 hp (37 kW), equipped with optional float kit[8]

- J3F-60

- Certified 13 April 1940 and equipped with a Franklin 4AC-150 Series A of 65 hp (48 kW) or a Franklin 4AC-171 of 60 hp (45 kW)[8]

- J3F-60S

- Certified 31 May 1940 and equipped with a Franklin 4AC-150 Series A of 65 hp (48 kW) or a Franklin 4AC-171 of 60 hp (45 kW), equipped with optional float kit[8]

- J3F-65

- Certified 7 August 1940 and equipped with a Franklin 4AC-176-B2 or a Franklin 4AC-176-BA2 of 65 hp (48 kW)[8]

- J3F-65S

- Certified 4 January 1943 and equipped with a Franklin 4AC-176-B2 or a Franklin 4AC-176-BA2 of 65 hp (48 kW), equipped with optional float kit[8]

- J3L

- Certified 17 September 1938 and equipped with a Lycoming O-145-A1 of 50 hp (37 kW) or a Lycoming O-145-A2 or A3 of 55 hp (41 kW)[9]

- J3L-S

- Certified 2 May 1939 and equipped with a Lycoming O-145-A1 of 50 hp (37 kW) or a Lycoming O-145-A2 or A3 of 55 hp (41 kW), equipped with optional float kit[9]

- J3L-65

- Certified 27 May 1940 and equipped with a Lycoming O-145-B1, B2, or B3 of 65 hp (48 kW)[9]

- J3L-65S

- Certified 27 May 1940 and equipped with a Lycoming O-145-B1, B2, or B3 of 65 hp (48 kW), equipped with optional float kit[9]

- J3P

- Variant powered by a 50 hp (37 kW) Lenape LM-3-50 or Lenape AR-3-160 three-cylinder radial engine[1][10]

- J-3R

- Variant with slotted flaps powered by a 65 hp (48 kW) Lenape LM-3-65 engine.[1]

- J-3X

- 1944 variant with cantilever wing powered by a 65 hp (48 kW) Continental A-65-8 engine.[1]

- L-4B Prospector

- Canadian manufactured model, with removable rear seat and control, additional capacity, optional extra fuel tank and painted in a PA-12 color scheme.[32]

- Cammandre 1

- A French conversion of J-3 Cub/L-4 aircraft[33]

- Poullin J.5A

- Five L-4 Cubs converted by Jean Poullin for specialist tasks.[34]

- Poullin J.5B

- A single L-4 Cub converted by Jean Poullin for specialist tasks[34]

- Wagner Twin Cub

- A twin fuselage conversion of the J-3[35]

Military

- YO-59

- Four US Army Air Corps test and evaluation J3C-65[36]

- O-59

- Production version for the USAAC; 140 built later redesignated L-4[36]

- O-59A

- Improved version, powered by a 65-hp (48-kW) Continental O-170-3 piston engine; 948 built, later redesignated L-4A[36]

- L-4

- Redesignated YO-59 and O-59[37]

- L-4A

- Redesignated O-59A.[37]

- L-4B

- As per L-4A, but without radio equipment; 980 built[37]

- L-4C

- Eight impressed J3L-65s, first two originally designated UC-83A[37]

- L-4D

- Five impressed J3F-65s[37]

- L-4H

- As per L-4B but with improved equipment and fixed-pitch propeller, 1801 built[37]

- L-4J

- L-4H with controllable-pitch propeller, 1680 built[37]

- UC-83A

- Two impressed J3L-65s, later redesignated L-4C[38]

- TG-8

- Three-seat training glider variant, 250 built[39]

- LNP

- United States Navy designation for three TG-8s received.[39]

- NE-1

- United States Navy designation for dual-control version of J3C-65, 230 built[40]

- NE-2

- As per NE-1 with minor equipment changes, 20 built[40]

Operators

Civil

The aircraft has been popular with flying schools — especially from the pre-World War II existence of the Civilian Pilot Training Program using them in the United States — and remains so with private individuals, into the 21st century.

Military

- Republic of Korea Air Force: Received 10 L-4s from the Army to create the Air Force in 1 October 1949. 8 L-4s were operational at the beginning of the Korean War. Lost 25 vehicles during the war.[29][43]

- Military of Paraguay - L-4[44]

- United States Air Force[1]

- United States Army[43]

- United States Army Air Forces[1]

- United States Navy[1][43]

- Civil Air Patrol

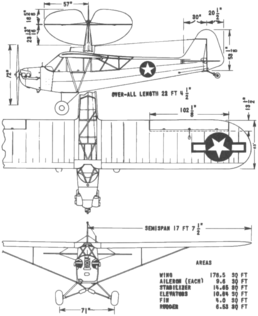

Specifications (J3C-65 Cub)

Data from The Piper Cub Story[47]

General characteristics

- Crew: one pilot

- Capacity: one passenger

- Useful load: 455 lb (205 kg)

- Length: 22 ft 5 in (6.83 m)

- Wingspan: 35 ft 3 in (10.74 m)

- Height: 6 ft 8 in (2.03 m)

- Wing area: 178.5 sq ft (16.58 m2)

- Empty weight: 765 lb (345 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 1,220 lb (550 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Continental A-65-8 air-cooled horizontally opposed four cylinder, 65 hp (48 kW) at 2,350 rpm

Performance

- Maximum speed: 76 kn (87 mph, 140 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 65 kn (75 mph, 121 km/h)

- Stall speed: 33 kn (38 mph, 61 km/h)

- Range: 191 nmi (220 mi, 354 km)

- Service ceiling: 11,500 ft (3,500 m)

- Rate of climb: 450 ft/min (2.3 m/s)

- Wing loading: 6.84 lb/sq ft (33.4 kg/m2)

- Power/mass: 18.75 lb/hp (11.35 kg/kW)

See also

Related development

- American Legend AL3C-100

- CubCrafters CC11-100 Sport Cub S2

- LIPNUR Belalang

- Marawing 1-L Malamut

- Piper J-2

- Piper PA-15 Vagabond

- Piper PA-16 Clipper

- Piper PA-18 Super Cub

- Piper PA-20 Pacer

- Wag-Aero CUBy

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Aeronca Champion

- Aeronca L-3

- American Eagle Eaglet

- Fieseler Fi 156 Storch

- Kitfox Model 5

- Taylorcraft BC-65

- Taylorcraft L-2

Related lists

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Peperell 1987, pp. 22–34

- ^ Lord, Magnus (April 2008). "The story of Cub Yellow". Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- ^ "Piper J-3". Aircraft of the Smithsonian. Archived from the original on March 3, 2006. Retrieved April 2, 2006.

- ^ Peter M. Bowers, Piper Cubs (Tab Books 1993)

- ^ a b Spence, Charles (September 23, 1997). "They're not all Piper Cubs". Aviation History. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

- ^ Piper J-3 Cub Film Series (TM Technologies, footage from 1937–1948 shows step-by-step construction. 110 minutes.)

- ^ a b c d e f Federal Aviation Administration (August 2006). "AIRCRAFT SPECIFICATION NO. A-691" (PDF). Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Federal Aviation Administration (August 2006). "AIRCRAFT SPECIFICATION NO. A-692" (PDF). Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Federal Aviation Administration (August 2006). "AIRCRAFT SPECIFICATION A-698" (PDF). Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ a b Federal Aviation Administration (October 1942). "Approved Type Certificate 695" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2010. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ^ a b c Guillemette, Roger. "The Piper Cub". US Centennial of Flight Commission. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved April 2, 2006.

- ^ "Shindig at N.Y. Airport Opens Fund Drive for R.A.F". Life. May 12, 1941. p. 36.

- ^ "Alamo Liaison Squadron". Archived from the original on November 10, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ^ "Museum Guide". North Carolina Aviation Museum.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Campbell, Douglas E., "Volume III: U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Coast Guard Aircraft Lost During World War II Listed by Aircraft Type", Lulu.com, ISBN 978-1-257-90689-5 (2011), p. 374[self-published source]

- ^ "Civil Air Patrol". Air Force Link. November 27, 2006. Archived from the original on March 15, 2008.

- ^ Ames, Drew (April 2007). "Guarding the home skies". America in WWII. 310 Publishing. ISSN 1554-5296. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- ^ a b Fountain, Paul, The Maytag Messerschmitts, Flying Magazine, March 1945, p. 90: With one pilot aboard, the L-4 had a maximum endurance of three hours' flight time (no reserve) at a reduced cruising speed of 65 mph.

- ^ Gunston, Bill and Bridgman, Leonard, Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II, Studio Editions, ISBN 978-1-85170-199-5 (1989), p. 253

- ^ Frédriksen, John C., Warbirds: An Illustrated guide to U.S. Military Aircraft, 1915–2000, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-131-1 (1999), p. 270

- ^ Bishop, Chris, The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II, Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., ISBN 978-1-58663-762-0 (2002), p. 431

- ^ What's New in Aviation: Piper Cub Tank Buster, Popular Science, Vol. 146 No. 2 (February 1945) p. 84

- ^ Kerns, Raymond C., Above the Thunder: Reminiscences of a Field Artillery Pilot in World War II, Kent State University Press, ISBN 978-0-87338-980-8 (2009), pp. 23–24, 293–294

- ^ a b c Edwards, Paul M., Korean War Almanac, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-6037-5 (2006), p. 502

- ^ Nicholas Aircraft Sales, Flying Magazine, April 1946, Vol. 38, No. 4, ISSN 0015-4806, p. 106

- ^ Price, Cameron. "Cub Aircraft History". Toronto Aviation History. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ Nikolajsen, Ole. "Cub Aircraft Co. Ltd. i Lundtofte 1937 - 1940" (PDF). Ole-Nikolajsen.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 4, 2023. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ Ford, Daniel. "Cub Production, 1931-2019". The Piper Cub Forum. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c Bak, Dongchan (March 2021). Korean War : Weapons of the United Nations (PDF) (in Korean). Republic of Korea: Ministry of Defense Institute for Military History. pp. 463–466. ISBN 979-11-5598-079-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 20, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ a b Clark, Anders. (21 November 2014) "Piper J-3 Cub: The World's Most Iconic Airplane". Disciples of Flight. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Federal Aviation Administration (October 1939). "Approved Type Certificate 660" (PDF). Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ Price, Cameron. "Cub Aircraft History". Toronto Aviation History. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ "Cammandre 1". Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Gaillard, Pierre (1990). Les Avions Francais de 1944 a 1964 (in French). Paris: Editions EPA. ISBN 2-85120-350-9.

- ^ "TwinNavion.com". www.twinnavion.com. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- ^ a b c Andrade 1979, p. 140

- ^ a b c d e f g Andrade 1979, p. 129

- ^ Andrade 1979, p. 81

- ^ a b Andrade 1979, p. 170

- ^ a b Andrade 1979, p. 201

- ^ Heyman, Jos (November 2005). "Indonesian aviation 1945-1950" (PDF). adf-serials.com. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 14, 2005.

- ^ Heyman (2005), pp. 19, 22.

- ^ a b c Triggs, James M.: The Piper Cub Story, pages 13–19. The Sports Car Press, 1963. SBN 87112-006-2

- ^ Krivinyi, Nikolaus: World Military Aviation, page 181. Arco Publishing Company, 1977. ISBN 0-668-04348-2

- ^ World Air Forces – Historical Listings Thailand (THL), archived from the original on January 25, 2012, retrieved August 30, 2012

- ^ Andrade 1979, p. 239

- ^ Triggs, James M.: The Piper Cub Story, page 31. The Sports Car Press, 1963. SBN 87112-006-2

Bibliography

- Andrade, John (1979). U.S.Military Aircraft Designations and Serials since 1909. Midland Counties Publications. ISBN 0-904597-22-9.

- Bowers, Peter M. (1993). Piper Cubs. McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8306-2170-9.

- Peperell, Roger W; Smith, Colin M (1987). Piper Aircraft and their Forerunners. Tonbridge, Kent, England: Air-Britain. ISBN 0-85130-149-5.

- Gaillard, Pierre (1990). Les Avions Francais de 1944 a 1964 (in French). Paris: Editions EPA. ISBN 2-85120-350-9.

- Neto, Ricardo Bonalume (March–April 1999). "'Ugly Ducklings' and the 'Forgotten Division': Brazilian Piper L-4s in Italy, 1944–1945, Part One". Air Enthusiast (80): 36–40. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Neto, Ricardo Bonalume (May–June 1999). "'Ugly Ducklings' and the 'Forgotten Division': Brazilian Piper L-4s in Italy, 1944–1945, Part Two". Air Enthusiast (81): 73–77. ISSN 0143-5450.

- "Pentagon Over the Islands: The Thirty-Year History of Indonesian Military Aviation". Air Enthusiast Quarterly (2): 154–162. n.d. ISSN 0143-5450.

External links

- Fiddler's Green - history of the J-3

- Piper Aircraft, Inc. - History - Brief timeline of the history of Piper Aircraft, starting with the Piper Cub

- Sentimental Journey - Annual fly-in of Piper Cubs held in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !