1998 bombing of Iraq

| Operation Desert Fox | |

|---|---|

| Part of the prelude to the Iraq War | |

A Tomahawk cruise missile is fired from an Arleigh Burke-class destroyer during Operation Desert Fox in December 1998 | |

| Location | |

| Commanded by | |

| Date | 16–19 December 1998 |

| Executed by | United States Armed Forces |

| Outcome | Coalition military success[1] Politically inconclusive[1]

|

| Casualties |

|

The 1998 bombing of Iraq (code-named Operation Desert Fox) was a major bombing campaign against Iraqi targets, from 16 to 19 December 1998, by the United States and the United Kingdom. On 16 December 1998 Bill Clinton announced that he had ordered strikes against Iraq. The strikes were launched due to Iraq's failure to comply with United Nations Security Council resolutions and its interference with United Nations inspectors that were searching for potential weapons of mass destruction. The inspectors had been sent to Iraq in 1997 and were repeatedly refused access to certain sites.

The operation was a major flare-up in the Iraq disarmament crisis as it involved a direct attack on Iraq. The aim of the bombing was to disable military and security targets which may have enabled Iraq to produce, store, maintain, and deliver weapons of mass destruction. The bombing campaign had been anticipated earlier in the year and faced criticism both in the U.S. and from members of the international community.[2] Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates initially announced they would deny the U.S. military the use of local bases for the purpose of air strikes against Iraq.[3]

The bombing was criticized by Clinton's detractors, who accused him of using the bombing to direct attention away from the ongoing impeachment proceedings he was facing.

Background

U.S. President Bill Clinton had been working under a regional security framework of dual containment, which involved utilizing military force when Iraq challenged the United States or the international community.

Although there was no Authorization for Use of Military Force, Clinton signed the Iraq Liberation Act into law on 31 October 1998.[4][5] The new act appropriated funds for Iraqi opposition groups with the goal of carrying out a regime change.

Prior to Desert Fox, the U.S. almost led a bombing campaign against Saddam called Operation Desert Thunder. It was abandoned at the last minute when Iraq allowed the United Nations to continue weapons inspections.[6]

Degrading WMD capabilities

Clinton administration officials stated that the aim of the mission was to degrade Iraq's ability to manufacture and use weapons of mass destruction, not to eliminate it. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, when questioned about the distinction between degradation and elimination, commented that the operation did not strive to eliminate Iraqi weapons of mass destruction, but instead to make their use and production more difficult and less reliable.[7]

The main targets of the bombing included weapons research and development installations, air defense systems, weapon and supply depots, and the barracks and command headquarters of Saddam's elite Republican Guard. Iraqi air defense batteries, unable to target the American and British jets, began to blanket the sky with near random bursts of flak fire however the air strikes continued, and cruise missile barrages launched by naval vessels began being used in addition to bombs dropped by planes. By the night of the fourth day of the operation most of the specified targets had been damaged or destroyed and the operation was deemed a success.

Military operations

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2010) |

U.S. Navy aircraft from Carrier Air Wing Three, flying from the USS Enterprise, and Patrol Squadron Four flew combat missions from the Persian Gulf in support of ODF. The operation marked the first time that women flew combat sorties as U.S. Navy strike fighter pilots[8][9] and the first combat use of the United States Air Force's B-1B bomber. Ground units included the (), of which 2nd Battalion 4th Marines served as the ground combat element. The U.S. Air Force sent several sorties of F-16s and A-10s from Ahmad al-Jaber Air Base into Iraq to fly night missions in support of the operation.

On the second night of Operation Desert Fox, 12 B-52s took off from the island of Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean and launched a barrage of conventional air-launched cruise missiles (CALCMs). The other bomber wing was the 28th AEG out of Thumrait AB. The missiles successfully struck multiple Iraqi targets, including six of President Saddam Hussein's palaces, several Republican Guard barracks, and the Ministries of Defense and Military Industry. The following evening, two more B-52 crews launched 16 more CALCMs. Over a two-night period, aircrews from the 2nd and 5th Bomb Wings launched a total of 90 CALCMs. The B-1 Lancer bomber made its combat debut by striking at Republican Guard targets. From Thumrait AB, Sultanate Oman. The 28th AEG with the B-1b aircraft from Ellsworth and Dyess AFB also conducted missions. Also on 17 Dec, USAF aircraft based in Kuwait participated, as did British Royal Air Force Tornado aircraft. The British contribution totaled 15 percent of the sorties flown during Desert Fox.[10]

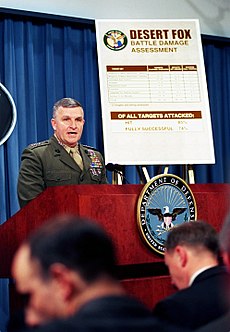

By 19 December, U.S. and British aircraft had struck 97 targets, and Secretary of Defense William Cohen claimed the operation was a success. Supported by Secretary Cohen, as well as United States Central Command commander General Anthony Zinni and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Henry H. Shelton, President Bill Clinton declared "victory" in Operation Desert Fox. In total, the 70-hour campaign saw U.S. forces strike 85 percent of their targets, 75 percent of which were considered "highly effective" strikes. More than 600 sorties were flown by more than 300 combat and support aircraft, and 600 air-dropped munitions were employed, including 90 air-launched cruise missiles and 325 Tomahawk land attack missiles (TLAM). Operation Desert Fox inflicted serious damage to Iraq's missile development program, although its effects on any WMD program were not clear. Nevertheless, Operation Desert Fox was the largest strike against Iraq since the early 1990s Persian Gulf War, until the commencement of Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003. In October 2021, General Zinni gave an upbeat bomb damage assessment of the operation.[11]

97 sites were targeted in the operation with 415 cruise missiles and 600 bombs, including 11 weapons production or storage facilities, 18 security facilities for weapons, 9 military installations, 20 government CCC facilities, 32 surface-to-air missile batteries, 6 airfields, and 1 oil refinery. According to U.S. Defense Department assessments, on 20 December, 10 of these targets were destroyed, 18 severely damaged, 18 moderately damaged, 18 lightly damaged, and 23 not yet assessed. According to the Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister, the allied action resulted in 242 Iraqi military casualties, including 62 killed and 180 wounded. However, on 5 January 1999, American General Harry Shelton told the U.S. Senate that the strikes killed or wounded an estimated 1,400 members of Iraq's Republican Guard.[12] The number of Civilian casualties has been equally disputed. Iraq's former ambassador to the UN, Nizar Hamdoon said in December 1998 that there was thousands of civilians dead and wounded.[13] The international Red Cross reported 40 civilians killed and 80 injured in Baghdad.[14]

Reaction

In reaction to the attack, three of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (Russia, France, and the People's Republic of China) called for the lifting of the eight-year oil embargo on Iraq, the reorganizing or disbanding of the United Nations Special Commission, and the firing of its chairman, Australian diplomat Richard Butler.[15]

Criticism

Accusations of an ulterior motive

Former U.S. Army intelligence analyst William Arkin claimed in his January 1999 column in The Washington Post that the operation was focused on destabilizing the Iraqi government, and that claims of WMDs were being used as an excuse.[citation needed]

According to Department of Defense personnel with whom Arkin spoke, CENTCOM chief Anthony Zinni stated that the U.S. only attacked biological and chemical sites that had been identified with a high degree of certainty, and that the reason for the low number of targets was because intelligence specialists could not identify weapons sites with enough specificity to comply with Zinni's directive.

Dr. Brian Jones was the top intelligence analyst on chemical, biological and nuclear weapons at the Ministry of Defence.[16] He told BBC Panorama in 2004 that Defence Intelligence Staff in Whitehall did not have a high degree of confidence any of the facilities bombed in Operation Desert Fox were active in producing weapons of mass destruction. The testimony given by Jones is supported by the former Deputy Chief of Defence Intelligence, John Morrison, who informed the same program that, before the operation had ended, DIS came under pressure to validate a prepared statement to be delivered by then Prime Minister Tony Blair, declaring the operation an unqualified success. Large-scale damage assessment takes time, responded Morrison, therefore his department declined to sign up to a premature statement. "After Desert Fox, I actually sent a note round to all the analysts involved congratulating them on standing firm in the face of, in some cases, individual pressure to say things that they knew weren't true". Later on, after careful assessment and consideration, Defence Intelligence Staff determined that the bombing had not been all that effective.[17]

The Duelfer Report concluded in 2004 that Iraq's WMD capability "was essentially destroyed in 1991" following the end of sanctions.[18]

Distraction from Clinton impeachment scandal

Some critics of the Clinton administration, including Republican members of Congress, expressed concern over the timing of Operation Desert Fox.[19][20][page needed] The four-day bombing campaign occurred at the same time the U.S. House of Representatives was conducting the impeachment hearing of President Clinton. Clinton was impeached by the House on 19 December, the last day of the bombing campaign. A few months earlier, similar criticism was levelled during Operation Infinite Reach, wherein missile strikes were ordered against suspected terrorist bases in Sudan and Afghanistan on 20 August. The missile strikes began three days after Clinton was called to testify before a grand jury during the Lewinsky scandal and his subsequent nationally televised address later that evening in which Clinton admitted to having an inappropriate relationship.[21]

Criticism of the extent of the operation

Other critics, such as former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, said the attacks did not go far enough, commenting that a short campaign was likely not to make a significant impact.

According to Charles Duelfer, after the bombing, the Iraqi ambassador to the UN told him, "If we had known that was all you would do, we would have ended the inspections long ago."[22]

Gen. Peter de la Billiere, a former head of the SAS who commanded British forces in the 1991 Gulf war, questioned the political impact of the bombing campaign, saying aerial bombardments were not effective in driving people into submission, but tend to make them more defiant.[4]

See also

- January 1993 airstrikes on Iraq

- 1993 cruise missile strikes on Iraq

- 1996 cruise missile strikes on Iraq

References

- ^ a b Boyne, Walter J. (2002). Air Warfare: an International Encyclopedia: A-L. ABC-CLIO. p. 174. ISBN 9781576073452. OL 12237486M.

- ^ "Monday, February 16, 1998". DemocracyNow. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008.

- ^ "Tuesday, February 17, 1998". DemocracyNow. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008.

- ^ a b CURTIS, MARK (17 April 2023). "Blair misled parliament over 1998 Iraq bombing, files show". Declassified Media Ltd. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- ^ "Iraq Liberation Act of 1998". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 11 July 2008.

- ^ "Operation Desert Thunder / Desert Viper". GlobalSecurity.org. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) Archived 15 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine NewsHour Online Web site (for the NewsHour with Jim Lehrer television program on PBS, Web page containing transcript of television interview and titled "Secretary Albright" 17 December 1998, accessed 25 September 2006

- ^ "Military Women in Operation Desert Fox". Userpages.aug.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ "Operation DESERT FOX Briefing with Secretary Cohen and Gen. Zinni, 21 Dec 98". United States Department of Defense. 21 December 1998. Archived from the original on 9 March 2008.

- ^ "Factsheets: Operation Desert Fox". Air Force Historical Studies Office. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ "General Anthony Zinni (Ret.) on Wargaming Iraq, Millennium Challenge, and Competition". Center for International Maritime Security. 18 October 2021. Archived from the original on 22 March 2022.

- ^ Carrington, Anca; Jeffries, Leon M. (2003). Iraq: Issues, Historical Background, Bibliography. Nova Publishers. p. 16. ISBN 9781590332924. OL 8846480M.

- ^ Cordesman, Anthony (26 December 1998). "The Military Effectiveness Of Desert Fox: A Warning About the Limits of the Revolution in Military Affairs and Joint Vision 2010" (PDF).

- ^ LaForge, John M. (2001). "Commentary: U.S.—U.K. War on Iraq: Hypocrisy and Lies". Peace Research. 33 (1): 59–67. ISSN 0008-4697. JSTOR 23607785.

- ^ Gellman, Barton (22 December 1998). "Iraq Inspections, Embargo in Danger at U.N. Council". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008.

- ^ "Dr Brian Jones "confused" by Prime Minister's evidence to Hutton". BBC. 11 July 2004. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012.

- ^ "A failure of intelligence". BBC Panorama. 11 July 2004. Archived from the original on 9 July 2006.

- ^ Duelfer, Charles. "Comprehensive Report of the Special Adviser to the DCI on Iraq's WMD" (PDF). Government Publishing Office. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Conservative Lawmakers Decried Clinton's Attacks Against Osama As 'Wag the Dog'". ThinkProgress. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (1999). No One Left to Lie To. Verso. ISBN 978-1-859-84736-7. OL 6804563M.

- ^ "Clinton's airstrike motives questioned Many wonder if attack was meant to distract from Lewinsky matter". The Baltimore Sun. 23 August 1998. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ Duelfer, Charles (24 February 2012). "In Iraq, done in by the Lewinsky affair". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013.

External links

- Overview of Operation Desert Fox – DefenseLink

- Operation Desert Fox – BBC News

- Transcript of President Clinton's speech announcing the attack – CNN

- Iraq attacked in 'Operation Desert Fox' – CNN

- Strike on Iraq – Operation Desert Fox – CNN

- Operation Desert FoxE: Effectiveness With Unintended Effects

- Operation Desert Fox

- Tony Holmes (2005), US Navy F-14 Tomcat Units of Operation Iraqi Freedom, Osprey Publishing Limited.

- 1998 in international relations

- 1998 in Iraq

- 20th-century Royal Air Force deployments

- Aerial bombing operations and battles

- Airstrikes conducted by the United States

- Attacks on barracks in Iraq

- Aerial operations and battles involving the United Kingdom

- Aerial operations and battles involving the United States

- Clinton administration controversies

- 1998 building bombings

- December 1998 events in Iraq

- Airstrikes during the Iraqi no-fly zones conflict

- Residential building bombings in Iraq

- Iraq and weapons of mass destruction

- Iraq–United Kingdom military relations

- United States Marine Corps in the 20th century

- Attacks on military installations in 1998

- Attacks on airbases in Iraq

- Military operations involving airports

- Airport bombings in Iraq

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !